Rare Elizabethkingia Infections: Report Suggests More Than 1 Source

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

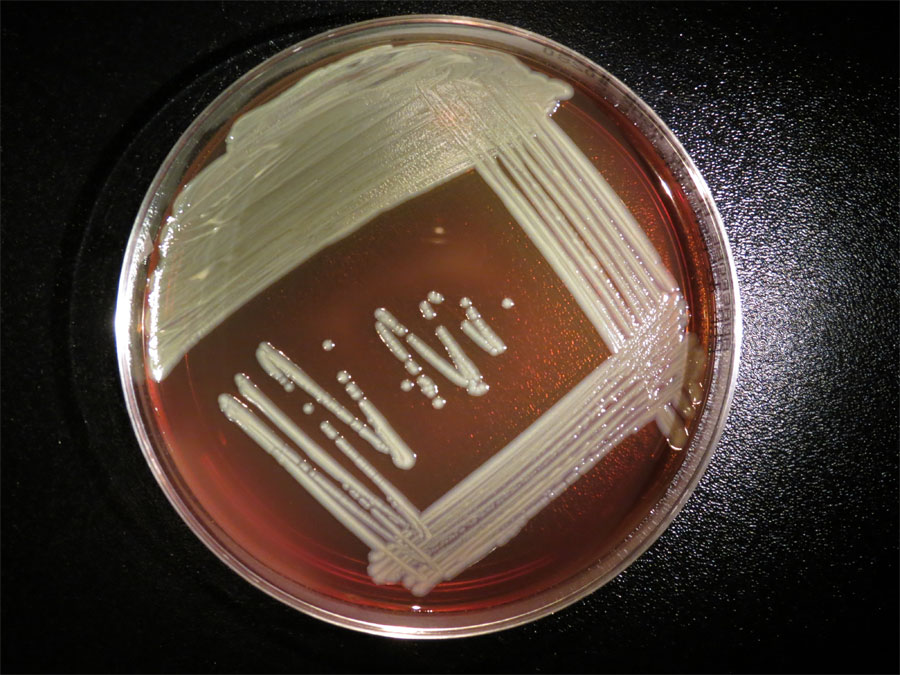

Exactly how 10 people in Illinois recently became infected with a rare bacterial illness called Elizabethkingia is still a mystery, but a new report finds that there were likely multiple sources for the infections.

The Illinois cases came to light after an outbreak of the bacteria sickened nearly 60 people in Wisconsin. To see if there were related cases in Illinois, the state's health department started an investigation, which revealed that at least 10 people in Illinois had been infected with the bacteria Elizabethkingia anophelis between June 2014 and March 2016.

Genetic testing showed that all 10 people were infected with the same strain of Elizabethkingia bacteria, but that this strain was different from the one that was causing illnesses in Wisconsin.

The illnesses in Illinois were highly fatal — seven of the 10 patients died, including six who died within a month of the time that their samples were tested by officials. Most of the patients were elderly and had at least one serious underlying health condition, the new report said. [6 Superbugs to Watch Out For]

All of the patients stayed in a hospital or nursing home during the month leading up to their positive test for Elizabethkingia, and some stayed at multiple hospitals during the course of their illness. In total, the 10 patients were cared for at 19 health care facilities, and most of the time, the patients didn't stay at the same hospital or nursing home as the others, the report said.

What's more, when officials asked the 19 health care facilities to report any cases of Elizabethkingia going back to 2012, they found that, on average, there were a total of 17Elizabethkingia infections per year, and that the average number of reported infections hadn't increased over the years.

This evidence does not support the idea that there was a sudden outbreak with a single source that sickened all the patients, the new report said. "Instead, this more likely represents ongoing sporadic infection among critically ill patients," the report said. [27 Oddest Medical Cases]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition, the researchers found that a previous Illinois outbreak of Elizabethkingia in 2012 to 2013 was also caused by a strain of bacteria that was very similar to the one that sickened the 10 patients in 2014 to 2016. Previously, health officials had thought the 2012 to 2013 outbreak was caused by a different species, called Elizabethkingia meningoseptica, but genetic testing showed that it was actually caused by Elizabethkingia anophelis.

The evidence "does point to distinct infection pathways," rather than a single source, said study researcher Livia Navon, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention career epidemiology field officer at the Illinois Department of Public Health. Navon noted that the cases in the 2014 to 2016 cluster occurred over an extended period of time, and that few patients stayed at the same health care facility.

However, Navon said that much remains to be learned about these bacteria. "This does appear to be an opportunistic pathogen, i.e., affecting those with underlying health conditions/compromised immune systems," Navon told Live Science in an email. But "how individual patients … acquired the infection remains unknown," Navon said.

More research is needed to identify the infection's routes of transmission as well as factors that increase the risk of transmission, Navon said.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus