Quaternary Period: Climate, Animals & Other Facts

The Quaternary Period is a geologic time period that encompasses the most recent 2.6 million years — including the present day. Part of the Cenozoic Era, the period is usually divided into two epochs — the Pleistocene Epoch, which lasted from approximately 2 million years ago to about 12,000 years ago, and the Holocene Epoch, which began about 12,000 years ago.

The Quaternary Period has involved dramatic climate changes, which affected food resources and brought about the extinction of many species. The period also saw the rise of a new predator: man.

Climate

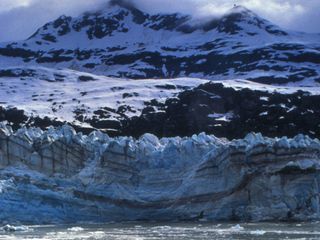

Scientists have evidence of more than 60 periods of glacial expansion interspersed with briefer intervals of warmer temperatures. The entire Quaternary Period, including the present, is referred to as an ice age due to the presence of at least one permanent ice sheet (Antarctica); however, the Pleistocene Epoch was generally much drier and colder than the present time.

Although glacial advancement varied between continents, about 22,000 years ago, glaciers covered approximately 30 percent of Earth’s surface. Ahead of the glaciers, in areas that are now Europe and North America, there existed vast grasslands known as the “mammoth steppes.” The mammoth steppes had a higher productivity than modern grasslands with greater biomass. The grasses were dense and highly nutritious. Winter snow cover was quite shallow.

Animals

These steppes supported enormous herbivores such as mammoth, mastodon, giant bison and woolly rhinoceros, which were well adapted to the cold. These animals were preyed upon by equally large carnivores such as saber toothed cats, cave bears and dire wolves.

The latest glacial retreat began the Holocene Epoch. In Europe and North America the mammoth steppes were largely replaced by forest. This change in climate and food resources began the extinction of the largest herbivores and their predators. However climate change was not the only factor in their demise; a new predator was making itself known.

Ascent of man

Homo erectus was the first hominid species to widely use fire. There are two hypotheses about the species’ origin. The first hypothesis is that the species originated in Africa and later dispersed throughout Eurasia, able to exploit the colder regions with the use of fire and tools. The second hypothesis is that Homo erectus migrated to Africa from Eurasia. Excavations in Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia, have uncovered fossil evidence that H. erectus was a successful hunter.

Homo neanderthalensis existed from about 200,000 years ago to about 30,000 years ago. Fossil evidence has shown that the species lived in much of western Europe including southern Great Britain, throughout central Europe and the Ukraine and as far south as Gibraltar and the Levant. Neanderthal fossils have not been found in Africa. Neanderthals were shorter and stockier than modern humans with longer, stronger hands and arms. Neanderthals lived in shelters, made and wore clothing, and used diverse tools made of stone and bone.

Climate conditions required a diet heavy in animal protein so they were sophisticated hunters, although a recent discovery indicates they also cooked and ate plant materials. Recent finds also prove that they deliberately buried their dead and made ornamental or symbolic objects. No earlier hominid species has been shown to practice behaviors that indicate some use of language.

Evidence suggests that Homo sapiens originated in Africa; the oldest fossils of anatomically modern humans, found in Ethiopia, are approximately 195,000 years old. By 100,000 years ago they had dispersed as far north as modern Israel, but the oldest fossils of modern humans found farther north are only 40,000 to 60,000 years old, coinciding with a brief interglacial interval.

It is clear that Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis were contemporaries for a time. Dental evidence indicates that H. sapiens matured later than Neanderthals. This suggests that a longer childhood allowed more time for social development and transmission of knowledge and technology to new generations. This possibly led to division of labor allowing females and young to forage for more diverse food sources. Diversification in diet could have been a species advantage for H. sapiens when the climate cooled again.

The most recent Neanderthal remains are about 28,000 years old. For whatever reason, Homo sapiens weathered the drastic climate changes and continued to disperse throughout the Earth while Neanderthals became extinct.

Migration to America

Between 13,000 to 10,000 years ago, at the beginning of the Holocene Epoch, lowered sea levels exposed the Bering Land Bridge between Siberia and Alaska. Snowfall in this area would have been relatively light due to the rain shadow effects of the Alaska Range, so with the glaciers covering most of Europe, it was natural for H. sapiens to follow migrating animals into North America.

Then, about 12,000 years ago, nearly three-fourths of North America's large animals, including woolly mammoths, horses and camels were wiped out. Scientists have long debated what caused this catastrophic extinction event. One explanation is that increasing global temperatures caused the glaciers to retreat. Increasing sea levels submerged the land bridge again, and forests began to replace the mammoth steppes. Changes in habitat undoubtedly put stress on animal populations.

The mass extinction also coincided with the arrival of humans in the area. Some scientists say that overhunting was a major contributor to the mass extinctions. Another theory is that a comet slammed into the glaciers of eastern Canada about 12,900 years ago, which would have drastically affected the climate and set off a new era of glacial conditions.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.