Slipping into a Food Coma? Blame Your Gut Microbes

When you push away your plate, loosen your belt and announce, "I couldn't manage another bite!" it may be your gut microbes talking, according to a new study. Researchers found chemical clues hinting that, when certain bacteria in the belly have had enough to eat, they tell the brain that it's time to put down the fork.

About 20 minutes after a person eats, E. coli bacteria, which are common in the human gut, produce proteins that scientists have connected to a hormone responsible for appetite suppression response in the brain. This is one of the first studies to explore the mechanisms that connect microbial activity to responses in the human body associated with behavior.

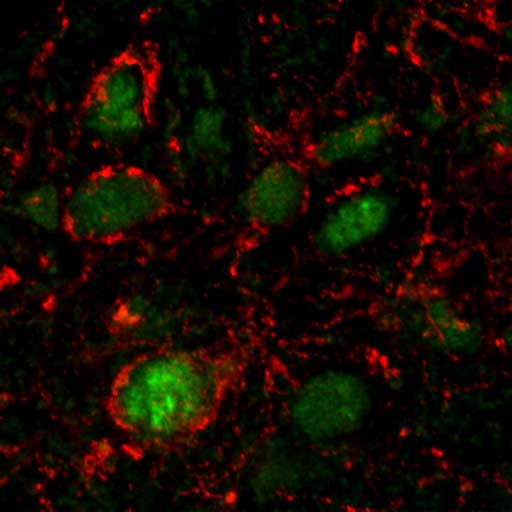

What goes into your stomach benefits not just you but also your microbes. A single human body hosts more microbes than there are people on Earth — many, many times over. About 100 trillion bacteria, viruses and fungi live in and on every body surface, from your eyelids to your intestines. But not to worry — the vast majority of these microscopic squatters aren't there to make trouble. Many are benign, and others are downright beneficial, helping your cells to process nutrients or fight off infections. [5 Ways Gut Bacteria Affect Your Health]

The biggest microbial hub in the human body is the digestive system, with 70 percent of all the body's microbes inhabiting the colon alone. One of the species of bacteria living there is E. coli. The name may conjure up unpleasant associations with bowel disorders and digestive distress, but E. coli can be found in every healthy gut, and may be an active participant in shaping your eating habits, the new study suggests.

Whenever you eat — whether it's a sumptuous holiday meal or just a snack — your microbes absorb those nutrients, too, which stimulates their reproduction. Scientists suspected that it would benefit gut bacteria to somehow signal their host to help regulate food intake, and thereby control their own numbers. So the researchers looked for signs of change in E. coli activity relative to feeding.

Sergueï O. Fetissov, of Rouen University in France and co-author of the new study, had already investigated a bacterial protein called ClpB, recognizing it as easily traceable in the gut and in the blood, he told Live Science. Recently, he and his colleagues developed a way to measure the bacterial protein so that they could compare how much of it the E. coli bacteria produced before and after the bacteria fed.

They noted that about 20 minutes after feeding, the E. coli bacteria produced about twice as much of the ClpB protein as they did before they fed. The timing of this change showed a promising alignment with known human behavior — 20 minutes after eating is usually when people first start to feel full.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The next step was to see what — if any — effect the release of more ClpB in E. coli's postmeal protein cocktail might have on the host body. They found that this particular blend of proteins reduced food intake when it was injected into mice and rats.

Further tests showed that the proteins stimulated the release of a hormone called peptide YY, or PYY.

"PYY is one of the main hormones released from the gut after a meal, so it signals satiety to the brain," Fetissov told Live Science. "It starts to be released about 20 minutes after the meal. So, if you look at the dynamic of the bacterial growth, they fit perfectly with the dynamic of PYY release in the blood after the meal."

Still, E. coli is only a minor player in the human gut, representing just 1 percent of the bacteria in the colon. Fetissov expects that many exciting discoveries will emerge from analysis of other types of bacteria. He added that he would not be surprised to find that bacteria are involved in the control of numerous molecular pathways that influence other types of emotions and motivated behaviors.

"We will continue to look into the mechanism of how that bacteria can regulate appetite, particularly in people who are obese or who suffer from binge-eating disorders," Fetissov said. "And if we find some involvement, I hope we can also treat these conditions."

The findings were published online today (Nov. 24) in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.