Identifying Danger Zones Could Help Prevent Sea-Turtle Deaths

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When ocean-dwelling leatherback turtles encounter fishing lines or nets, the results can be deadly for the large marine animals. To help protect these turtles, researchers have identified "hotspots" where some of these deadly encounters are likely occur in the Pacific Ocean.

Leatherback turtles, which weigh up to 2,000 lbs. (900 kilograms), don't have a solid shell. Instead, their shell is made of bones connected by cartilage and covered by leathery skin (hence their name), said James R. Spotila, a study researcher and an ecologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia who studies these and other sea turtles.

Leatherbacks spend much of their lives in the open oceans but nest on tropical beaches, where the females lay eggs in the sand.

Like other marine animals, these turtles are at risk of becoming entangled in fishing gear — a phenomenon known as bycatch. When the turtles encounter lines set by fishermen to catch tuna and swordfish, they may mistake the bait for a meal or, more likely, become accidentally entangled, said John Roe, the lead study author and a wildlife ecologist at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke.

Because turtles must breathe air, they drown while caught up in a line.

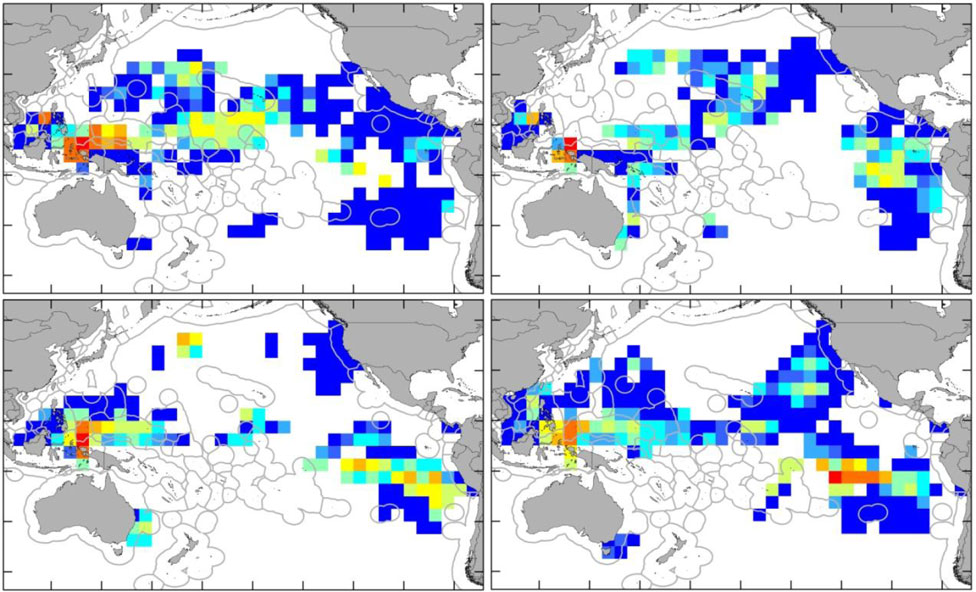

To identify potential hotspots for long-line-turtle encounters, the researchers combined satellite tracking information from 135 turtles with fisheries data. Roe and his colleagues calculated that, within the areas of the Pacific Ocean where the transmitter-toting leatherbacks traveled between 1992 and 2008, fishermen set an average of 760 million hooks per year. Other fishing gear, such as gill and trawl nets, also pose a risk to leatherbacks.

"Long lines are not the only problem, but it is the one we decided to focus on because we had data," Roe said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They drew on statistics collected by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization on hooks set and the weight of fish caught in the Pacific Ocean. Leatherback turtles are found around the globe; however, this study focused on the Pacific.

"Those in the Pacific have experienced the steepest decline of all the ones we have adequate data to assess," Roe said. "Some of [these populations] have almost completely blinked out of existence."

The team looked not only at location, but also season.

In the western Pacific, the researchers found unrelenting risk of bycatch near leatherbacks' nesting beaches on the island of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. This was one of the most concentrated areas of likely turtle-fishery interaction, Spotila said.

In the eastern Pacific, they found the greatest risk in the South Pacific Gyre, an expansive rotating current west of South America. The risk was most intense here between July and December.

The researchers hope that, ultimately, their work will help protect the turtles.

"Instead of looking out across the whole Pacific, now we can take these identified hotspots and times, and we can hone down that intractable problem into a smaller series of problems," Roe said.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+. Originally published on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus