Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

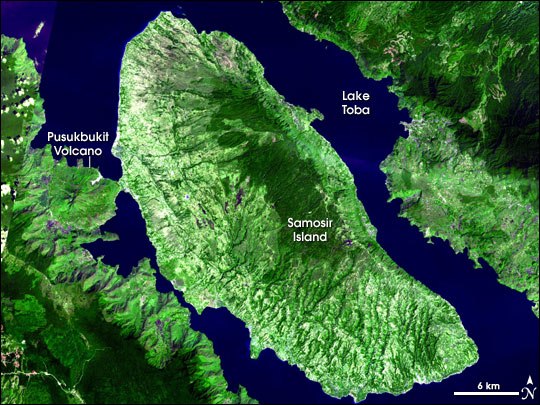

Humans didn't enter the Indian subcontinent until after the massive eruption of Mount Toba in Sumatra nearly 75,000 years ago, new research suggests — overturning a previous idea that humans arrived much earlier.

The research, published today (June 10) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used a combination of archaeological and genetic data to suggest a new earliest possible date for the exodus from Africa to Asia.

The new data suggest humans left Africa to arrive in South Asia around 55,000 to 60,000 years ago — long after the Mount Toba supereruption 74,000 years ago. That contradicts some archaeologists' claims that modern humans have been living in the region for twice that long.

"The ash from the eruption, which was an absolutely huge eruption, blew across all of India and smothered the whole region in ash," said study co-author Martin Richards, an archaeogeneticist at the University of Huddersfield in the United Kingdom. "Modern humans weren't there when that happened. They arrived afterwards."

Early dates

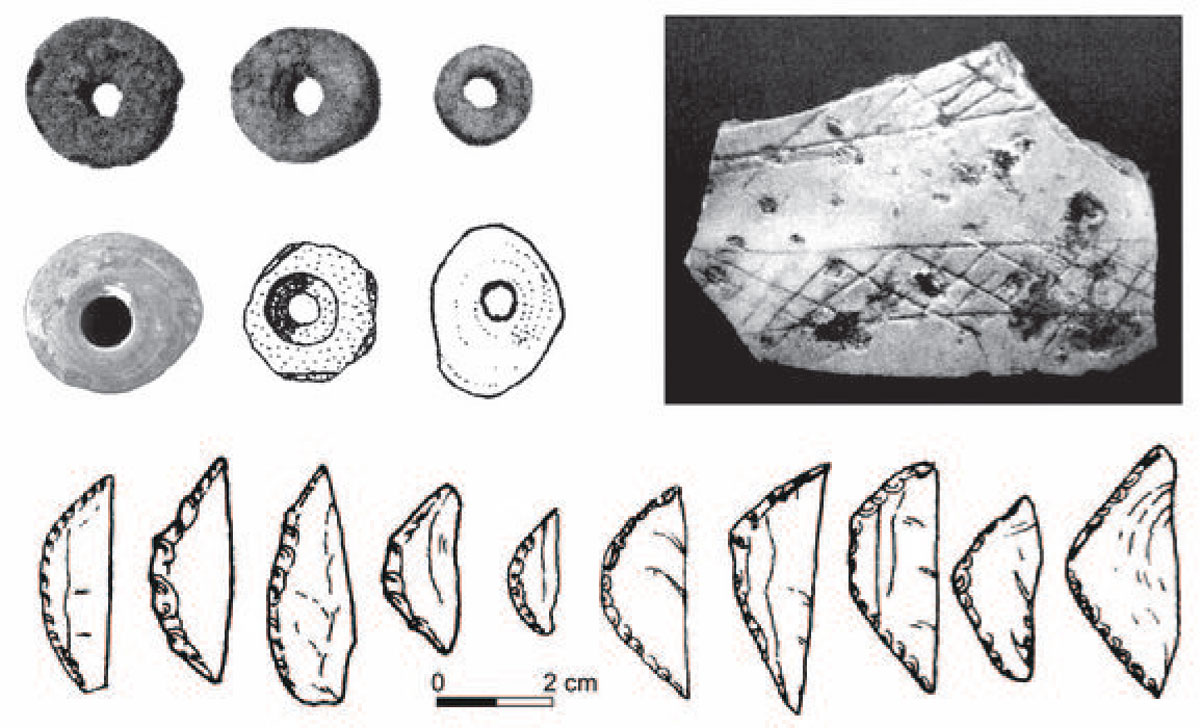

Most archaeologists believed humans migrated to what is now India between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago. However, in a 2007 study, archaeologists reported on stone tools unearthed in Jwalapuram in southeastern India both above and beneath the ash layer deposited by the Mount Toba supereruption about 74,000 years ago. That mega eruption spewed enough lava to create two Mount Everests and blocked sunlight for years. [10 Biggest Volcanic Eruptions in History]

One researcher argued that the tools looked similar to those used by modern humans in Africa at that time, which suggested that modern humans were in South Asia prior to the volcano eruption. Some even proposed that the migration might have happened as far back as 130,000 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To test the idea that humans reached South Asia before the eruption, Richards and his colleagues analyzed 817 samples of mitochondrial DNA, which is carried in the cytoplasm of the egg and is only passed on through the maternal line, from people throughout the subcontinent. They then compared it with existing samples from East Asia, the Near East and sub-Saharan Africa.

The genetic evidence suggested that people emerged in the subcontinent via the western coast between 55,000 and 60,000 years ago, well after the eruption. These ancient humans appear to have colonized the coasts of the subcontinent first, and then spread into the interiors along rivers, Richards told LiveScience.

Separately, archaeologist Paul Mellars of the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom and his colleagues analyzed archaeological evidence from the region. They analyzed the stone tools in Jwalapuram and compared them with stone artifacts from both other regions in the subcontinent and Africa.

Not modern humans

The team concluded that the tools from before the eruption did not resemble those used in Africa during the same period and, therefore, weren't made by modern humans. Instead, archaic humans — possibly Neanderthals — probably made the tools, Mellars told LiveScience.

"This paper provides a persuasively argued case that the Out of Africa movement took place around 60,000 years ago — that is after the Toba eruption event," Jim Wilson, a population geneticist at the University of Edinburgh in the U.K., wrote in an email.

In addition, the team used two types of data: modern archaeology and the largest collection of mitochondrial DNA evidence to date, wrote Wilson, who was not involved in the study.

"The findings are important for understanding the history of all humanity, given that southern Asia is on the route from Africa to East Asia, Southeast Asia, Australasia and the Americas," Wilson told LiveScience.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience@livescience,Facebook &Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus