Hurricane Sandy Moved Barrier Islands

Barrier islands pummeled by Hurricane Sandy shifted inland during the storm, a natural response to sea level rise, according to surveys conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey.

Barrier islands are ribbons of sand running parallel to the coast, both in the Atlantic Ocean and around the world. In the United States, the narrow islands have attracted intensive development, creating a conflict between the migrating islands and residents who want their dune-anchored homes to stay in place.

Fire Island, a barrier island off the southern coast of Long Island, N.Y., traveled 65 to 85 feet (19 to 25 meters) inland after Hurricane Sandy, said USGS coastal geologist Cheryl Hapke. The estimate comes from the island's dune, which eroded by that amount.

"The dune was largely destroyed, but where it remains intact, this will be the new position," Hapke told OurAmazingPlanet. "If the dune moves back 65 feet, it means the whole island also moved landward."

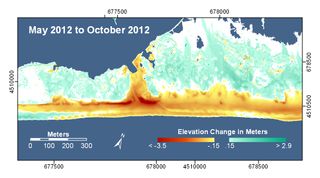

Fire Island is 31 miles (50 kilometers) long but ranges between only 520 and 1,300 feet (160 and 400 m) wide. During powerful storms like Hurricane Sandy, waves punch a hole the dune, bringing sand inland. On Fire Island, elevations on the beach dropped by as much as 10 feet (3.5 m), while inland areas gained about 3 feet (1 m) in height in places, said Hilary Stockdon, a USGS research oceanographer. The entire island was flooded and seawater breached the island in three places. Erosion from the surging waters exposed a long-buried shipwreck in the Fire Island National Seashore.

Barrier islands like Fire Island are moving closer to shore to maintain a constant elevation relative to sea level, Hapke said. "Barrier islands need to move landward to be able to survive sea level rise, and storms are the drivers for that," she said.

Fire island is a living laboratory for the USGS. Twenty percent is developed, with a community that manipulates and replenishes the natural sand system, and 80 percent is preserved as public land. "This is really going to be an invaluable contribution to our understanding of storms as drivers of coastal change," Hapke said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The USGS has spent a decade surveying the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coast to learn to predict storm damage. New surveys show 70 percent of the island is vulnerable to overwash (when waves and storm surge come over the protective dune), Stockdon said. Only 20 percent of the island was exposed to overwash before Sandy. And the nor'easter that plowed through in early November appeared to further erode the base of the dunes, Hapke said.

"The vulnerability is different than before Sandy made landfall, and this is the case for much of the coastline for North Carolina through New York," Stockdon said at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union earlier this month.

"It's challenging for communities who want to live on the beach, but we have to acknowledge that this is how barrier islands and beaches are going to respond to these big-wave events," Stockdon told OurAmazingPlanet. "As we move forward into planning these communities, we should keep the science of beaches and waves in minds."

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Most Popular