Plant Parts Release Sperm When Squeezed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When it comes to sex, plants and humans have more in common than one might think.

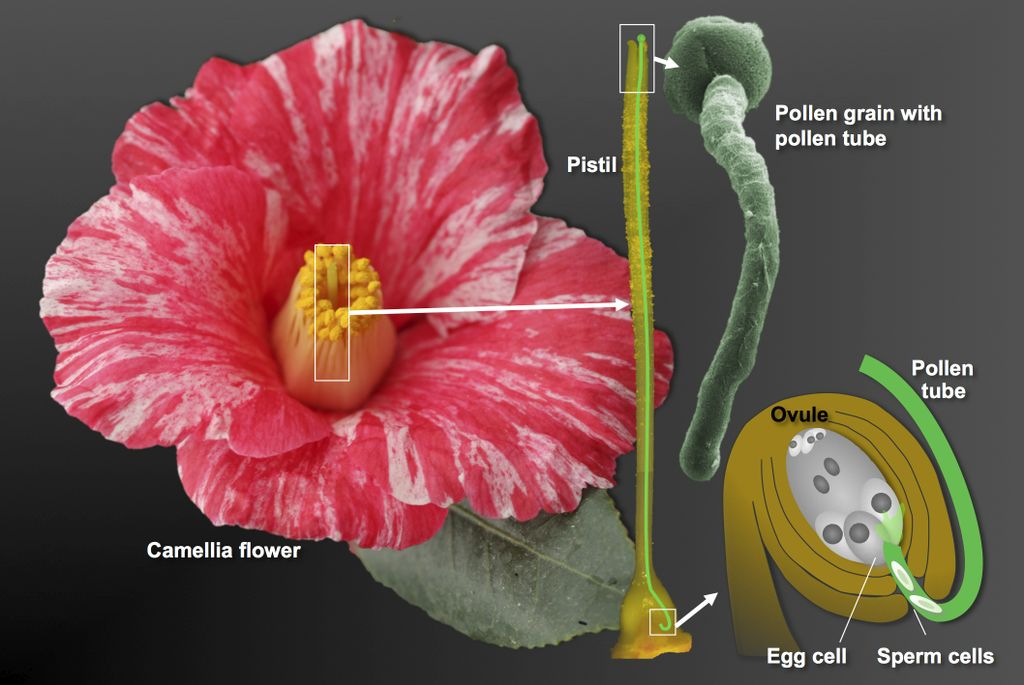

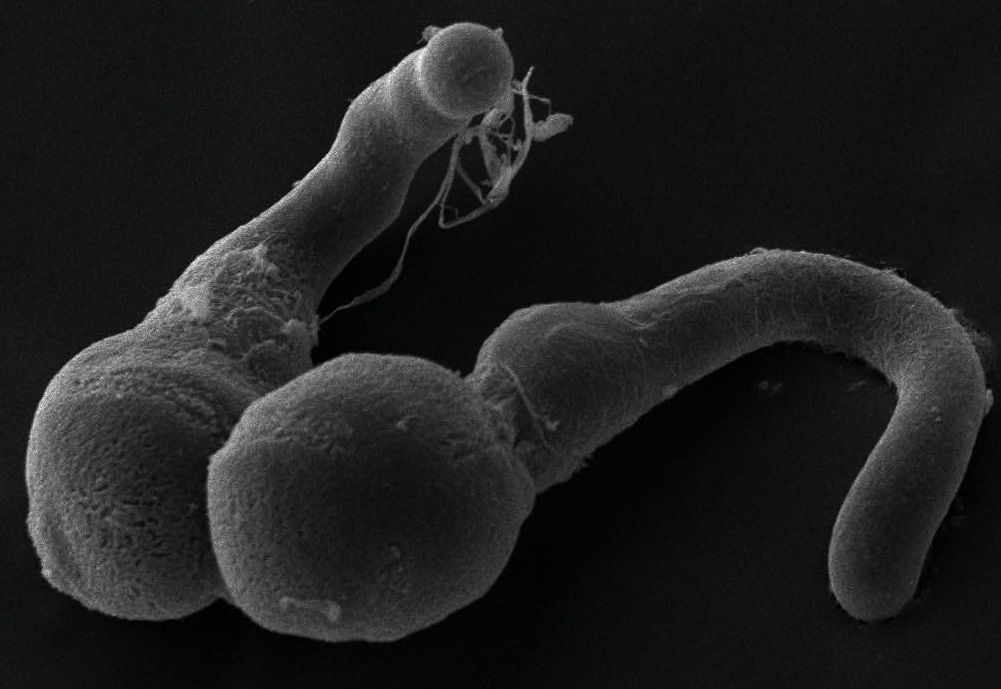

During plant reproduction, the male sex organ, called the pollen tube, grows in length as it plows through tissue on its way to the female organs. And when the tube encounters too tight a grip, it bursts and releases sperm, a new study reports.

But unlike its human equivalent, the pollen tube is a single cell. It's the fastest growing cell in the plant, and like all plant cells, it has a cell wall. As the tube — which contains the sperm cells — drills through the tissue of the female plant, the internal fluid pressure pushes out on these walls, keeping them rigid. [Gallery: Tantalizing Images of Plant Sex]

"It's essentially like a balloon that you blow up and it swells," said study co-author Anja Geitmann, a biologist at the University of Montreal in Canada. As it grows, the pollen tube encounters resistance from the cells of the surrounding tissue. "How does the tube actually generate the forces necessary to penetrate the cells?" Geitmann wanted to know.

To find out, the researchers developed a special chip to measure the forces a pollen tube encounters as it grows. They tested the growth of pollen tubes of the Japanese Camellia (Camellia japonica) in a microscopic obstacle course where they had to navigate a maze of narrow openings.

Because pollen tubes are so small — between 5 and 20 micrometers wide (less than a fifth the width of a human hair) — microsystems technology was required to measure the miniscule amount of force they exerted on their surroundings. The tube must maintain its shape as it creeps through the tissue, as any kinks or collapses would prevent the sperm from passing through freely.

The microscopic channels of the obstacle course were made of an elastic polymer material, and were made narrower than the width of the pollen tubes. By modeling how the material deformed as the pollen tubes passed through, scientists calculated that the tubes exerted a

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

pressure of at least 21.8 pounds per square inch (150 kiloPascal), about the pressure of a car tire.

When the channels were wider, the pollen tube passed through without deforming much. But when the opening was too narrow, the tubes simply burst — spewing their precious sperm cargo.

The parallel with human ejaculation is hard to avoid. The force by which the pollen tube stays upright is the same as the human penis, Geitmann said — "It's a hydroskeleton tube under pressure."

The findings were published today (April 29) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus