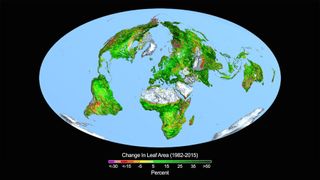

The excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has created a greener planet, a new NASA study shows.

Around the world, areas that were once icebound, barren or sandy are now covered in green foliage. All told, carbon emissions have fueled greening in an area about twice the size of the continental United States between 1982 and 2009, according to the study.

While lush forests and verdant fields may sound like a good thing, the landscape transformation could have long-term, unforeseen consequences, the researchers say.

The radical greening "has the ability to fundamentally change the cycling of water and carbon in the climate system," lead author Zaichun Zhu, a researcher from Peking University in Beijing, said in a statement. [Video: See Global Warming Make Earth Greener]

Fuel for plants

Green leafy flora make up 32 percent of Earth's surface area. All of those plants use carbon dioxide and sunlight to make sugars to grow — a process called photosynthesis. Past studies have shown that carbon dioxide increases plant growth by increasing the rate of photosynthesis.

Other research has shown that plants are one of the main absorbers of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Human activities, such as driving cars and burning coal for energy, account for about 10 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions per year, and half of this CO2 is stored in plants.

"While our study did not address the connection between greening and carbon storage in plants, other studies have reported an increasing carbon sink on land since the 1980s, which is entirely consistent with the idea of a greening Earth," said study co-author Shilong Piao, of the College of Urban and Environmental Sciences at Peking University.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, it wasn't clear whether the greening seen in satellite data over recent years could be explained by the sky-high CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere (the highest the planet has seen in 500,000 years). After all, rainfall, sunlight, nitrogen in the soil and land-use changes also affect how well plants grow.

To isolate the causes of planetary greening, researchers from around the world analyzed satellite data collected by NASA's Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer instruments. They then created mathematical models and computer simulations to isolate how each of these variables would be predicted to influence greening. By comparing the models and the satellite data, the team concluded that about 70 percent of the greening could be attributed to atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, the researchers reported Monday (April 25) in the journal Nature Climate Change.

"The second most important driver is nitrogen, at 9 percent. So we see what an outsized role CO2 plays in this process," said study co-author Ranga Myneni, an earth and environmental scientist at Boston University.

Warming still worrisome

While green shoots may be good, excess CO2 emissions also bring a host of more worrisome consequences, such as global warming, melting glaciers, rising sea levels and more dangerous weather, according to accumulating research.

What's more, the greening may be a temporary change.

"Studies have shown that plants acclimatize, or adjust, to rising carbon dioxide concentration and the fertilization effect diminishes over time," said Philippe Ciais, associate director of the Laboratory of Climate and Environmental Sciences in Gif-sur-Yvette, France.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.