Oil-Eating Microbes Threaten Shipwrecks and Ocean Life

The microbes that once thrived around deep-sea shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico have transformed significantly after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, according to a new study. These dramatic changes to the microorganisms that live on and near historically significant vessels could wreak havoc on the vessels and ocean life itself, researchers say.

There are more than 2,000 known shipwrecks on the ocean floor in the Gulf of Mexico, spanning more than 500 years of history, from the time of Spanish explorers to the Civil War and through World War II, according to the researchers.

"The first time I saw a chart showing the abundance of shipwrecks along our coasts, my jaw dropped," said Jennifer Salerno, a marine microbial ecologist at George Mason University in Virginia. "You can't look at an image like that and not question whether or not they are impacting the environment in some way." [Shipwrecks Gallery: Secrets of the Deep]

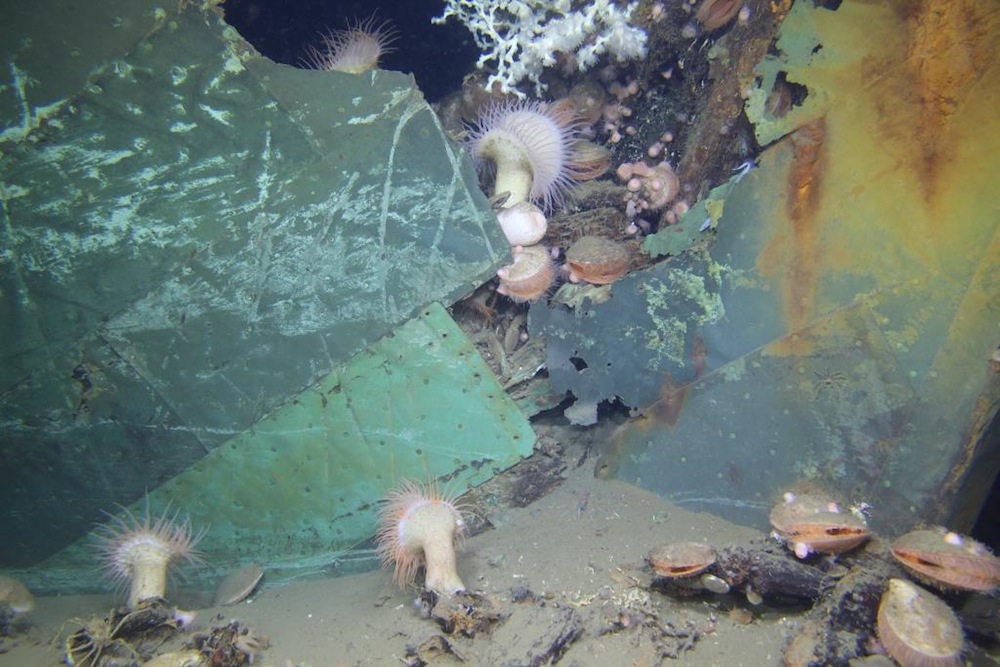

These decades-to-centuries-old wrecks can serve as artificial reefs supporting deep-sea ecosystems, "oases of life in an otherwise barren deep sea," Salerno told Live Science. "Once you put something, anything, in the ocean, microorganisms will immediately colonize it, forming biofilms. These biofilms contain chemicals produced by the microorganisms that serve as cues for other organisms like bivalves and corals to settle down and make a living on the wreck. In turn, larger and more mobile animals like fish are attracted to the presence of the smaller organisms — that is, food — and the three-dimensional structure of the ship itself, a good place to seek refuge from predators."

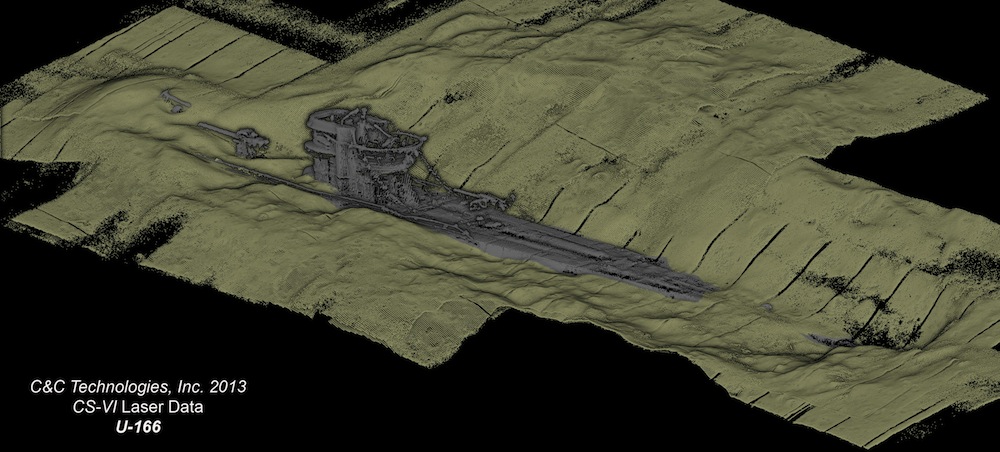

The shipwrecks might also hold untold historical secrets. "The history of our species is not only encoded in our DNA; it is found in the physical remains left behind by past human populations. Archaeological sites such as historic shipwrecks — vessels that sank more than 50 years ago — represent snapshots of time from our collective human history," said Melanie Damour, a marine archaeologist at the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, an agency within the U.S. Interior Department. "Each and every shipwreck is unique and has its own story to tell — from how, when, and where it was constructed and by whom, to how it participated in the activities that shaped who we are today."

In 2010, the Gulf of Mexico experienced the worst man-made environmental disaster in U.S. history, after explosions at the Deepwater Horizon oil rig caused more than 170 million gallons (643 million liters) of oil to spill into the water. In 2014, scientists launched a project to investigate the impacts of this catastrophe on deep-sea shipwrecks and the ecosystems they support in the Gulf — an estimated 30 percent of the oil from the spill ended up deposited in the deep sea, in areas that contain shipwrecks, the researchers said.

"What we hope to learn from this study is if those impacts will affect the long-term preservation of these sites, which, in turn, has significant repercussions for their continued ecological role and the amount of time that we have left to record their archaeological information before it is lost forever," Damour, co-leader of the research project, told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists found that shipwrecks influence which microbes are present on the seafloor. These microbes in turn form the foundation for other life, such as coral, crabs and fish.

Furthermore, the researchers found the Deepwater Horizon oil spill had a dramatic effect on nearby shipwreck microbial communities even four years after the disaster. Such changes might in turn impact other parts of their ecosystems, the researchers said. [SOS! 10 Major Oil Disasters at Sea]

Specifically, in sediment layers within the Deepwater Horizon oil plume, the scientists detected "oil snow" — cell debris and other chemicals produced by microorganisms that have come into contact with oil, making the oil heavy and causing it to sink rather than float. In this oil snow, the researchers found DNA from bacteria whose closest relatives break down oil for energy.

"There are many known microorganisms that are able to consume oil for energy and metabolism. When oil is present, they have the potential to flourish," said Leila Hamdan, a marine microbial ecologist at George Mason University and co-leader of the project.

The presence of oil-eating microbes in these sediments is not surprising, because the Gulf of Mexico has plenty of natural oil seeps. "What is surprising is that we see so many of the same species in the same place at the same time," Hamdan told Live Science. "It seems that the chemicals in this oil snow material allow a handful of microorganisms to dominate these sediments. Imagine a party invitation goes out to 400 people, and one-third of them show up wearing exactly the same dress. You would wonder why and how that happened. What cue in the invitation caused them to all go choose that same outfit from their closets? It's an exciting task to find out why it happened."

By changing what microbes dominate shipwreck habitats, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill may have had untold effects on those ecosystems, the researchers said. "These communities have evolved over millions of years to be efficient and metabolically diverse," Hamdan said. "Any time a human activity changes these communities, there is potential for harm to the ecosystem." [Coral Crypt: Photos of Damage from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill]

The scientists also found that exposure to oil spurred microbes to increase metal corrosion. This suggests that the oil spill could potentially speed up degradation of steel-hulled wrecks, said Salerno, a collaborator on the research project.

"We are concerned that the degradation of these sites a lot faster than normal will cause the permanent loss of information that we can never get back," Damour said in a statement. "These are pieces of our collective human history down there and they are worth protecting."

Future research into these unique shipwreck habitats could help protect and conserve both the life that lives there and the shipwrecks themselves, the scientists added.

"The microbial ecological and molecular biological datasets can help us track change over time and measure ecosystem recovery from the microscale," Damour said. "The marine archaeological data, especially the 3D laser and 3D acoustic scans of the shipwrecks and their immediate surroundings, can help us observe and measure macroscale change over time. Are the shipwrecks degrading faster in some areas? Are the wrecks within the spill-impacted areas collapsing or in danger of collapse in the near future? How are the resident biological communities affected? These are all questions that are worth asking."

The researchers detailed their findings on Feb. 22 at the Ocean Sciences Meeting in New Orleans.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.