Artificial Bone Marrow Could Be Used to Treat Leukemia

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

For decades, doctors have been treating leukemia patients by transplanting stem cells from people with healthy bone marrow. But even though transplants can be a fairly effective treatment, there aren't enough tissue donors to treat every leukemia patient.

Now, researchers are taking the first steps toward making bone marrow in a lab: They are growing stem cells in a setting that mimics the natural environment of bone marrow.

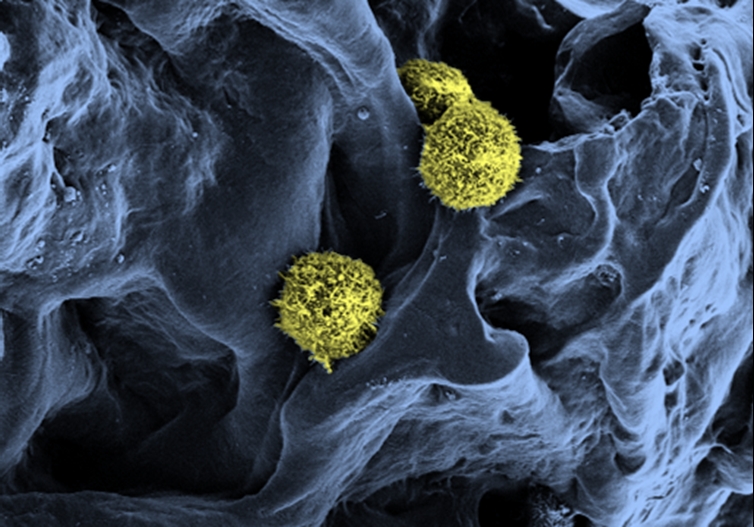

Leukemia is a cancer that starts in the bone marrow, the soft tissue inside bones that produces blood cells. The researchers' goal is to create artificial bone marrow that is capable of growing blood stem cells outside the body, said study researcher Cornelia Lee-Thedieck, of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in Germany. Such stem cells could then be used to treat leukemia patients.

But creating bone marrow in a lab isn't easy. "Bone marrow is very complex, with many, many different cell types, molecules, proteins," Lee-Thedieck said. What's more, the stem cells that could be used to treat patients can only grow and keep their properties in an environment that closely mimics real human bone marrow. [5 Crazy Technologies That Are Revolutionizing Biotech]

In the new lab work, the researchers recreated the spongy structure of bone marrow by making a hydrogel (like the material used to make contact lenses) around salt crystals, and then removing the crystals to leave holes for the stem cells to grow inside. They then added proteins and cells that support stem cells. Finally, they injected stem cells taken from umbilical-cord blood.

Their work successfully produced hematopoietic stem cells, which are the cells within the marrow that give rise to all types of blood cells. The stem cells reproduced in the artificial bone marrow, and more than 90 percent of cells still had the markings of stem cells after four days, a sign they retained their ability to form any type of blood cell, according to the study, detailed online this month in the journal Biomaterials.

Next, the researchers hope to grow the cells in the artificial environment for longer periods, and find ways to retrieve the cells from their scaffold. They also hope to "get a deep understanding of how the cells are influenced by the 3D environment and the material itself," Lee-Thedieck told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This method of growing stem cells still needs to be refined and tested in both animals and clinical trials before being used in humans. The soonest this treatment could be ready is in 15 years, if all goes smoothly, Lee-Thedieck said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus