Off to See the Wizard? Ancient Fossils Had Heart and Brain

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

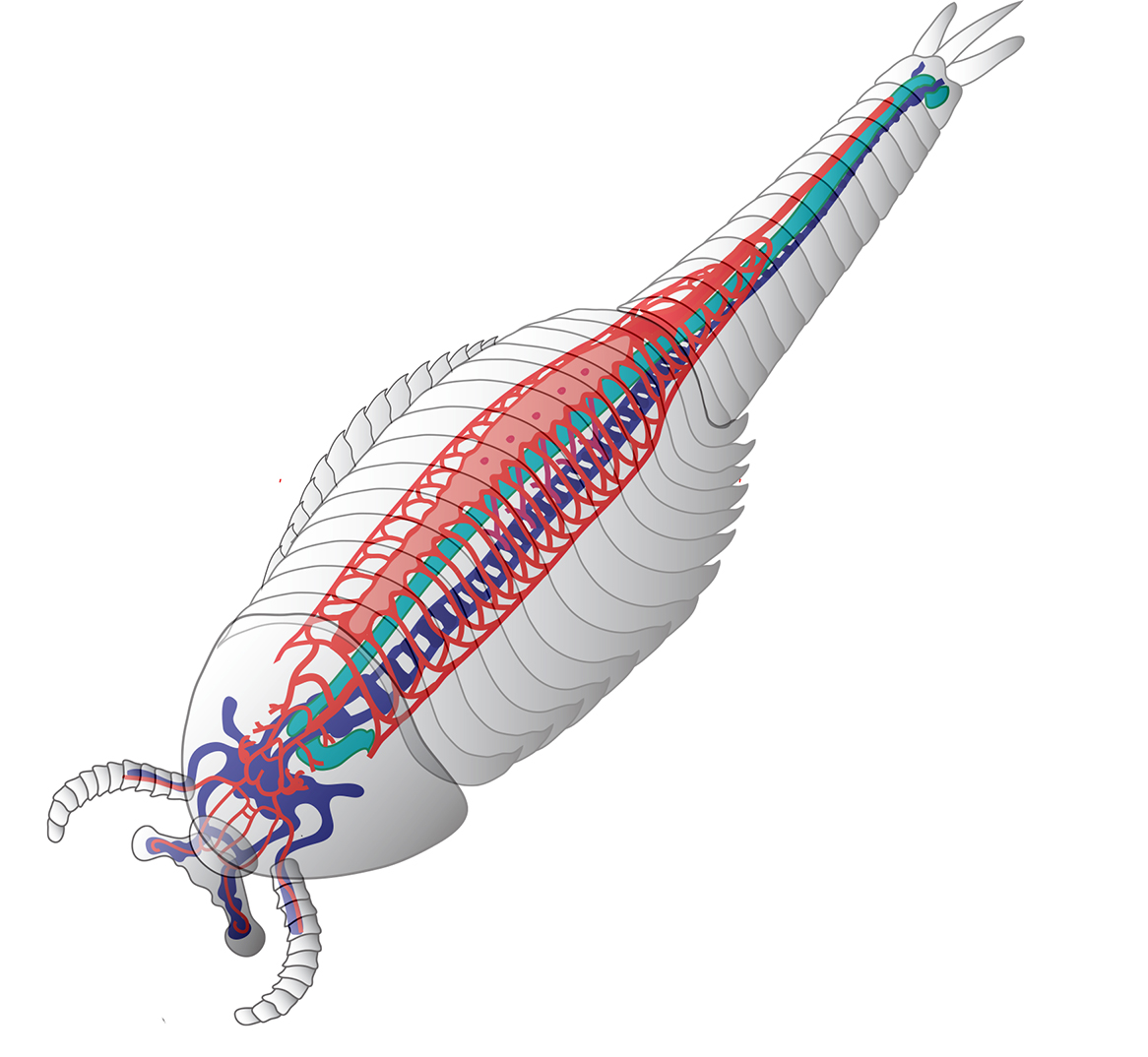

The fossil of an extinct marine predator that lay entombed in an ancient seafloor for 520 million years reveals the creature had a sophisticated heart and blood-vessel system similar to those of its distant modern relatives, arthropods such as lobsters and ants, researchers report today (April 7).

The cardiovascular system was discovered in the 3-inch-long (8 centimeters) fossilized marine animal species called Fuxianhuia protensa, which is an arthropod from the Chengjiang fossil site in China's Yunnan province. It is the oldest example of an arthropod heart and blood vessel system ever found.

"It's really quite extraordinary," said study co-author Nicholas Strausfeld, a neuroscientist at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

The cardiovascular network is the latest evidence that arthropods had developed a complex organ system 520 million years ago, in the Cambrian Period, the researchers said. Arthropods come in a wide range of shapes and sizes today, but the animals have kept some aspects of their basic body plan since the Cambrian. For instance, the brain in living crustaceans is very similar to that of F. protensa, which is a distant relative — but not a direct ancestor of — modern species, Strausfeld said. "The brain has not changed much over 520 million years," he said.

In contrast, blood vessel networks have become both simpler and more complex in the ensuing millennia, in response to changing bodies. The modern relatives of F. protensa are arthropods with mandible jaws, and include everything from insects such as beetles and flies to crustaceans such as shrimp and crabs.

"What we're seeing in the arterial system is the ground pattern, the basic body pattern from which all these modern variations could have arisen," Strausfeld told Live Science.

In the fossil, the creature's organs were preserved like a carbon 'copy.' Its hard exoskeleton is extremely faint, but the soft, internal organs became a dark-brown carbon imprint on fine-grained rock called mudstone. [Fabulous Fossils: Gallery of Earliest Animal Organs]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The animal had a tube-shaped heart positioned near its back, rather than toward the front. The blood vessels extended from the heart along its body segments and clustered near the eyes and brain, which suggests these organs required a rich oxygen supply. The fossil also has eyestalks, antennae, legs and a brain, the researchers reported.

The heart and blood vessels were identified in a fossil in the collection at the Yunnan Key Laboratory for Palaeobiology in China, by an international team of researchers led by London Natural History Museum paleontologist Xiaoya Ma. The findings were published in the April 7 issue of the journal Nature Communications.

In 2012, the same team also reported the oldest example of an arthropod brain, in a different Chengjiang F. protensa fossil.

Strausfeld described the Chengjiang fossil depositas a seafloor "Pompeii" — akin to the Roman city buried in volcanic ash — because of its remarkable preservation of soft body parts such as eyes, guts and brains. The abundance of fossil species in Chengjiang rivals that of the Burgess Shale in Canada, and provides the oldest glimpse into the Cambrian Explosion, when life rapidly diversified into the wide range of body plans known today.

"520 million years ago, we had these basic [body] patterns appear that have been maintained over time," Strausfeld said. "The search is on for the ancestors of these early animals. The question is, what came before?"

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus