Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 11:40 a.m. E.T. on Jan. 24.

The mystery of an ancient battle between two warring troops of elephants has been solved, thanks to a modern genetic analysis of the lumbering beasts.

Researchers have now found that Eritrean elephants, which live in the northeastern portion of Africa, are savanna elephants, and are not related to the more diminutive forest elephants that live in the jungles of central Africa.

That, in turn, discounts an ancient Greek account of how a battle between two warring empires played out, with one side's elephants refusing to fight and running away, the scientists report in the January issue of the journal of Heredity. [10 Epic Battles That Changed the Course of History]

Ancient battle

In the third century B.C., the Greek historian Polybius described the epic Battle of Raphia, which took place around 217 B.C. in what is now the Gaza Strip, as part of the Syrian Wars. During these wars, Seleucid ruler Antiochus III the Great fought against Ptolemy IV Philopator, the fourth ruler of the Ptolemaic Dynasty in Egypt, whose last leader was Cleopatra. The matchup included tens of thousands of troops, thousands of cavalry and dozens of war elephants on each side.

The elephants were the "ace in the hole," able to trample the enemy and sow terror with their massive size.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Elephants were considered the tanks of the time, until eventually the Romans figured out how to defeat war elephants," in later times, said study co-author Alfred Roca, an animal scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Antiochus had easy access to Asian elephants from India, but Ptolemy didn't. Instead, he set up outposts in what is now modern-day Eritrea to get African elephants.

Unfortunately, that strategy didn't work out so well: According to Polybius' account, the African elephants turned tail and ran when they saw how gigantic the Asian elephants were. Ptolemy, however, was able to recover due to missteps by Antiochus and eventually won the battle.

African elephants

In reality, Asian elephants are smaller than African elephants, so some historians speculated that perhaps the Ptolemies were using African forest elephants, which tend to be smaller, Roca said.

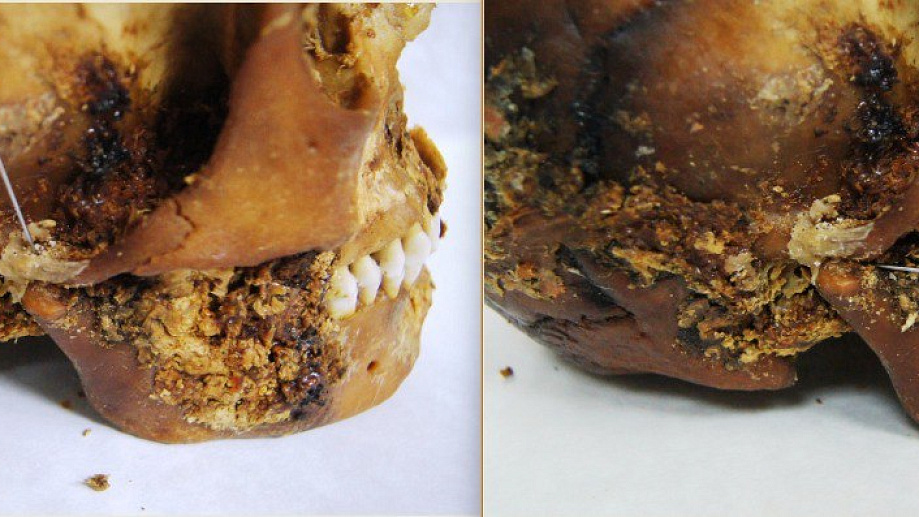

So Roca and his colleagues conducted a thorough genetic analysis of the elephants found in Eritrea, the descendants of the losers in the ancient battle.

"We showed using pretty much every genetic marker, that they were savanna elephants," Roca told LiveScience. "This was contrary to some speculation that there may be forest elephants present in that part of the world."

The team also found that there were just 100 to 200 African elephants left in isolated pockets in Eritrea, which could make them susceptible to inbreeding in the future.

Ancient myths

The findings suggest that Polybius had it wrong, and the African elephants got spooked for some other reason than the overpowering size of the Asian elephants.

In other ancient documents, "There were these ancient semi-mythical accounts of India, and they claimed that India had the biggest elephants in the world," Roca said.

Polybius, who wasn't actually at the battle, likely read those accounts and surmised the Asian elephants' bigger size caused their opponents to panic.

In fact, until about the 1700s, when scientists actually measured the two, most people still thought Asian elephants were the larger species, Roca said. (And even now, games such as Age of Empires that recreate the Battle of Raphia depict the Ptolemaic elephants as smaller.)

Editor's Note: This article was corrected to note that there are 100 to 200 African, not Asian elephants in Eritrea.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus