Origin of MERS Virus Found in Bats

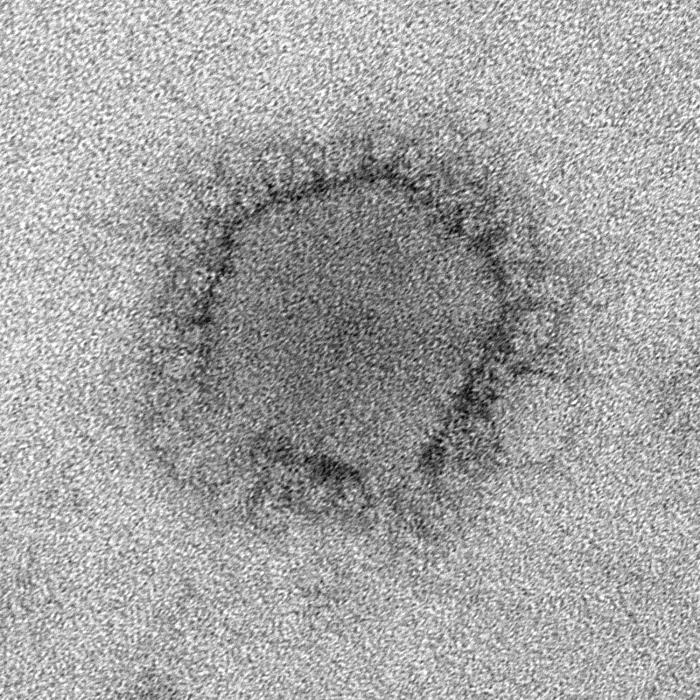

The virus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) has been found in bats in Saudi Arabia, suggesting a potential origin for the disease, according to a new study.

Researchers tested samples from bats living about 7 miles away from the home of the first person known to be infected with MERS in Saudi Arabia.

A virus found in one of the bats was 100 percent identical to the MERS virus seen in people, the researchers said.

"There have been several reports of finding MERS-like viruses in animals. None were a genetic match. In this case, we have a virus in an animal that is identical in sequence to the virus found in the first human case. Importantly, it’s coming from the vicinity of that first case," study researcher Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, said in a statement.

MERS first appeared in Saudi Arabia in September 2012, and has since infected 94 people and caused 46 deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

The researchers noted that bats are known to be reservoirs of other viruses that can infect people, including rabies and SARS, the severe respiratory illness that sickened more than 8,000 and killed nearly 800 in Southeast Asia in 2002 and 2003. [Why MERS Is Not the New SARS]

Because people often don't come in contact with bats, the researchers suspect that bats may infect other animals, which in turn, infect people. The researchers said they will continue to look for the virus in other domestic and wild animals in the region.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A study published earlier this month found that camels in Oman, a country in the Arabian peninsula, had developed antibodies against the MERS virus. This suggests that the camels were infected in the past with the MERS virus, or a very similar one, the researchers said. However, the actual virus was not found in the animals.

The new study is published today (Aug. 21) in journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. FollowLiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.