Fearsome Foursome of Eruptions Seen from Space

With more than 300 volcanoes crowded into a finger of land roughly the size of California, Russia's Kamchatka peninsula is home to the world's highest concentration of active volcanoes.

Only 29 volcanoes are active, occasionally spilling lava down their slopes or shooting steam and ash into the sky. On Jan. 11, NASA's Terra satellite snapped a picture of a fearsome foursome, as a quartet of Kamchatka's volcanoes erupted at the same time.

The four volcanoes — Shiveluch, Bezymianny, Tolbachik and Kizimen — are separated by only 110 miles (180 kilometers), according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

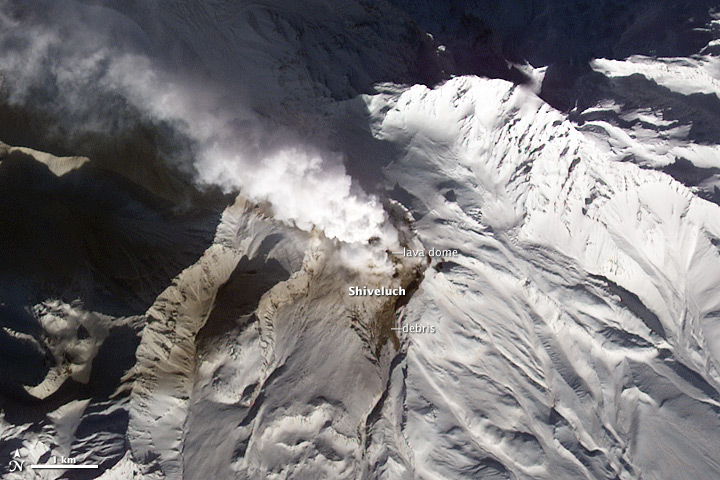

The eruption style varies among the volcanoes, the Earth Observatory noted. At Shiveluch and Bezymianny volcanoes, thick, pasty lava is forming a mound called a lava dome, similar to the caldera at Mount St. Helens in Washington.

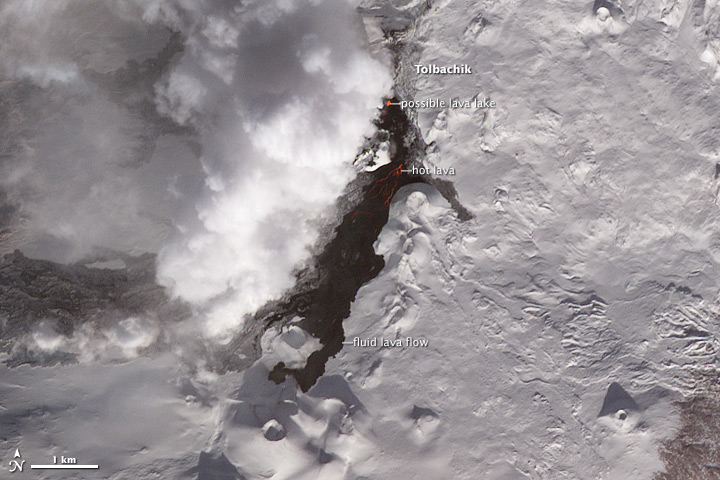

Further south, at Tolbachik volcano, thin, runny lava streams down the slopes of the volcano, forming low and broad flows similar to those at Hawaii's Kilauea volcano. Glowing hot lava is visible in the near-infrared light of the satellite image.

Finally, Kizimen’s lava is a mix: not as viscous and sticky as Shiveluch and Bezymianny, but not as fluid as Tolbachik's. The intermediate lava forms thick, blocky flows. The dark, fan-shaped deposits seen on the volcano are rocks and ash that fall from Kizimen's summit.

More than 100 volcanoes on the Kamchatka peninsula have erupted in the past 12,000 years. The land sits above a subduction zone, where two of Earth's tectonic plates meet and one slides beneath the other into the mantle, the deeper layer beneath the crust. As heat and pressure from the mantle squeeze water out of the lower plate, the water escapes. The water helps partially melt the nearby mantle, creating magma. The magma rises upward, drilling through the Earth's crust and, when it reaches the surface, eventually forming volcanoes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kamchatka's volcanic arc is one of several surrounding the Pacific Ocean, part of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.