Brain-Infecting Parasite May Be More Common in NY Than Experts Thought

NEW ORLEANS — Brain infections from a parasite called Taenia solium are more common on Long Island, New York, than experts previously thought, a new study finds.

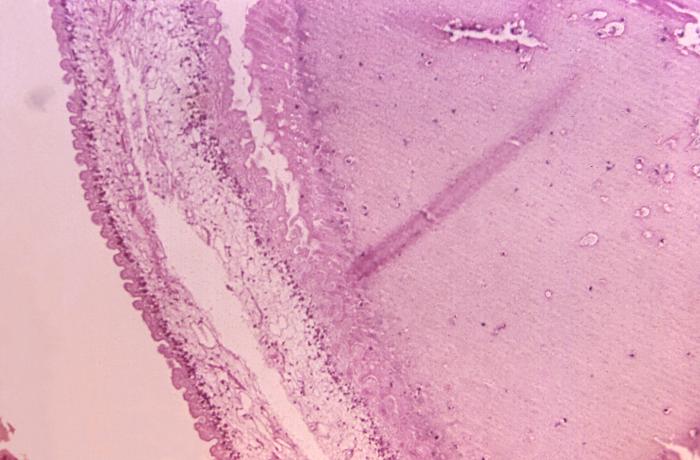

T. solium is found in raw or undercooked pork. If a person eats undercooked pork that contains this parasite in its larval stage, when it has partially developed, a tapeworm can grow in his or her intestine.

For a person's brain to become infected, an additional step is required: The tapeworm in the intestine must lay eggs, which are excreted from the body in a person's feces. People can get an infection called cysticercosis if even tiny amounts of these eggs somehow wind up in their food or water. (This method of transmission called the oral-fecal route, and is common in the spread of parasites and other pathogens.)

These ingested eggs penetrate though the intestinal wall, and then from there they go on to infect the brain, muscle or other tissues in the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). [The 10 Most Diabolical Parasites]

Therefore, people who live in the same house as someone with an intestinal tapeworm have a higher risk of getting cysticercosis than people who don't live with someone with a tapeworm, the CDC says.

People can go years without knowing that they have the infection, said Dr. Amy Spallone, a resident in internal medicine at Stony Brook University Hospital in New York and the lead author of the study.

The parasite may go undetected until the infected person has a seizure, or needs a brain scan for an unrelated issue, Spallone told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After doctors at Stony Brook noticed an increase in the number of patients with this type of brain infection, they decided to investigate how common it was on Long Island, she said.

In the study, the researchers looked at all of the cases of T. solium infections over a 10-year period at their hospital. They found 44 cases between 2005 and 2015, with slightly more cases in males than in females, according to the study, which was presented here Thursday (Oct. 27), at IDWeek 2016, a meeting of several organizations focused on infectious diseases.

The researchers noted that they found that brain infections from T. solium were most common in people living in predominantly Hispanic communities, compared with in other communities. Moreover, the majority of the patients had come to the U.S. after living in Central American countries, where the parasite is found in the environment.

It's not entirely clear how the parasite gets into the brain, Spallone said. Indeed, if a person ingests the parasitic eggs, the infection can turn up anywhere in the body, she said.

When it ends up in the brain, however, the consequences are more severe, Spallone said.

Exactly where the parasite goes in the brain affects how a person responds to the infection, Spallone said. In the majority of the cases that Spallone and her co-authors looked at, the infections were in the brain tissue. In certain locations, the infection may cause seizures, for example. The infection can be deadly in some cases. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

However, in some instances, the parasites were found in the tissue just below the brain, near the brain stem, Spallone said. In these cases, patients can develop severe swelling in their brain, because the parasite can block the circulation of the cerebrospinal fluid, she said. This can lead to a condition called hydrocephalus, which requires surgery.

Anti-parasitic drugs are available to treat the infection, Spallone said. However, diagnosing the disease can sometimes be difficult, she said. For example, many people are diagnosed through a brain scan, but it isn't practical to give brain scans to every patient, she said. And although blood tests are available, they don't always pick up signs of the infection, she said. In some cases, doctors will see a lesion on a brain scan but the blood test will come back negative, she said.

Spallone noted that she was surprised by how prevalent the infection was on Long Island. In the rest of the United States, the prevalence of the disease is not well understood, she said.

The findings have not been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Originally published on Live Science.