West Antarctic Warming Doubles

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If there's a polar pity party, West Antarctica's just been added to the VIP list. The frigid expanse is now one of the fastest-warming spots on the planet.

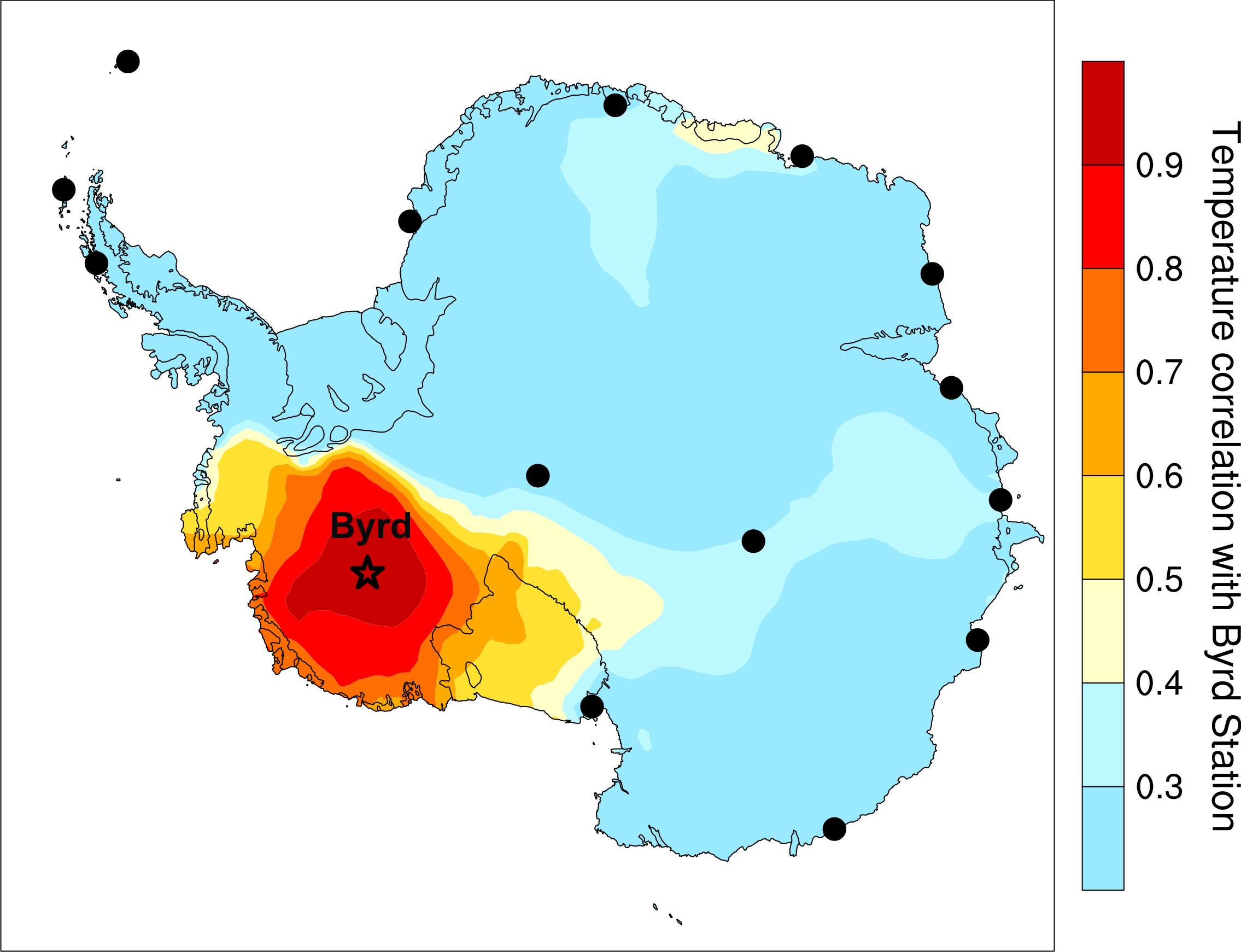

Temperatures at Byrd Station, an outpost on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, jumped by 4.3 degrees Fahrenheit (2.4 degrees Celsius) since 1958, researchers report today (Dec. 23) in the journal Nature Geosciences. The warming in West Antarctica is twice as large as previous estimates for the region, said David Bromwich, study author and a senior research scientist at the Byrd Polar Research Center at Ohio State University.

Although Byrd's average summer high still hovers around 14 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 10 degrees Celsius), the marked increase raises concerns that the ice shelf could destabilize through surface melting, as with Greenland's spectacular surface melt this July. The results also suggest that Antarctica has experienced the same rapid temperature shifts as polar regions like Greenland and the Canadian Arctic, a phenomenon called polar amplification, Bromwich said.

Article continues below"The changes taking place in Antarctica are as big as what's happening in the north," Bromwich told OurAmazingPlanet.

Monitoring changes

Scientists have known for several years that the Antarctic Peninsula, which curls out into the ocean toward South America, was warming rapidly. But the rest of Antarctica seemed shut out of the crowd, isolated from the effects of climate change. Byrd Station, sitting some 700 miles from the South Pole near the center of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, is an important indicator of climate change in continent's interior.

In the past, researchers haven't been able to make much use of the Byrd Station measurements because the data was incomplete; nearly one-third of the temperature observations were missing.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists had an excellent temperature record from the 1957-1969, when the station was monitored year-round by professional meteorologists. And the automatic weather stations installed after they left ran well on radioisotope generators — the same ones NASA used in its deep-space probes — because the radioactive decay helped heat the electronics. But the generators were removed in the 1980s, when Antarctica went nuclear-free. The automatic weather stations now run on buried car batteries, which are charged in the summer by solar panels. The weather stations now have frequent power outages, Bromwich said. [Video: Life on the Antarctic Ice]

Bromwich and two of his graduate students, along with colleagues from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, corrected past temperature measurements and filled in missing observations with a computer atmospheric model.

Summer surprise

The strongest warming occurred in the Antarctic spring, during September, October and November, said Ohio State University doctoral student Julien Nicolas, a study co-author. But the discovery of summer warming (in December, January, February) was a surprise, because previous studies had found no significant warming in other areas of Antarctica during the summer, Nicolas said.

"Summer was seen as a season with no significant temperature changes," he told OurAmazingPlanet. "This result is of concern because if the warming continues, it suggests that the melting could be happening more often and this could have an impact on the state of the West Antarctic ice sheet."

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet holds 10 percent of Antarctica's ice and is about the size of Greenland. The base of its glaciers sits below sea level, making melting a particular concern. Melting could destabilize the glaciers, leading to faster flow and increased sea level rise.

"This is really one of the regions we need to be watching with regard to climate change," said David Schneider, a polar climate scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, who was not involved in the study.

"Now that we have the station record, that will give us an idea of warming over Antarctica as a whole," Schneider told OurAmazingPlanet. "I think you will see those numbers are really important for climate modeling and how this is impacting the overall global temperature trends."

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus