Legionnaires' Disease Might Sometimes Spread Between People, One Case Suggests

Legionnaires' disease, a sometimes-deadly respiratory disease thought to be spread only through contaminated water, mist, vapor or soil, also may be transmitted between people, a new report of a single case in Portugal suggests.

The evidence from the case shows that "person-to-person transmission of [Legionnaires'] was the most plausible explanation" for how the woman in the case became sick, said Dr. Ana Correia, the lead author of the case report and a physician at the Northern Regional Health Administration in Porto, Portugal, in an email to Live Science.

Correia emphasized that, even if other cases confirm that person-to-person transmission of Legionnaires' disease happens occasionally, that type of transmission is likely very rare.

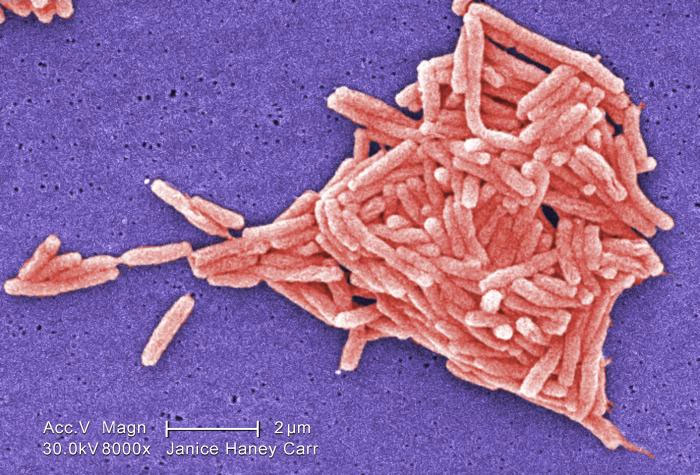

Each year, between 8,000 and 18,000 people in the United States are hospitalized with Legionnaires', according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The disease is caused by a type of bacteria called Legionella. Symptoms usually develop two to 10 days after a person is exposed to the bacteria, and tend to worsen over time without treatment. A person with Legionnaires' may initially experience loss of appetite, headache and high fever, and go on to develop a cough with phlegm or blood, as well as chest pain and confusion. The disease can develop into a fatal form of pneumonia. [5 Things You Should Know About Legionnaires' Disease]

About 5 to 10 percent of people infected with Legionnaires' die, according to the World Health Organization. The rate can be higher (up to 80 percent) among people who have weakened immune systems.

The disease was first identified in 1977, after an outbreak of pneumonia among attendees of an American Legion convention in Philadelphia. The Legionella bacteria that cause the disease grow best in warm water, such as in plumbing systems, decorative fountains and cooling towers. People can be exposed to Legionella by breathing in contaminated water droplets, breathing in drinking water (having it go down the "wrong pipe") or, in uncommon cases, through working with contaminated soil.

In late 2014, there was a large outbreak of Legionnaires' in Vila Franca de Xira, in western Portugal, with 334 cases and 10 deaths. Ninety percent of the people infected lived within about 2 miles (3 kilometers) of a cooling system, which was later found to be contaminated with the bacteria.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Correia and her co-authors looked at two cases from this outbreak, of a man and his mother.

The man was a 48-year-old maintenance worker who worked at the cooling tower complex that was later found to be contaminated, and was among the first cases identified in the outbreak. His illness began in mid-October 2014, and he developed severe respiratory symptoms, including a strong cough. During this time, he stayed with his 74-year-old mother for 8 hours before being admitted to a hospital.

The man's mother had no previous health issues but developed symptoms of Legionnaires' in late October, and was admitted to the same hospital as her son in early November. They both died — the mother on Dec. 1, 2014, and the son on Jan. 7, 2015.

Gene sequencing of the bacteria from urine samples from the mother and son revealed they had the same strain of L. pneumophila bacteria as other people in that outbreak. The samples were sequenced weeks apart to avoid cross-contamination.

As far as the researchers could tell, the woman had remained in Porto, about 186 miles (300 km) from Vila Franca de Xira, during the outbreak, according to the paper. She had never been to Vila Franca de Xira, and no other cases of Legionnaires' were reported in Porto.

The mother and son lived in a home with small rooms that had no ventilation or air conditioning. Water samples from the home all tested negative for Legionella.

Taken together, all of the evidence points to the likely conclusion that the mother was infected directly through contact with her son, the researchers wrote in their report of the case. Experts had previously hypothesized that Legionnaires' could be transmitted from person to person, but this appears to be the first time evidence from an actual case has supported this hypothesis, they said.

The U.S. has seen recent small outbreaks of Legionnaires', including one in New York City in 2015. And although the disease is still rare, the CDC reported a near tripling of U.S. cases of Legionnaires' between 1998 and 2012. The agency said the increase could be explained by the aging of the population, aging plumbing or changes in climate. It could also reflect increased diagnostic testing and reporting.

The CDC currently says on it's website that a person with Legionnaires' "is not a threat to family members, co-workers or others."

"All previous evidence indicates that Legionnaires' disease is contracted via inhalation or aspiration of contaminated water droplets from an environmental source, and proper maintenance of these sources is critical for disease control," CDC spokeswoman Kristen Nordlund told Live Science in an email. "Although we did not participate in review of these data, this interesting report suggests that person-to-person transmission may be possible in rare circumstances."

Correia said she thought this measured response was a good idea, and stressed the need for caution when evaluating this research. "We still think that the odds of person-to-person-transmission of LD are so small that, for the moment, we don't consider [it] necessary to change the information available to the public," Correia said.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.