8 Things You Should Know About MERS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently announced the second case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in the United States. Here are answers to commonly asked questions about this deadly disease.

What is MERS?

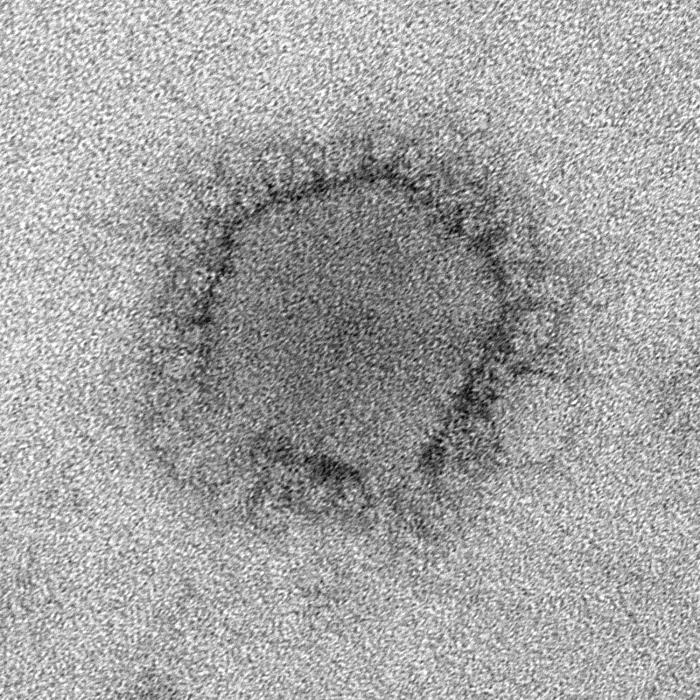

MERS is a respiratory condition caused by a virus that's only recently been seen in humans. Symptoms include fever, cough and shortness of breath. Cases of MERS first appeared in September 2012 in Saudi Arabia, and the virus has since sickened more than 500 people in 14 countries. Close to 30 percent of infected people have died. Most cases have been in the Middle East, particularly in Saudi Arabia. The virus that causes MERS is called MERS coronavirus.

Is MERS the same as SARS?

No. Both MERS and SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)belong to the same family of viruses, called coronaviruses, but the two viruses are not the same.

Unlike SARS, which tended to affect younger and healthier people, many people infected with MERS have had underlying chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart or kidney disease.

Where does MERS come from?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers don't know for sure. The MERS coronavirus has been found in camels in Egypt, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, according to the World Health Organization. But researchers can't say for sure if people caught the disease from camels. For example, it could be that another animal infects both humans and camels. The MERS virus has also been found in bats.

Has MERS come to the United States?

Yes, there have been two confirmed cases of MERS infection in the United States. Both cases were in people who caught the virus abroad and traveled to the United States.

The first case was in a person who traveled from Saudi Arabia to Chicago in late April, and took a bus to Indiana. The patient has fully recovered, and none of the patient's close contacts have signs of MERS.

The second case was in a health care worker who left from Saudi Arabia to travel to Orlando on May 1, and has since been hospitalized. Health officials are notifying and tracking people who had close contact with the patient.

What risks do these two cases pose to the U.S. public? Can you get MERS from public transportation?

Health officials say the risk of MERS to the general U.S. public from the two MERS cases is extremely low. Transmission of MERS appears to require close contact, and most cases of human-to-human transmission have occurred in people who cared for those who were sick.

In both known U.S. cases, the CDC contacted people who were on the same flight as the patient, but an agency spokesperson said this was out of an "abundance of caution."

Has there been an increase in MERS cases lately?

Yes. Since late March, there have been 330 new cases of MERS worldwide, most in Saudi Arabia. Prior to that, there were fewer than 200 cases over the 1.5-year period between September 2012 and February 2014.

What's the reason for the increase? Is the virus mutating?

The reason for the recent increase in MERS cases is not fully understood. A number of the new cases occurred during outbreaks in hospitals, but there has also been a rise in "sporadic" cases, in which patients did not have contact with anyone else who had MERS, according to WHO.

Some of the increase may have been a result of better monitoring efforts, according to Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the CDC, meaning health officials are detecting more cases. Health officials have sequenced the genome of the virus, and so far, it does not appear to be mutating, Friedensaid, speaking at a news conference Monday.

How long does it take to develop symptoms after you've been exposed to the virus?

The time between someone's exposure to the virus and when he or she becomes sick is usually about five days, and 14 days at the most, according to the CDC.

People who develop fever and cough or shortness of breath within two weeks of traveling to countries in or near the Arabian Peninsula should see their doctor, and tell them about their travel history, the CDC says.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.