Earth's Core Covered By Liquid Rock, Experiment Suggests

Oceans of magma may exist deep in the planet's interior, near where the Earth's mantle and core meet, researchers say.

Such magma oceans could be relics from the earliest days of the planet, when it might have been almost completely molten.

To reach their findings, scientists re-created the kind of pressure and heat one might find near the core.

Although the mantle beneath the Earth's crust which makes up nearly 85 percent of the planet's volume is searing hot, it remains solid (unlike the liquid rock that makes up lava on the surface and the magma under it). The crushing pressures deep inside the Earth keep the mantle from turning liquid, much as high pressure keeps liquid nitrogen from boiling into its gaseous form.

However, scientists have suspected for 15 years that the area of mantle near the top of the Earth's very hot core was partially molten. Sound generally passes through liquids more slowly than through solids, and seismologists have long noticed that seismic waves often slow down abruptly, losing up to a third of their speed or so, as they get close to where the mantle and core meet, which is roughly 1,800 miles (2,900 kilometers) down. These mysterious zones can be as thick as 30 miles (50 kilometers).

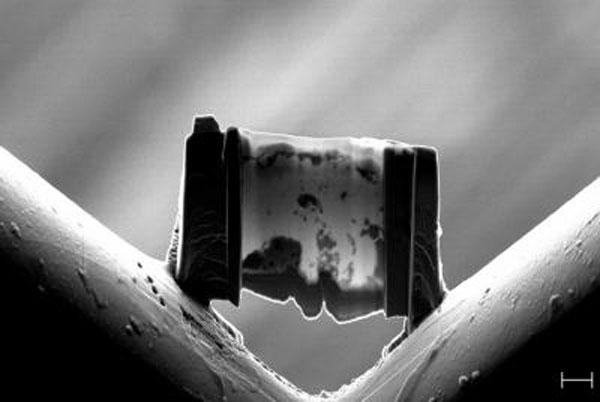

Researchers reported in the Sept. 17 issue of the journal Science that they took samples of peridotite the kind of rock often found in the mantle and squeezed them between diamonds, reaching a pressure of about 1.4 million times that of the atmospheric pressure at sea level. At the same time, they blasted the samples with infrared lasers, heating them to more than 8,540 degrees Fahrenheit (4,726 degrees Celsius).

The researchers discovered that at 7,100 degrees F (3,926 degrees C), the rock melted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The finding suggested that magma oceans exist atop the Earth's core.

They "could be some residual liquids formed very early in Earth's history, during the magma ocean state, which is a model telling us that the whole Earth could have been almost totally molten when it formed because of numerous collisions with asteroids and planet embryos," said researcher Guillaume Fiquet, a mineral physicist at Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris.