Swift Record! Migrating Birds Fly Nonstop for 6 Months

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have long suspected that the Alpine swift — a swallowlike bird that has a wingspan of about 22 inches (57 centimeters) and a body length of about 8 inches (20 cm) – spends much of its life in flight, based on field observations and radar data collected during its migration. But, until now, researchers have not been able to prove just how long these birds fly without taking a rest.

Researchers at the Swiss Ornithological Institute and the Bern University of Applied Sciences in Burgdorf, Switzerland, have collected data showing that the birds take little to no breaks during their migration from breeding grounds in Switzerland to wintering grounds in Western Africa and back again the following year. The team details their findings today (Oct. 8) in the journal Nature Communications. [Quest for Survival: Incredible Animal Migrations]

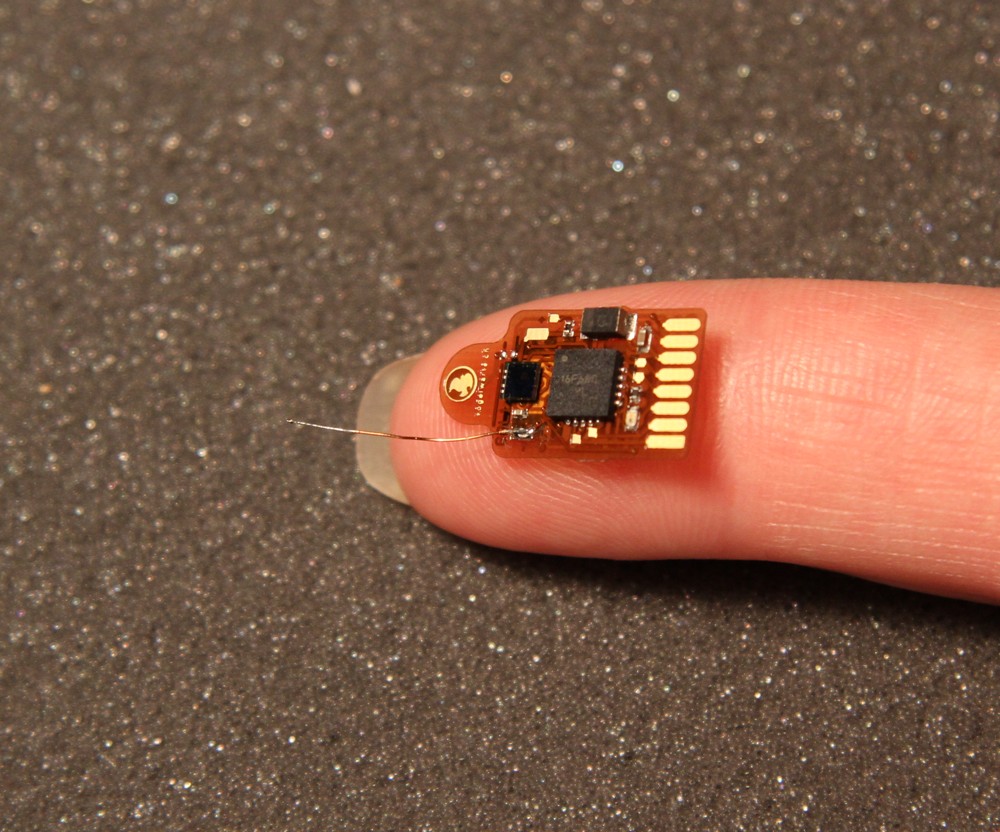

To collect their data, the researchers outfitted six birds with small tags that logged acceleration and ambient light during the course of a yearlong migration cycle that began and ended in Switzerland. Only three of the six birds were recaptured the following year, but these individuals provided enough data to complete the study, the researchers said.

The team analyzed the acceleration patterns captured by the loggers to determine when the birds vigorously flapped their wings, when they glided and when they rested.

The only period of sustained resting appeared during the breeding period in Switzerland. The birds appeared to glide and flap throughout their entire migration across the Sahara Desert and their overwintering period in sub-Saharan West Africa.

"Their activity pattern reveals that they can stay airborne continuously throughout their nonbreeding period in Africa and must be able to recover while airborne," the team writes in the report. "To date, such long-lasting locomotive activities had been reported only for animals living in the sea."

Migrating sea animals, including a variety of whale and fish species, expend less energy migrating than birds do because the swimmers rely partially on their own buoyancy to help keep them afloat.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Birds expend lots of energy during flight, but Alpine swifts do not need to stop to eatbecause they feed midair on what is called aerial plankton — the atmospheric equivalent to marine plankton that can include an array of tiny bacteria, fungus, seeds, spores and small insects that get caught in air currents.

Whether or not the birds sleep in flight remains unclear, though periods of decreased movement suggest that they do, indeed, catch up on a bit of rest midair. Still, the clear lack of significant resting periods suggest that the birds do not need as much sleep to perform their migration as previous research has suggested.

"We cannot rule out that the Alpine swifts may interrupt their flight for a few minutes," the team writes. "Nevertheless, they must be able to accomplish all vital physiological functions in flight over a period of several months."

The team next hopes to determine the evolutionary drivers responsible for what they consider to be an extraordinary behavior.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow LiveScience on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus