Ice Age Extinctions Could Predict Modern Die-Offs

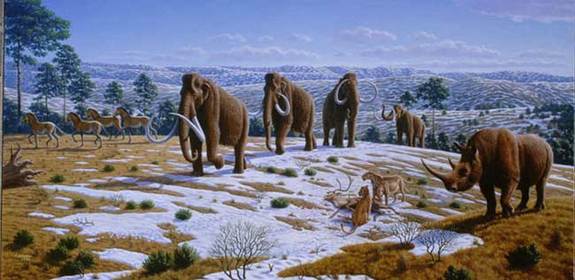

During the last Ice Age, huge mammals roamed North America. Those mammoths, saber-toothed cats and giant sloths disappeared about 12,000 years ago — the same time as humans arrived and Earth's climate warmed from its glacial chill.

Scientists have long debated the cause of the mass extinction, whether humans or climate change. But now, researchers are beginning to turn from investigating the cause to better understanding its impact. The loss of so many of those large species, or megafauna, could help researchers predict what will happen as modern-day mammals such as elephants, rhinoceroses and tigers disappear.

"We've already had this natural experiment of losing the large, apex consumers," said Felisa Smith, a paleoecologist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, speaking of the ice age extinctions. "I'm not interested in exploring who did it. I'm interested in what happened when tens of millions of large bodies went extinct."

Smith and her collaborators are excavating fossils from Hall's Cave in Texas, a limestone cave southwest of Austin that records the transition from the ice age to a modern climate. [Image Gallery: Stunning Mammoth Unearthed]

Of the 15 herbivore species in the area before the extinction, three remain, Smith said. Those three survivors are the bison, pronghorn and deer. The top predators also shifted, according to preliminary results Smith presented Sunday (Oct. 19) at the Geological Society of America's annual meeting in Vancouver, British Columbia.

The researchers plan to investigate whether the surviving species shifted toward bigger or smaller bodies after the extinction event. They'll also search for evidence that both plant and meat eaters changed their diets.

"Most of the large mammals in the world today are in peril," Smith told Live Science. "This is an analogue for what is happening right now around the world."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Big animals have a huge impact on the world around them, from the fertilizing excrement they produce to their huge, ecosystem-tromping feet. The loss of so many species during the ice age extinction jolted local ecosystems across North America, research has shown. For example, grassy plains grazed by huge herbivores transformed into shrubland and forests. Ground-dwelling mammals like gophers expanded their range across formerly trampled ground.

"Places look different when large apex consumers are absent," Smith said.

In the present day, the dramatic population decline of African elephants has affected tropical rainforests in West and Central Africa, according to several studies. For instance, some trees depend on elephants to spread seeds.

In March, scientists from around the world gathered at Oxford University in the United Kingdom for a conference examining the interplay between megafauna and ecosystems. Some researchers at the conference argued for "rewilding," a concept that encompasses both restoring surviving populations of large animals and, at its more extreme bent, the reintroduction of extinct species like the mammoth.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus