Chemotherapy 'Bomb' Developed in Cancer War

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

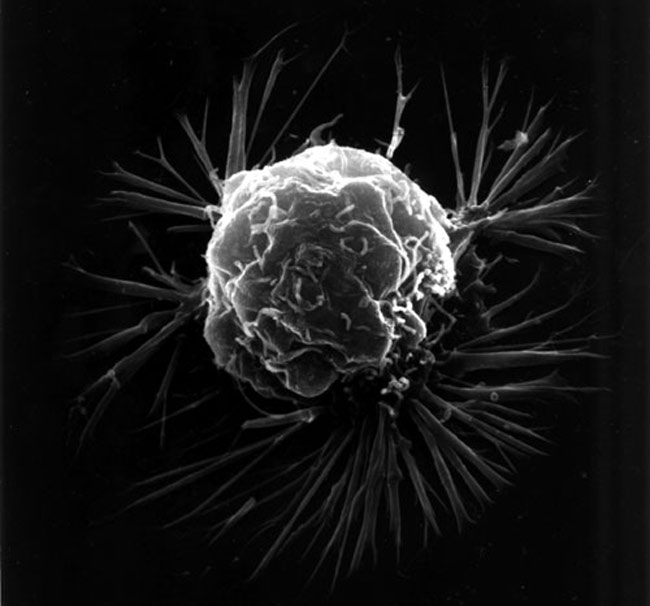

Scientists have developed a cancer drug that kills with James Bond stealth.

It breaks its way into a cancer cell, seals the exit, cuts off the cell's blood supply, and then detonates a chemotherapy bomb.

All that without harming healthy cells. Tests show the crafty drug has safely treated specific cancers and prolonged survival in mice.

"The fundamental challenges in cancer chemotherapy are its toxicity to healthy cells and drug resistance by cancer cells," said Ram Sasisekharan of MIT's Biological Engineering Division and leader of the research team.

The new technique uses nanoparticles to create what scientists call a vascular shutdown.

"Once the supply lines are cut off, these nanoparticles are trapped in the tumor and you can unleash the chemotherapy agent," Sasisekharan told LiveScience. "These cells die and collapse."

This technique is detailed in the July 28 issue of Nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

How it works

The researchers designed the drug based on the popular theory that if the blood vessels that supply blood to a tumor are destroyed, the tumor will eventually starve to death.

But cutting off the blood supply raises two other problems. First, the tumor will get hungry and undergo angiogenesis, the process in which the tumor branches out new vessels to find blood.

Secondly, chemotherapy is needed to fully kill the tumor, but "you can't deliver chemotherapy to the tumors if you have destroyed the vessels that take it there," Sasisekharan said.

Knowing this, Sasisekharan and his group designed a drug that would both stop angiogenesis and supply chemotherapy.

Using drugs that were already available, they created a nanoparticle that is layered like a Tootsie Pop -- the candy shell delivers an anti-angiogenic drug while the candy center is made up of a chemotherapeutic drug.

Once inside the cell, the anti-angiogenic outer layer quickly begins to dissolve, cutting off the blood supply and trapping the particle inside the cell. Next, the inner layer slowly releases a chemotherapeutic drug, killing the cell from the inside out.

"It's an elegant technique for attacking the two compartments of a tumor, its vascular system and the cancer cells," said Judah Folkman of Children's Hospital Boston.

Getting in

The particle combines stealth and small size to invade the tumor cell. The outermost surface of the nanoparticle has surface chemistry that tricks the tumor. The particle's small size allows it to easily pass through the tumor's pores.

Although the particle is tiny -- about 500 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair -- it is too large to squeeze into healthy cells. This ensures that only tumor cells, which have larger pores than healthy cells, are killed.

The engineered nanoparticle has so far proven to shrink tumors in mice, but what really excites researchers is the survival rate of the test subjects, especially compared to other current treatments.

Of the mice treated with the nanoparticle drug, 80 percent survived beyond 65 days. Mice treated with the best available existing therapy survived only to 30 days and untreated mice died at 20 days.

In a telephone interview, Sasisekharan said his team is currently screening human cell lines to test the drugs on. Human trials are a ways off.

"Depending on how things come together, I hope in a few years that we'll be there," he said.

- Tiny Capsules for Drug Delivery

- Cancer Takes Over Top Spot as Killer of Americans Under 85

- High-tech Probes Sneak Inside Your Cells

- Panel Affirms Radiation Link to Cancer

Small Stuff

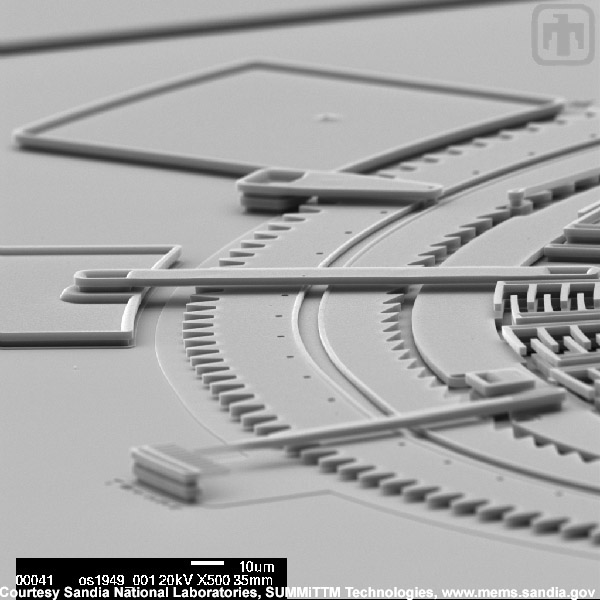

Micromachines

Microscopic Art

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus