Photos: 9,000-Year-Old Bison Mummy Found in Siberia

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In 2011, the preserved remains of a Steppe bison (Bison priscus) — an ancient relative of modern bison — was uncovered by a tribe in North Siberia's Yana-Indigirka Lowland. Researchers have performed a thorough necropsy, or autopsy, of the frozen creature, and the results are being presented today (Nov. 6) at a conference in Berlin. The findings will also be published in an upcoming edition of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Here's a look at this incredible, ancient creature: [Read full story about the bison mummy]

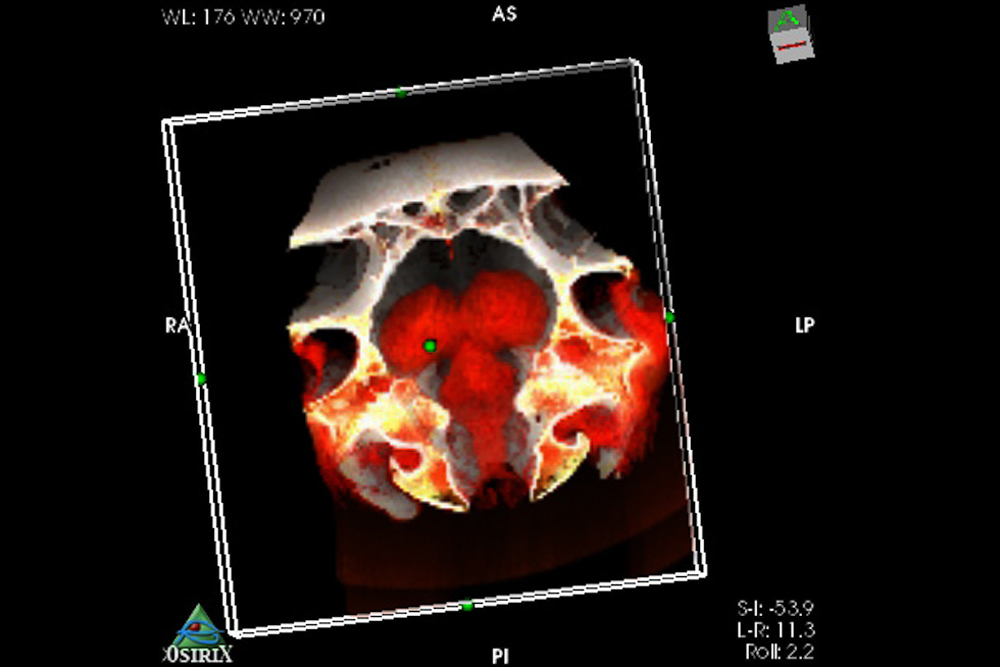

Bison brain scan

The freezing conditions of northern Siberia left the Yukagir bison mummy's brain — as well as all of its other internal organs — almost perfectly persevered. The researchers performed a computerized tomography, or CT, scan on the mummy's brain, an image of which can be seen here. In the months to come, the researchers will compare the data they gather about this ancient animal's organs to data they've collected from modern specimens of American bison (Bison bison). (Credit: Dr. Albert Protopopov)

Bison mummy discovery

Members of the Yukagir tribe in the Yana-Indigirka Lowland of northern Siberia discovered the bison mummy along the melting shores of a lake. The mummy was loaned to a regional Academy of Science, where it was kept frozen until it could be thoroughly examined by researchers. (Credit: Grigory Gorokhov)

Well-preserved remains

This specimen is the most complete frozen mummy of the Steppe bison yet known, the researchers said. The so-called Yukagir bison mummy has a complete brain, heart, digestive system and blood vessels, but some of the animal's organs have shrunk significantly over time. (Credit: Dr. Gennady Boeskorov)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bison necropsy

The brain and other internal organs of the bison mummy were well preserved after nearly 10,000 years in the frozen ground. (Credit: Dr. Evgeny Maschenko)

Frozen in time

The necropsy revealed a relatively normal anatomy with no obvious cause of death. The procedure did, however, find a lack of fat around the animal's abdomen, which suggests the animal may have died from starvation. (Credit: Dr. Evgeny Maschenko)

Siberian specimen

Russian scientists, including researchers at the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Paleontological Institute in Moscow, are some of the people involved with the project. (Credit: Dr. Natalia Serduk)

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus