Why Some Flies Have Mega Sperm

Picky females have driven the evolution of mega sperm in males as a way to ensure that the gals will get only the best mates, new research finds.

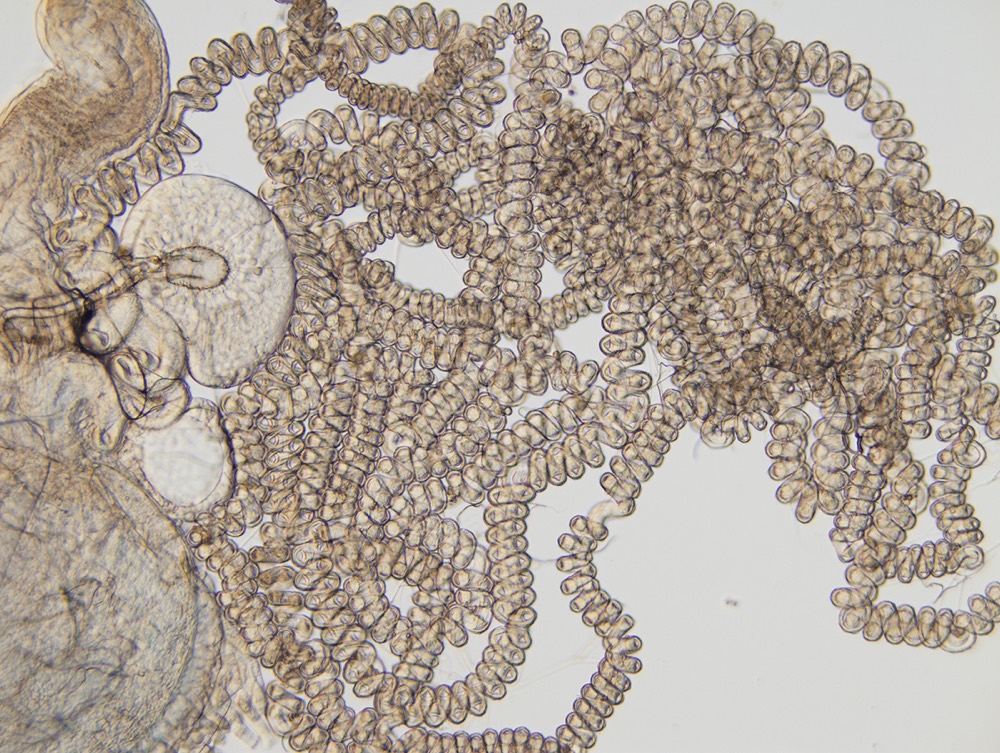

Tiny fruit flies have record-breaking sperm cells. The sperm of Drosophila bifurca can reach lengths of 2.3 inches (5.8 centimeters), for example. Researchers have long known that the peculiarities of the female fruit fly's reproductive tract are responsible for these enormous sperm, which take a huge amount of energy to produce. Female fruit flies have a sperm-storage organ in which they hold sperm from multiple matings. In this organ, the sperm cells jockey for access to an egg in a process of postcopulatory competition.

Now, researchers have found out why this sperm-versus-sperm competition benefits females. Essentially, the need to produce huge sperm pushes low-quality males out of the mating game, leaving only the fittest males for females to choose from. This means giant sperm are similar to heavy antlers or flashy feathers: a costly expenditure to ensure males have a chance to pass on their genes. [In Photos: The World's Oldest Fossilized Sperm]

A sperm paradox

Sperm are the most varied and fastest-evolving cells in the body, said Scott Pitnick, an evolutionary biologist at Syracuse University in New York and an author of the new research, published today (May 25) in the journal Nature. Sperm cells are also unique among body cells in that they spend much of their life span in a foreign environment — the female reproductive tract. But the conditions of the female reproductive tract have been understudied, Pitnick told Live Science.

"If you want to understand all that variation, you have to look at what sperm are doing inside of females," he said.

Sperm competition is a major part of reproduction for many organisms, Pitnick said, but biologists mostly thought of this process as being like a raffle: the more tickets you buy, the more likely you are to win. In that case, males should produce massive amounts of cheap sperm in order to have the best chances of reproduction. [7 Interesting Facts About Sperm]

Giant fruit fly sperm didn't fit that mold at all. These sperm are very expensive to produce; they should also theoretically reduce competition, Pitnick said. Because fruit flies that produce mega sperm can produce only a few sperm cells at a time — as few as six per every egg females produce — this should decrease the number of sperm vying for fertilization and ease the selective pressures driving sperm size upward.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But that wasn't happening. Now, it's clearer why that is the case. Pitnick and his colleagues bred multiple lines of fruit flies with sperm "tagged" by fluorescent proteins, so researchers could tell which sperm came from which flies. In doing so, the researchers were able to determine the factors that influence when and how sperm are successful.

They found that there are strong genetic correlations between the length of the female sperm-storage organ and the length of sperm in a species such that when females evolve longer sperm-storage organs, males automatically produce longer sperm.

Meanwhile, females with longer sperm-storage organs also evolve to mate more frequently, which heightens the sperm war going on in their reproductive tracts. This means that even bigger sperm are likely to win the battle and go on to produce offspring. Only the highest-quality males can keep up in this cycle of sperm competition, so low-quality males get pushed out of the mating game. Females thus get the pick of the litter as far as genetics for their offspring.

Antlers, feathers and … sperm?

The findings explain why competition continues even as there are fewer sperm to compete, Pitnick said.

"As sperm length evolves, you get all this weird self-reinforcement that keeps driving it further and further along," he said.

The findings also reveal that though female fruit flies "choose" sperm simply based on the size of their own storage organs, the process works much like the sexual selection that occurs for flashy male ornamentation such as peacock tails or deer antlers, the researchers said. In fact, the selection is stronger than for many classic sexually selected traits such as lizard horns or the enormous jaws of stag beetles.

The parallel between sexual selection for giant sperm and sexual selection for other traits is useful, Pitnick said, because the mechanism by which females "pick" sperm is simple anatomy, not complex cognition.

"We have a simple physiological basis where you can actually look at the genetics of female choice," he said. "When people think about sex differences, they should be thinking about not just plumage and antlers and courtship dances. They should [also] be thinking about sperm and female reproduction tracts."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.