MERS Victim Caught Deadly Disease from Camel

A man in Saudi Arabia who died from Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) appears to have caught the deadly disease from a camel he owned, a new study says.

The man, a 44-year-old who owned a herd of nine camels, was admitted to the hospital in November 2013 for severe shortness of breath. About a week before he became ill, the man had reportedly applied a medication to the nose of one of his camels that was sick and had a nasal discharge.

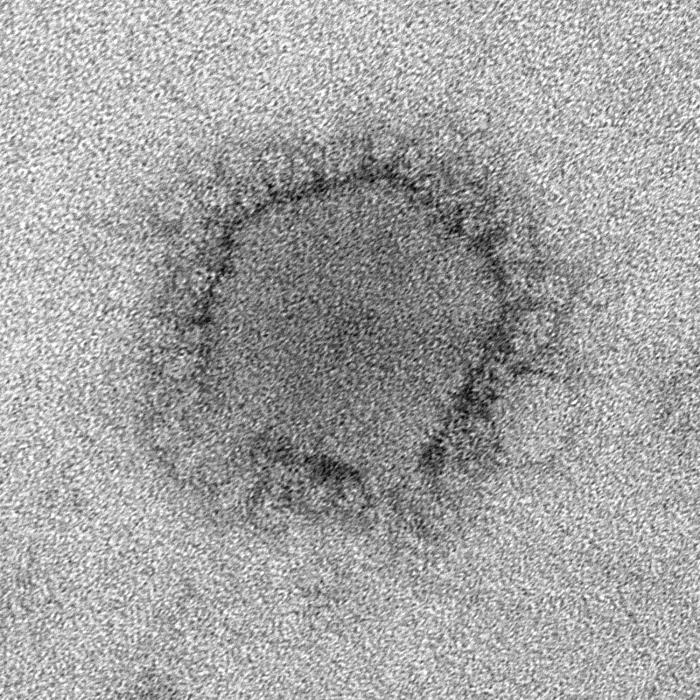

Researchers collected nasal and blood samples from the man and from all the camels, and screened the samples for the virus that causes MERS, known as MERS-Coronavirus, or MERS-CoV.

The virus was detected in the man and one of the camels — the same camel the man had treated for nasal discharge, called Camel B by the researchers. What's more, the viruses in the man and Camel B were genetically identical. [8 Things You Should Know About MERS]

Previous studies have shown that camels are carriers of MERS-CoV, and that most camels in Saudi Arabia have been infected with this virus, or a very similar one, at some point in their lives. However, it was not known whether camels could infect people directly, or if humans caught the virus from another source.

The researchers also tested the blood samples for antibodies, which are immune system proteins, against MERS-CoV. The man did not have antibodies against MERS on the day he was admitted to the hospital, but had high levels of these antibodies two weeks later — a sign that his body was fighting the infection.

Although Camel B was the only animal to have the virus itself, many of the camels had antibodies against it, which shows they had been infected in the past, the researchers said. Moreover, some of the animals already had high antibody levels at the time the man was admitted to the hospital, indicating that they were infected before the man, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings suggest that "a dromedary [one hump] camel was the source of MERS-CoV that infected a patient who had had close contact with the camel'ts nasal secretions," the researchers, from King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, wrote in the June 4 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The first cases of MERS appeared in September 2012 in Saudi Arabia, and the disease has since sickened at least 681 people worldwide, including 204 who died, according to the World Health Organization. For the man in the new report, his condition deteriorated at the hospital, and he died 15 days later.

"There's been a bunch of other evidence that's been very, very suggestive," that camels can transmit MERS to people, said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, who was not involved in the study. But the new study shows "without a doubt" that this transmission can happen, Schaffnersaid. "It crosses the T's and dots the I's very elegantly," he said.

However, there are still more questions to be answered, such as how often camels spread MERS to people, and if there are other sources of the disease besides camels, Schaffnersaid.

The study also cannot determine the virus "reservoir," that is, where the virus lies when it is not infecting people or camels, the researchers said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.