Newfound Mount Zion 'Mansion' May Hold Clues to Jesus' Jerusalem

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

During new excavations at Jerusalem's storied Mount Zion, archaeologists uncovered the remains of a possible mansion that's 2,000 years old. The dig leaders think the building and its contents could shed light on the wealthy class of Jerusalem during Jesus' day.

Artifacts and other clues suggest the mansion may have been the home of an elite Jewish family during the early Roman period, the researchers said. The building would have been located close to the expansive complex of Herod the Great, and inside, excavators found traces of an exceptional bathroom and the shells of sea snails that were valued for their rich purple dye.

"If this turns out to be the priestly residence of a wealthy first-century Jewish family, it immediately connects not just to the elite of Jerusalem — the aristocrats, the rich and famous of that day — but to Jesus himself," James Tabor, the dig's co-director, said in a statement. [Proof of Jesus Christ? 7 Pieces of Evidence Debated]

The archaeological finds could add to knowledge about this elite class that researchers have gleaned from the Bible, as well as the writings of Titus Flavius Josephus and later rabbinical texts.

"Jesus, in fact, criticizes the wealth of this class," added Tabor, who is a scholar of early Christian history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. "He talks about their clothing and their long robes and their finery, and, in a sense, pokes fun at it. So for us to get closer to understanding that — to supplement the text — it could be really fascinating."

Inside the building, the researchers discovered a vaulted bath chamber next to an underground ritual cleansing pool called a mikveh — an arrangement that has been found elsewhere within elite complexes. Archaeologists previously uncovered a nearly identical mikveh-bathroom combination while digging up a palatial mansion in the nearby Jewish Quarter. That complex bore the inscription of a priestly Jewish family.

"It is only a stone's throw away, and I wouldn't hesitate to say that the people who made that bathroom probably were the same ones who made this one," archaeologist Shimon Gibson, the other co-director of the dig, said in a statement. "It's almost identical, not only in the way it's made, but also in the finishing touches, like the edge of the bath itself."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

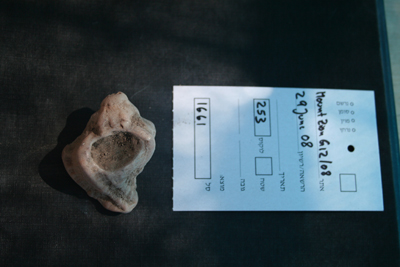

Another clue to the occupants' high status was a huge hoard of murex shells unearthed in the building. Murex sea snails were the source of an expensive and highly prized natural purple dye that could be extracted from the living animal's secretions.

Though the shells themselves were not used to make the royal purple dye, they may have been used to identify different grades of the stain, which could vary between sea snail species. Gibson speculates the priestly class may have supervised the industry that supplied the rich dye for ritual garments.

The artifacts were discovered this past summer, during a month-long dig, and the findings have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. The team expects to return to the site during the summers of 2014 and 2015. After their archaeological work is complete, the researchers hope the ruins will eventually be open to visitors.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus