Antarctic Ice Collapse Fuels 'Mind-Boggling' Melt

A familiar philosophical question about trees and forests might be applied to events in the world's loneliest spot: If an ice shelf collapses in Antarctica, and there's nobody around to hear it, does it make a sound?

If a satellite is watching, then the answer is yes.

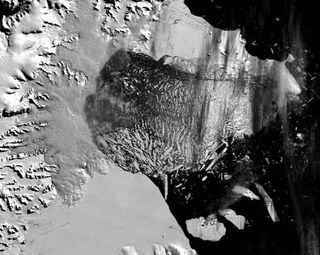

In 2002, the Larsen B ice shelf, a vast, floating plain of ice larger than Rhode Island which had been there for as long as 12,000 years broke off from Antarctica's coastline, disintegrated into an army of icebergs and floated away in the course of 35 days. (Ice shelves are enormous plates of ice that float on polar seas but are connected to the shoreline by the land-bound glaciers that feed into them.)

A NASA satellite caught the dramatic events on camera. Years before, in 1995, a neighboring ice shelf, the Larsen A, also collapsed, but before the advent of technology capable of documenting its demise in such gory detail.

"The images that detailed the collapse of the Larsen B, that was a real newsmaker around the globe," said Christopher Shuman, a research scientist with the University of Maryland Baltimore County and NASA. Shuman was the lead author on one of the most detailed studies to ever quantify the aftereffects of ice shelf breakup specifically, what happened after Larsen A and Larsen B went missing.

It turns out that, like any bad breakup, it's the lingering effects that follow the big blow-out that can be the most painful.

Shuman and his colleagues on a new study found that when ice shelves break off, the glaciers back on the land that feed the massive floating rafts of ice suffer for years afterward. "The volume of the losses is much larger than people had been able to document before," Shuman told OurAmazingPlanet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Icy doorstops

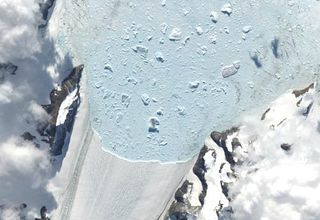

Ice shelves are formed by glaciers, which are akin to colossal, slow-motion rivers of ice. Just as rivers empty out into the sea, glaciers creep toward the ocean , pulled onward by gravity, and, as they reach the shore, glaciers "empty" out into ice shelves the mingled ends of glaciers, many hundreds of feet thick, formed over thousands of years.

Ice shelves cling to landmasses in the Earth's polar regions which include Greenland, parts of Canada and Antarctica and range from a few hundred miles across to one the size of Texas.

Scientist have found that ice shelves act as giant floating doorstops; when ice shelves disappear, the glaciers that push against them speed up. What they didn't know was just how much the glaciers sped up and how much ice they lost in the aftermath.

"The removal sets changes in motion, and they continue for many years, even decades, into the future," Shuman said.

'Mind-boggling' ice loss

To determine the answers to these questions, Shuman and his co-authors combined reams of Antarctic ice data collected by satellites and aircraft from 2001 to 2009.

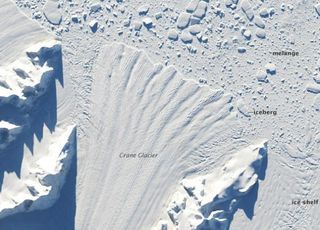

From 2001 to 2006, glaciers that were once buttressed by the Larsen A and B ice shelves lost 11.2 billion tons of ice per year, and about 10.2 billion tons per year in the four years following. During the study period, more than 14.5 cubic miles (60 cubic kilometers) of glacial ice melted into the ocean. [Album: Stunning Photos of Antarctic Ice]

One glacier, the Crane, experienced elevation loss of 300 feet (90 meters) in the space of just one year. "That's mind-boggling. You just try to imagine what it would have been like had you been standing on the glacier," Shuman said. "It would have almost felt like an elevator going down."

And although the overall volume of ice lost during the study period only negligibly contributes to sea level rise about 0.03 millimeters (about one-hundredth of an inch) per year Shuman said the effect is a harbinger of bigger things to come.

Warming times

"We suspect strongly that the sequence of events that we're documenting for these smaller ice shelves and glaciers will be repeated in the future for the larger ice shelves and their supporting glacier systems," Shuman said.

So far, those larger ice shelves are holding steady, though there's no guarantee on how long they'll be able to do so.

"Where the ice shelf was taken away, the glaciers are losing hundreds of feet of elevation a year, and the area just south of it is showing almost no change. The only thing that is different is the ice shelf hasn't disintegrated yet," said Ted Scambos, a co-author on the study, and lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, at the University of Colorado, in Boulder.

Both scientists said that warming seas and warming air temperatures mean that ice shelves can't re-form in the areas where they once stood. In addition, the warming effect is marching farther and farther south into Antarctica, weakening more ice shelves as it goes.

Scambos said the spectacular demise of the Larsen B illustrated the unpredictability of global warming's effects on Earth's coldest regions.

"People assumed the ice shelf was doomed, but that it would take decades, not crumble away in the space of a few weeks," Scambos said.

"What we see is that the whole system is a whole lot more dynamic than we would have expected 15 or 20 years ago," he said. "To me, that indicates we're going to have a really tough time forecasting sea level rise in the future. It's going to take a lot of effort to track down how certain areas are going to change."

And, Scambos added, lack of attention to those changes isn't halting its progress.

"We're passing further thresholds in terms of mass loss," Scambos said. "This is not going to go away because we forgot to read about it."

- Photo Album: Antarctica, Iceberg Maker

- Earth in the Balance: 7 Crucial Tipping Points

- Gallery: An Expedition into Iceberg Alley

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.

Most Popular