What Lives in Antarctica's Buried Lake?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

SAN FRANCISCO — A thriving community of single-celled microbes that consume carbon dioxide for food populate Antarctica's glacial Lake Whillans, the shallow lake buried under thousands of feet of ice, a researcher said here today (Dec. 10) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Water sampled from Lake Whillans in January 2013 is dominated by a dozen species of Archaea chemoautotrophs — mainly organisms that eat carbon dioxide, iron, sulfur and ammonia for energy, said John Priscu, a biologist at Montana State University who led the Lake Whillans microbiology team. Other singled-celled creatures included heterotrophs, species that munch the carbon discarded by their neighbors, the chemoautotrophs. Researchers are still analyzing the water samples for the presence of microscopic animal cells — the eukaryotes, Priscu said.

"This is still a work in progress," he said.

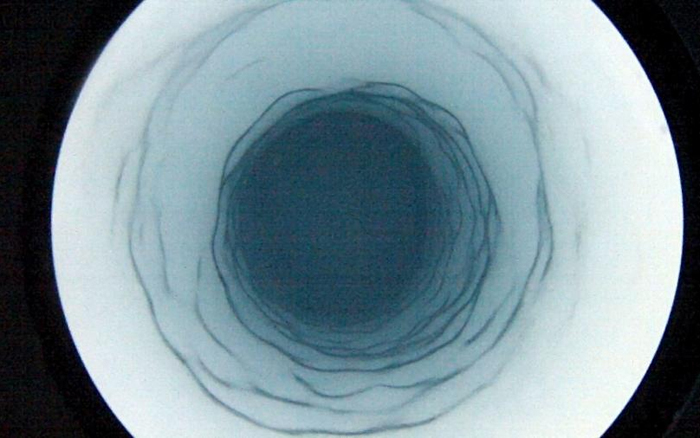

In January, drillers broke through Lake Whillans' surface and carefully brought uncontaminated water samples to the surface, after hauling more than a million pounds of equipment across Antarctica by tractor caravan. [Antarctic Album: Drilling Into Subglacial Lake Whillans]

Scientists have also discovered methane bubbling up into Whillans from the lake bottom — about 7.7 lbs. (3.5 kilograms) per day, Priscu said. Samples are being analyzed to see if the methane is newly produced, such as by bacteria, or is relic gas from ancient sediments. The research team also uncovered a mystery: sediment samples from beneath the lake bottom grew increasingly salty as the drill core went deeper.

"We've never seen this kind of a salt concentration before," even in exposed Antarctic lakes once covered by the ocean, Priscu said.

New analysis of the lake's sediments and historic water levels also suggest the microscopic life-forms live in an active waterway that may not have existed a decade ago, Priscu said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lake Whillans lies beneath 2,625 feet (800 meters) of ice in West Antarctica. Water has filled and drained the basin twice since 2006, Priscu said. (Scientists can track these changes because the lake raises and lowers the overlying ice when its water level shifts.) Because there are no hints of lake level fluctuations before 2004, Lake Whillans may not have even existed before then, Priscu said.

"Subglacial Lake Whillans is probably less than a few decades old," he said.

The Whillans drill team had planned to sample the lake again this Antarctic summer (2013-2014), as well as downstream where the water drains into the ocean, but both projects were cut by the National Science Foundation because of the government shutdown.

"Hopefully we'll get down there again," Priscu said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus