Self-Destructing Battery Can Dissolve Itself in 30 Minutes

A new self-destructing battery can power a simple electronic device for up to 15 minutes and then dissolve in water. It could pave the way for so-called transient power sources for scientific instruments or tools of espionage, according to a new study.

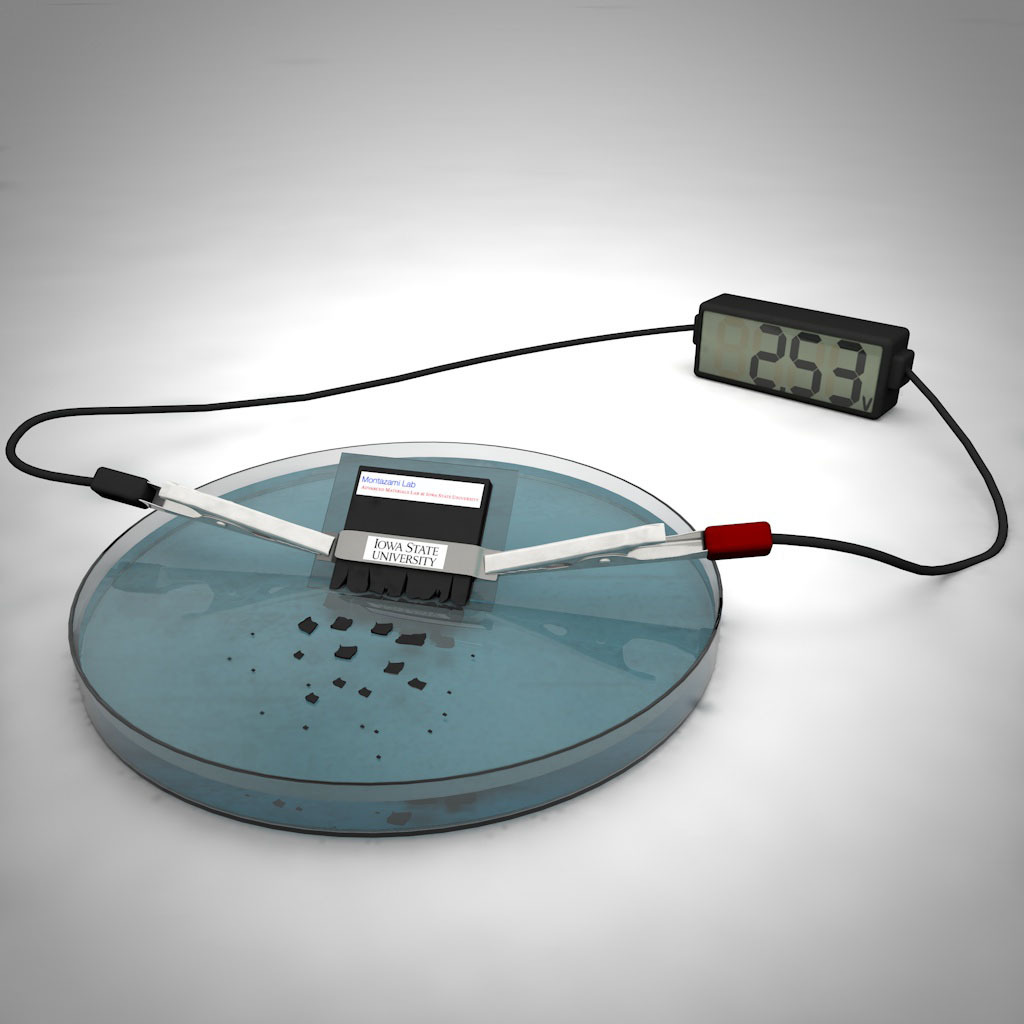

Engineers have developed a novel variety of battery capable of powering a simple electronic device, such as a four-function calculator, and then dissolving in water in half an hour. The new transient battery represents a marked improvement in voltage and disintegration time over its predecessors, the researchers said.

The lithium-ion battery, the first transient battery of its kind, is "very similar to a conventional battery," study co-author Reza Montazami, who heads the Advanced Materials Lab at Iowa State University, told Live Science. [Top 10 Inventions That Changed the World]

The battery's polymer casing, made from a molecule that can form long repeating chains, swells and physically breaks itself and the other components into small pieces when exposed to water, the researchers said. Devices powered by this type of battery could serve their function or transmit data, and then be washed away in the rain.

"Their mechanism relies simply on hydration," Christopher Bettinger, a polymer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh who was not involved with the new study, told Live Science. "That's a unique discovery."

The newly developed battery takes about 30 minutes to dissolve, Montazami said, whereas other transient batteries relying on different chemical processes can take hours or days to break down.

The battery can generate about 2.7 volts, which is similar to the electric potential produced by a pair of conventional AA batteries. This means the new invention can power devices that lower-voltage transient batteries cannot. However, the use of lithium makes the new battery unsuitable for biomedical applications, such as to power implants, Montazami said. Still, the invention could have other medical uses, in addition to being used for surveillance, military or environmental purposes, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because the current battery can power a device for only 15 minutes, its applications right now are limited, Bettinger said, but "it will be interesting to see the limits on capacity, theoretical or practical."

And Montazami said he has other immediate plans. "Our next step is to gain a better understanding of how these batteries break down."

The research was published June 22 in the Journal of Polymer Science, Part B: Polymer Physics.

Original article on Live Science.