DNA analysis spanning 9 generations of people reveals marriage practices of mysterious warrior culture

Researchers reconstructed the relationships among nearly 300 Avars, people from a 1,500-year-old mysterious warrior culture in the Carpathian Basin.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hundreds of skeletons found in cemeteries on the Great Hungarian Plain reveal clues about nine generations of Avars, a mysterious warrior culture that dates back nearly 1,500 years. A new analysis of the remains suggests that men stayed put while women married into the culture and that it was common for people to have multiple partners.

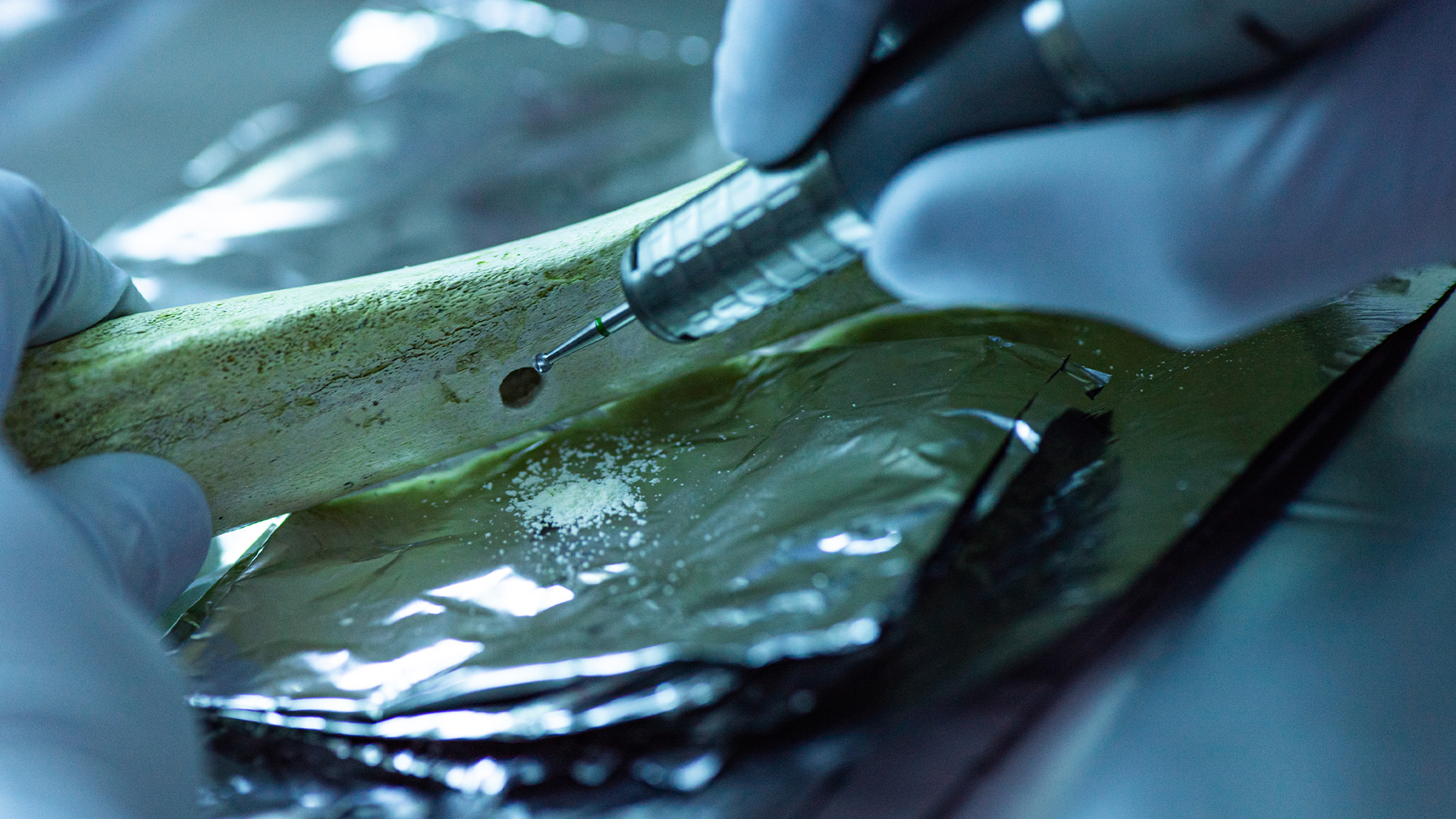

In a study published Wednesday (April 24) in the journal Nature, an international team of researchers conducted DNA analysis on 424 skeletons located in four Avar cemeteries in present-day Hungary. Based on those results, the team identified 298 people who were closely biologically related, and they mapped out family trees across nearly three centuries.

The Avar people settled in the Carpathian Basin starting in the mid-sixth century. The political core of this group included a khagan, a political leader who was surrounded by elite horse-mounted warriors and their families. Originally nomadic, the Avars established stable settlements in the early seventh century and buried their dead in large cemeteries, sometimes in ostentatious tombs filled with weapons, jewelry and horses. Although the Avars controlled a large realm from approximately contemporary Hungary to Bulgaria, their rule ended around A.D. 800 after they were invaded by Charlemagne and his army.

The Avars left no written history, and their language is preserved only as occasional words in contemporaneous Latin and Greek texts. But half a dozen previous research studies in the past decade have attempted to determine the origins of the Avar people through their DNA, ultimately finding considerable genetic influences from European, Eurasian and Northeast Asian populations.

Related: Largest-ever genetic family tree reconstructed for Neolithic people in France using ancient DNA

In the new study, the research team used software to calculate genetic relatedness from the DNA results. They found that most people were related to others in the same cemetery and that women's origins were more diverse than men's, suggesting that women married into the male-centered Avar culture. More specifically, women's parents were not found in the cemeteries, while men descended from the founding males of their family tree. Related individuals were almost always buried together.

"This suggests that Avar women left their homes to join their husbands' communities, which might have provided some social cohesion between distinct patrilineal clans," Lara Cassidy, a research assistant in the Department of Genetics at Trinity College Dublin who was not involved in the study, wrote in an accompanying News & Views article published in Nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The genetic analysis revealed that both men and women commonly had children with more than one partner. It also produced clear evidence for a practice called levirate, which is when closely related men have children with the same woman, often following the death of one of the men. The team found three pairs of fathers and sons, two pairs of brothers, and an uncle and nephew who each had shared a female partner.

"All the aforementioned phenomena lead us to assume that the segment of Avar society we investigated had a structure comparable to that of Eurasian pastoralist steppe people," particularly in terms of patrilineality or male-reckoned descent, the researchers wrote in their study.

By studying the specific lineages, or patrilines, the team also discovered that, in the large Rákóczifalva cemetery, there were shifts in genetics, food resources and grave types in the second half of the seventh century, suggesting a political transition as one patriline took power from another.

"This community replacement reflects both an archaeological and dietary shift that we discovered within the site itself, but also a large-scale archaeological transition that occurred throughout the Carpathian Basin," study co-first author Zsófia Rácz, an archaeologist at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, said in a statement.

Ultimately, the large-scale ancient-DNA analysis done in this study showcased the intricacies of Avar relationships, revealing that "the society maintained a detailed memory of its ancestry and knew who its biological relatives were over generations," co-first author Guido Alberto Gnecchi-Ruscone, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, said in the statement.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus