Doctor Who Survived Ebola Nearly Lost His Vision

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An American doctor who recovered from Ebola developed serious eye problems months later because the virus had lingered in his eye, according to a new report of his case.

Dr. Ian Crozier, now 44 years old, contracted Ebola in September 2014 while treating patients in Sierra Leone. Crozier's eye problems were so serious that he nearly lost his vision, but his sight has since recovered, according to the new report, which Crozier co-authored.

"This case highlights an important complication of [Ebola virus disease], with major implications for both individual and public health that are immediately relevant to the ongoing West African outbreak," the researchers wrote in the report, published online today (May 7) in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Shortly after Crozier became ill in Africa, he was evacuated to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, where he received intensive treatment, including being placed on a ventilator for 12 days and undergoing dialysis for kidney failure for nearly a month.

After more than 40 days of treatment, his condition improved. He was declared Ebola-free and was released from the hospital.

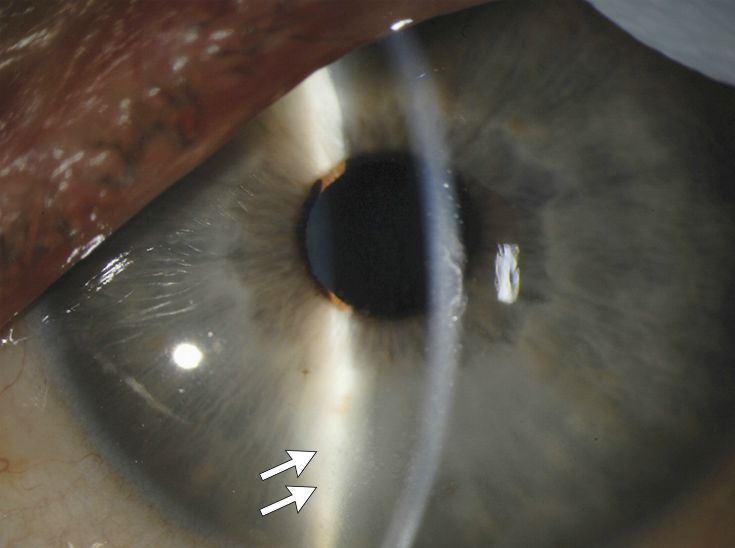

But he soon began to experience eye problems, including a burning sensation and the feeling that there was something in his eye, according to the report. He also needed a new prescription for his reading glasses. Following an eye exam, Crozier was diagnosed with uveitis, an inflammation of the uvea, or the middle tissue layer of the eye.

One month later, about nine weeks after he had been declared Ebola-free, Crozier had new eye symptoms, including redness, blurred vision with halos and pain, and increased pressure in his left eye. He was started on treatment with eye drops to reduce the eye inflammation, and drugs to lower the pressure in his eye. [What Are the Long-Term Effects of Ebola?]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But his symptoms continued to worsen over the next few days, so his doctors performed a procedure to remove fluid from his eye, and tested it for the Ebola virus.

They found that a sample from the aqueous humor — the fluid between the eye's outer covering and the lens — tested positive for Ebola. However, samples of Crozier's blood, tears and conjunctiva tissue (which lines the eyelid and white part of the eye), tested negative for Ebola.

Over the next five days, Crozier's eye inflammation continued, and he experienced some vision loss. Three days later, the inflammation improved, but he still had severe vision impairment in his left eye.

Three months after his first diagnosis with eye inflammation, his condition had improved and he had recovered his vision, the researchers said.

There have been previous reports of eye problems in Ebola survivors. After the 1995 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, about 15 percent of survivors in a follow-up study had developed eye problems, such as eye pain and vision loss. And a recent survey of 85 Ebola survivors in Sierra Leone found that 40 percent reported eye problems.

Crozier's eye problems were likely a direct effect of the Ebola virus, which persisted in the eye fluid despite being cleared from most of the body, the researchers said. (Another place where Ebola can persist after recovery is in the semen.)

It's reassuring that the Ebola virus was not found in parts of the eye that could come into contact with others, such as tears and the conjunctiva, the researchers said. This finding "supports previous studies suggesting that patients who recover from [Ebola virus disease] pose no risk of spreading the infection through casual contact," the researchers said.

Future studies are needed to assess how the Ebola virus is able to persist in certain sites in the body, the researchers noted.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus