Ten Tiny Places That Have Their Own Domain Names

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Claiming to be a country is an easy task. But to make others to accept your claim is a lot harder. Aspiring states need favours from great powers, or sometimes even celebrities, to establish their legitimacy. In the digital age, this starts with wanting a top-level domain name, such as the “.in” suffix for India.

The Scottish National Party, which is rooting for Scotland’s separation from the UK in a referendum to be held this year, launched a campaign in 2008 to get Scotland its own top-level domain name. After five years, the International Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a consortium that controls these suffixes, agreed to setup the “.scot” suffix.

As Nina Caspersen, who studies the politics of unrecognised states at the University of York, wrote on The Conversation this week, states such as Somaliland and Transnistria start by setting up websites where they claim to be “independent and democratic”. However, with websites ending in “.com” or “.org”, respectively, their claims look weak.

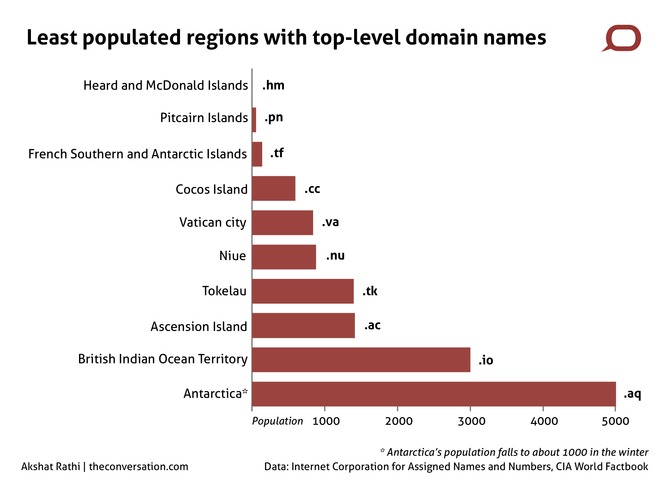

These countries would have had better luck had they been dependent regions to start with, because ICANN assigns domain names to dependent regions if they apply. That is why, although there are the 206 sovereign states (of which 11 are not recognised by the United Nations), there are 255 country-code domain names.

This can go too far. For example, Heard and McDonald Islands, a dependency of Australia in the Indian Ocean, has its own top-level domain name, “.hm”, even though its population is zero, and its official website uses Antarctica’s top-level domain name, “.aq”. It is also not alone.

Here is a list of the ten least populated regions with their own top-level domain name:

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

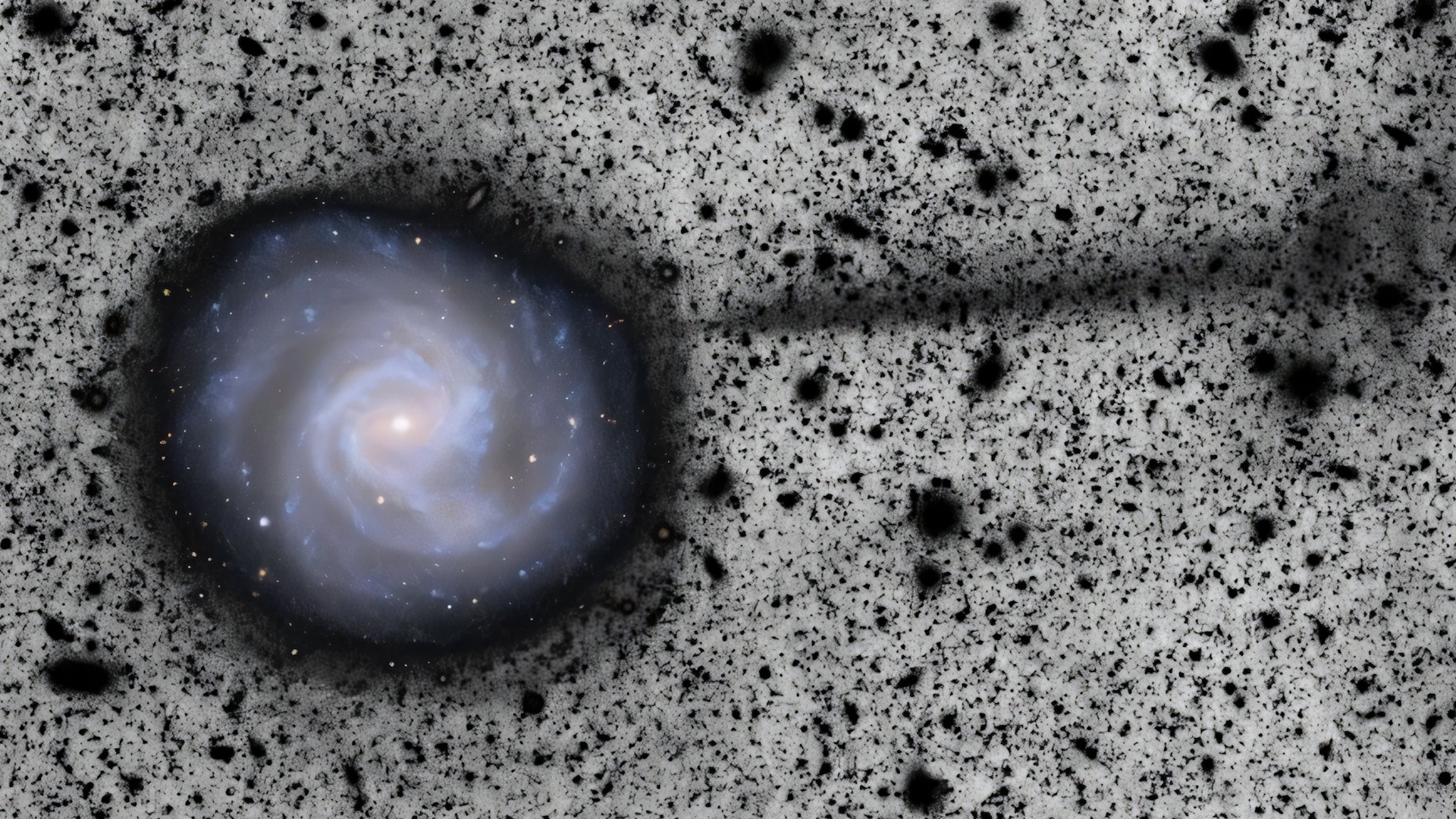

And because you’ll want to know exactly where they are, here’s a map:

Related: The politics of getting online in countries that don’t exist

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.