Methane Rising As Funding Cuts Threaten Monitoring Network

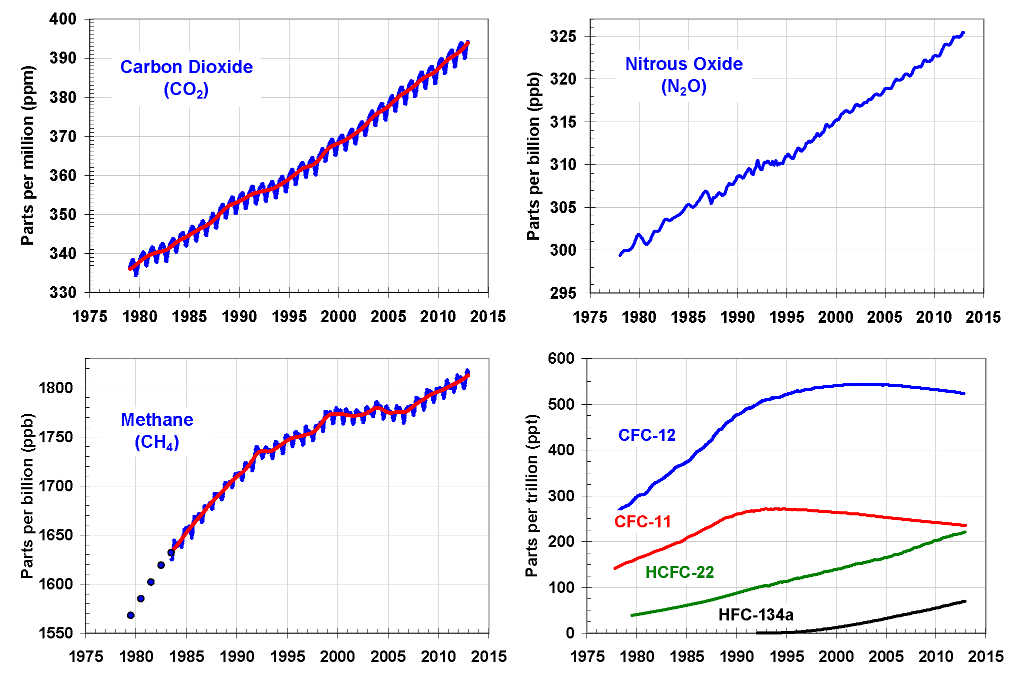

Levels of methane, a climate-changing greenhouse gas, have been rising since 2007. But U.S. federal budget woes are shrinking the monitoring network that tracks greenhouse gases such as methane, which comes from sources as varied as fracking and cow farts.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitors many potent greenhouse gases, such as methane, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, at observatories around the world. In the past six years, funding for part of the network — the collection of air samples in flasks — has not kept pace with cost increases, said Ed Dlugokencky, an atmospheric chemist with NOAA's Earth Sciences Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colo.

"We've had about a 25 percent decrease in the number of air samples measured from the global cooperative network," Dlugokencky told Live Science. "If we want to understand what is happening [with methane], we're going in the wrong direction to do that."

Invisible blanket

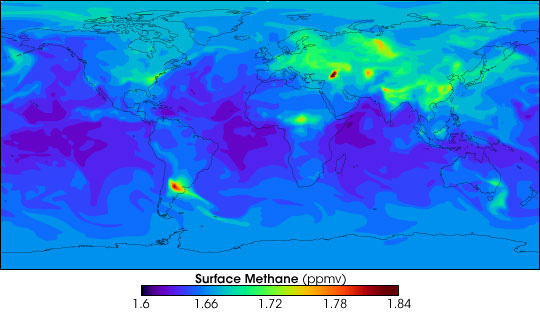

Methane gas lasts just nine years in Earth's atmosphere but is about 34 times more potent at trapping infrared radiation (the greenhouse effect) than carbon dioxide, which is more abundant and lasts longer. Methane levels in the atmosphere have doubled in the past 200 years. The growth rate slowed in 1991, (which Dlugokencky attributes to the fall of the Soviet Union and subsequent drop in industrial pollution), then resumed its strong rise in 2007, likely due to increased tropical wetlands emissions. The recent string of La Niña years has meant more rainfall in the tropics, leading to more methane, Dlugokencky said. Methane-producing bacteria in wetlands thrive when there's more water. [Greenhouse Gases: The Biggest Emitters (Infographic)]

One mystery in the global methane record is why Asia's strong economic growth, which includes a sharp uptick in methane-belching power plants starting around 2000, doesn't show up, Dlugokencky said. Global methane levels were fairly flat between 1999 and 2006.

While methane measurements on a global scale are now accurate down to a fraction of a percent, adding more sampling sites to the network could help researchers better understand what's happening to emissions on a regional scale, such as in Asia and the United States, according to an overview of the scientific challenges surrounding methane emissions published in the Jan. 31 issue of the journal Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We can pretty much tell what's happening at a global level, but if we want to understand what's happening in different regions, we really need to have a denser measurement network and a combination of different approaches, like aircraft and tall towers," said Dlugokencky, a co-author of the Science paper.

Gases rise, measurements decline

NOAA complements its air-sample measurements with continuous measurements at six observatories — in Hawaii, Alaska, Greenland, Antarctica, American Samoa and California — and tall towers throughout the United States. The agency also tracks greenhouse gases by plane, and other countries contribute to the network.

In 2012, NOAA's climate-monitoring budget woes prompted more than 50 scientists to publish a letter in Science warning that shrinking networks would harm long-term efforts to understand and track greenhouse gases. NOAA spends about $6 million each year on the program. As a result of funding cuts, in 2012, the agency slashed some monitoring from aircraft and ground stations.

The U.S. monitoring network is the main player in measuring global methane, Dlugokencky said. Yet the network's decline comes as methane is becoming a major climate concern.

Here are some examples:

Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing operations, by the oil and gas industries can emit significant amounts of methane. But no one knows how much methane escapes, nor its potential effect on regional or global temperatures. Some studies conducted in the United States suggest that fracking may be adding to methane emissions, but others indicate that there is less methane leaking than expected.

The warming Arctic could add significant amounts of methane gas to the atmosphere as permafrost melts and releases huge quantities of gas trapped in previously frozen ground. While some studies indicate methane may already be escaping from the Arctic ground, atmospheric levels of methane in the Arctic have not increased yet, Dlugokencky said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus