Triceratops' Teeth Turned Into Slicing Machines While Chewing

Triceratops is known for its distinguished trio of horns, but the dinosaur's teeth are just as distinctive, a new study finds. An analysis of 66-million-year-old Triceratops' teeth shows they are more complex than reptilian teeth, and rival the complexity of chompers found in mammals' mouths.

"These are really sophisticated teeth, in fact more sophisticated then I'd thought they'd be," said the study's co-researcher Gregory Erickson, a professor of paleobiology at Florida State University. The dinosaurs' teeth are so sophisticated that they actually transformed into knives of sorts while the beast was eating.

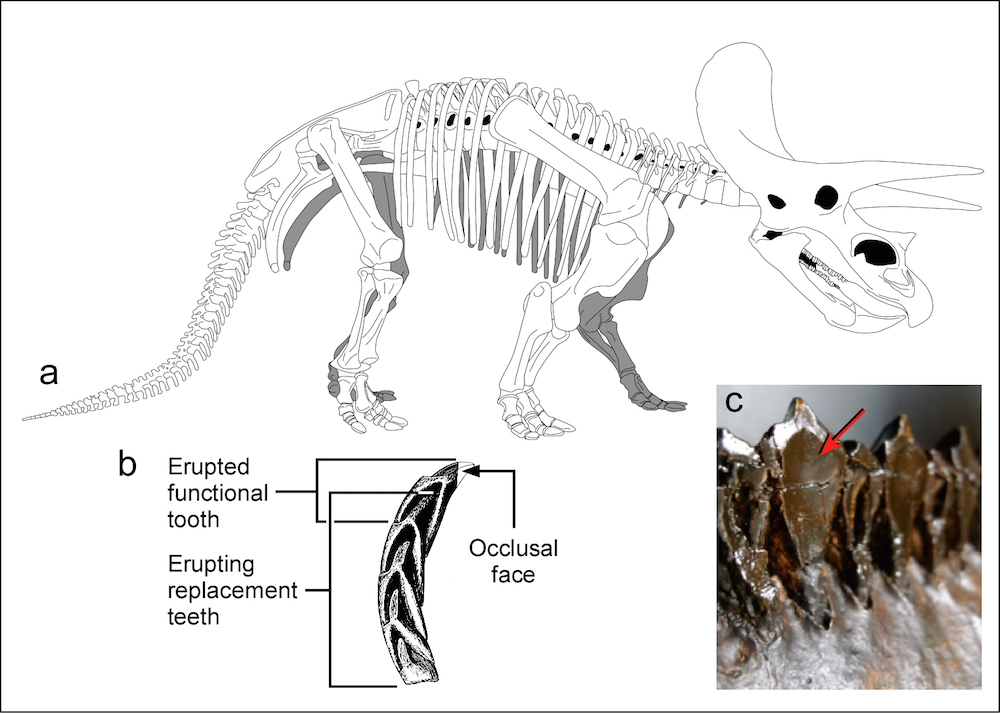

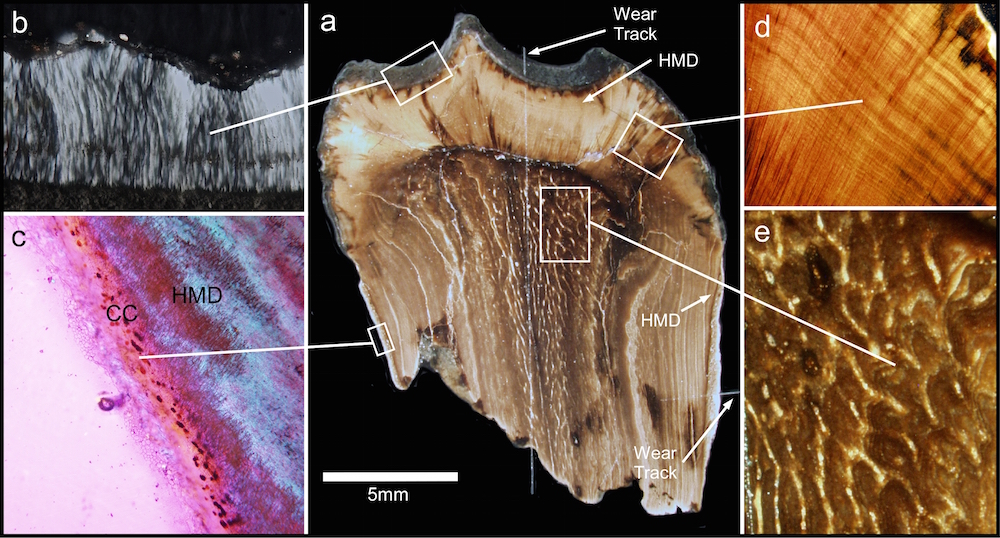

Triceratops' teeth have five layers of tissue, the researchers found. To put that in perspective, crocodiles' and other reptiles' teeth have just two layers: enamel over a core of dentine, a calcified tissue denser than bone, Erickson said. Horse and bison, once thought to have the most complex teeth of any animal, have four layers. [See a video about the Triceratops' complex teeth]

Of the Triceratops' five layers, the vasodentine — a layer of hard but porous dentine filled with blood vessels — is one of the most important. Vasodentine is rare and hasn't been seen outside of bony fishes, the researchers said.

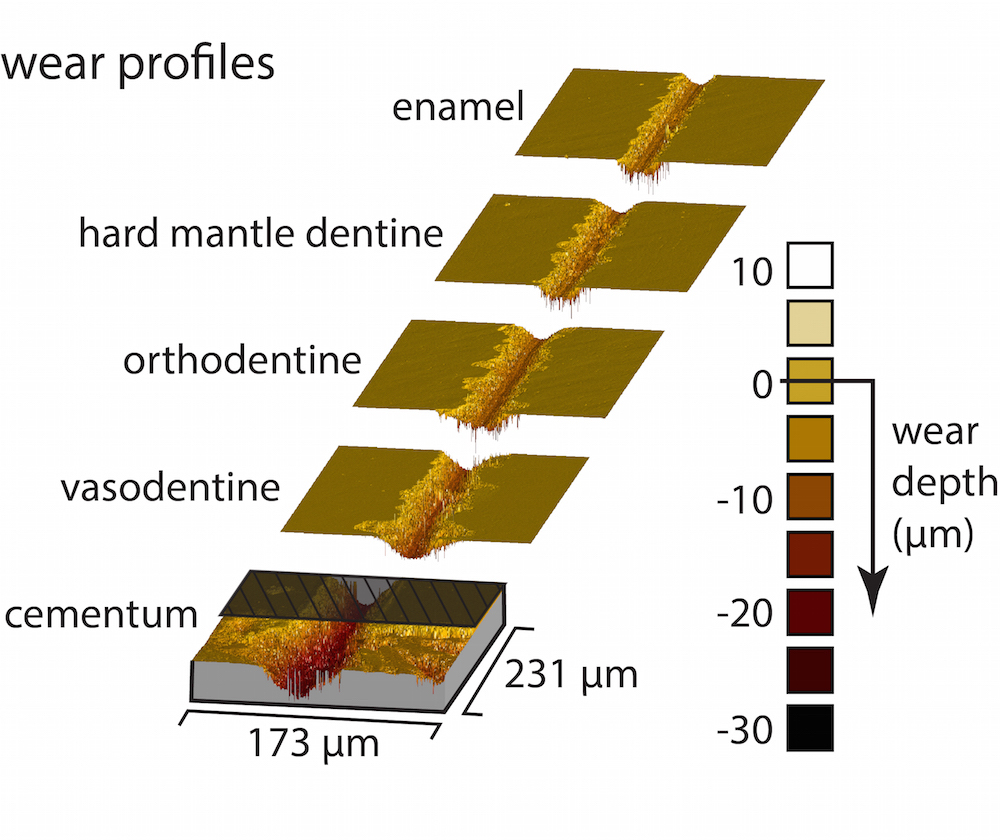

"The porosity actually made it less wear-resistant," said study co-researcher Brandon Krick, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. As Triceratops chewed its food, the vasodentine wears over time "into this scalloped valley on the surface of the teeth. It's a lot like some chef knives you'll see."

These chompers were also an evolutionary advantage: They may have helped Triceratops eat a greater variety of plants, giving the species an advantage over other herbivorous dinosaurs, the researchers said.The scalloped valleys would have made slicing more efficient, and increased the pressure at the slicing edges so that the dinosaur could chew its food without putting too much force on its teeth, Krick said. The valleys also would have reduced contact between the teeth and the dinosaur's leafy meals, reducing the amount of friction and making chewing more efficient, he said.

Toothy project

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Triceratopsdinosaurs are hardly the only animals with self-wearing teeth. Many mammals (but not really humans) have teeth that change shape with use, Erickson said. For instance, the teeth of most herbivorous mammalswear down to create complex file surfaces that can mince plants, the researchers said.

Self-wear is less common in reptiles, which have pointy teeth. These animals usually use their teeth to seize or crush prey, not chew it, the researchers said.

To get a better look at the Triceratops' teeth, a team of paleobiologists and engineers examined a few teeth from the species Triceratops horridus. Using a special tool called a microtribometer (a machine that measures the friction and forces between two solid surfaces), the researchers made nanosized indentations in the teeth using a diamond-tipped microprobe. These indentations helped the scientists identify the different layers on the teeth, as well as the chompers' hardness and wear resistance.

"We found that material properties in 66-million-year-old teeth are preserved," Erickson said. "If you put them into a dinosaur today, they would work just fine."

The researchers created a computer model that showed, in 3D, how each tissue wore down and how the Triceratops developed their uniquely scalloped teeth. This model can also be used for industrial and commercial applications, Krick said.

Erickson and Krick previously worked together on duck-billed hadrosaurid teeth, finding that these herbivorous dinosaurs, which also lived during the Late Cretaceous, had six-layered teeth.

Through this work, the researchers have learned that "dinosaur teeth are much more complex architecturally and biomechanically than we ever realized," Erickson said. "I think that helped fuel their success."

The findings were published online today (June 5) in the journal Science Advances.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.