Ancient Roman Tavern Found Littered with Patrons' Drinking Bowls

One of France's earliest-known Roman taverns is still littered with drinking bowls and animal bones, even though more than 2,000 years have passed since it served patrons, a new archaeological study finds.

An excavation uncovered dozens of other artifacts, including plates and bowls, three ovens, and the base of a millstone that was likely used for grinding flour, the researchers said.

The finding is a valuable one, said study co-researcher Benjamin Luley, a visiting assistant professor of anthropology and classics at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania. Before the Romans invaded the south of France, in 125 B.C., a culture speaking the Celtic language lived there and practiced its own customs. [See Photos of the Ancient Roman Tavern Discovered in France]

These Celtic people lived in densely settled, fortified sites during the Iron Age (750 B.C. to 125 B.C.), trading with cultures near and far, the researchers said. But after the Roman invasion, the Celtic culture at this location changed socially and economically, Luley said.

For instance, the new findings suggest that some people under the Romans stopped preparing their own meals and began eating at communal places, such as taverns.

"Rome had a big impact on southern France," Luley told Live Science. "We don't see taverns before the Romans arrive."

Tavern clues

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

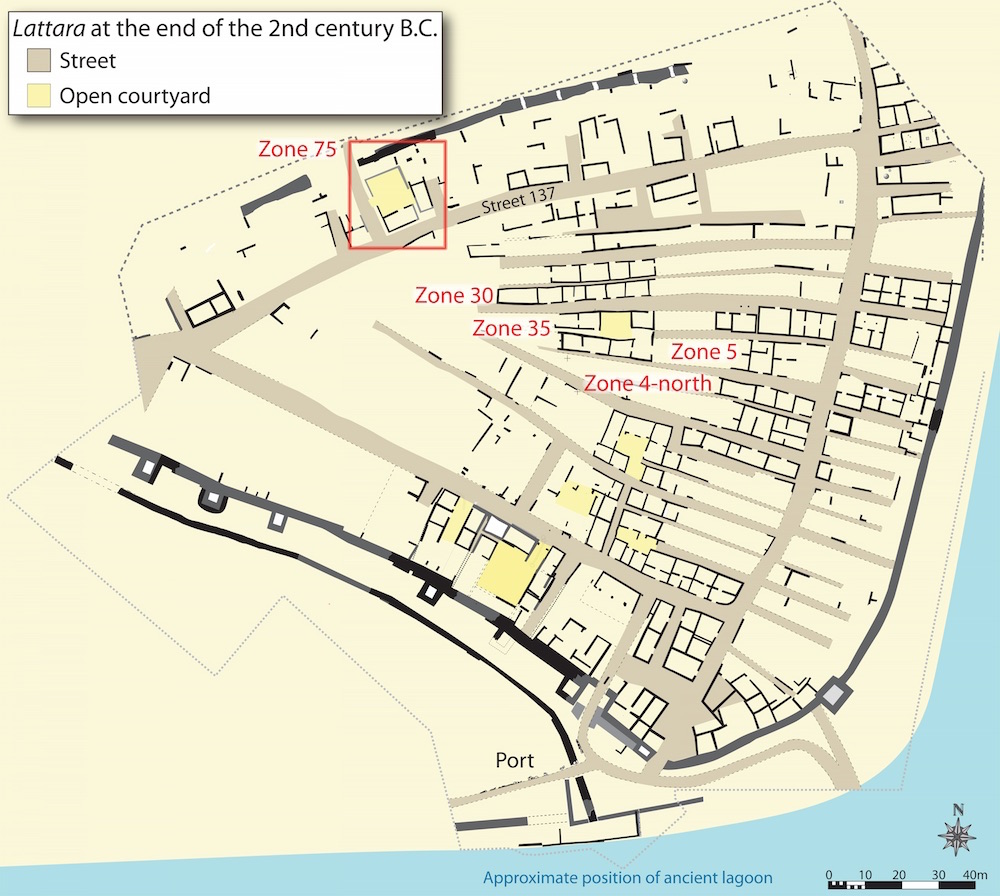

The newly excavated tavern is located at Lattara, an archaeological site that's been known to modern researchers since the early 1980s. But Luley and his colleague Gaël Piquès, a researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research, were specifically looking for artifacts dating to the end of the Iron Age, when the Romans arrived, the archaeologists said.

The researchers were in luck: The site they uncovered dates to about 125 B.C. to 75 B.C., spanning the period following the Roman conquest, and was located at the intersection of two important streets, the scientists said.

At first, the researchers weren't sure what to make of it. But a number of clues suggested the site was once a bustling tavern, one that likely served fish, flatbread, and choice cuts of cows and sheep, Luley said.

The excavated area includes a courtyard and two large rooms; one was dedicated to cooking and making flour, and the other was likely reserved for serving patrons, the researchers said.

There are three large bread ovens on one end of the kitchen, which indicates that "this isn't just for one family," but likely an establishment for serving many people, Luley said. On the other side of the kitchen, the researchers found a row of three stone piles, likely bases for a millstone that helped people grind flour, Luley said.

"One side, they're making flour. On the other side, they're making flatbread," Luley said. "And they're also probably using the ovens for other things as well." For example, the archaeologists found lots of fish bones and scales that someone had cut off during food preparation, Luley added. [Photos: Mosaic Glass Dishes and Bronze Jugs from Roman England]

The other room was likely a dining room, the researchers said. The archaeologists uncovered a large fireplace and a bench along three of the walls that would have accommodated Romans, who reclined when they ate, Luley said. Moreover, the researchers found different kinds of animal bones, such as wishbones and fish vertebra, which people simply threw on the floor. (At that time, people didn't have the same level of cleanliness as some do now, Luley noted.)

The dining room also had "an overrepresentation of drinking bowls," used for serving wine — more than would typically be seen in a regular house, he said.

Next to the two rooms was a courtyard filled with more animal bones and an offering: a buried stone millstone, a drinking bowl and a plate that likely held cuts of meat.

"Based upon the evidence presented here, it appears that the courtyard complex … functioned as a space for feeding large numbers of people, well beyond the needs of a single domestic unit or nuclear family," the researchers wrote in the study. "This is unusual, as large, 'public' communal spaces for preparing large amounts of food and eating together are essentially nonexistent in Iron Age Mediterranean France."

Perhaps some of the people of Lattara needed places like the tavern to provide meals for them after the Romans arrived, Luley said.

"If they might be, say, working in the fields, they might not be growing their own food themselves," he said. And though the researchers haven't found any coins at the tavern yet, "We think that this is a beginning of the monetary economy" at Lattera, Luley said.

The study was published in the February issue of the journal Antiquity.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus