Sandy's Destruction Revealed in Aerial Scans

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

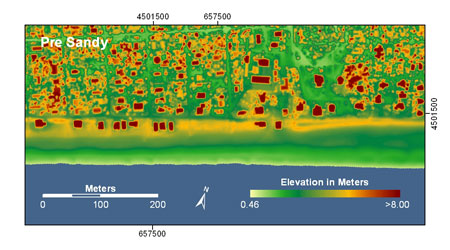

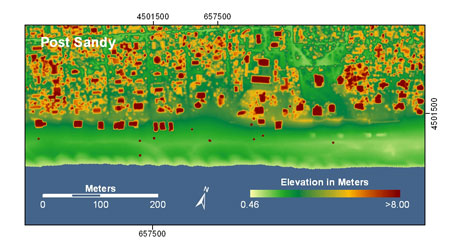

New before-and-after airborne laser scans of demolished dunes in Long Island, N.Y., reveal the extent of the destruction caused there by Hurricane Sandy.

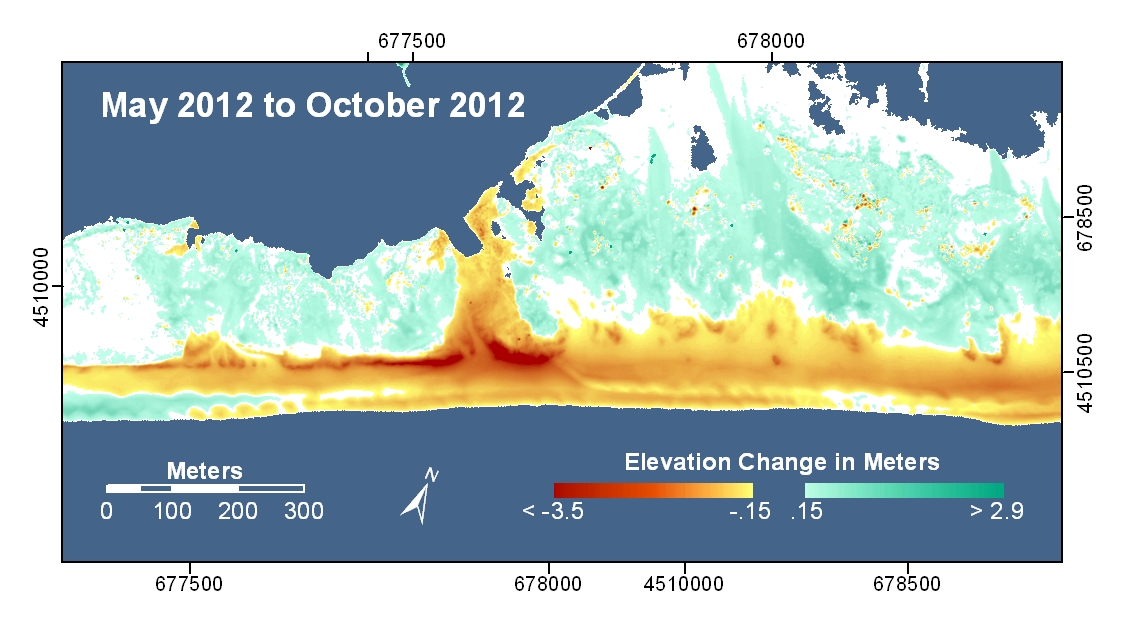

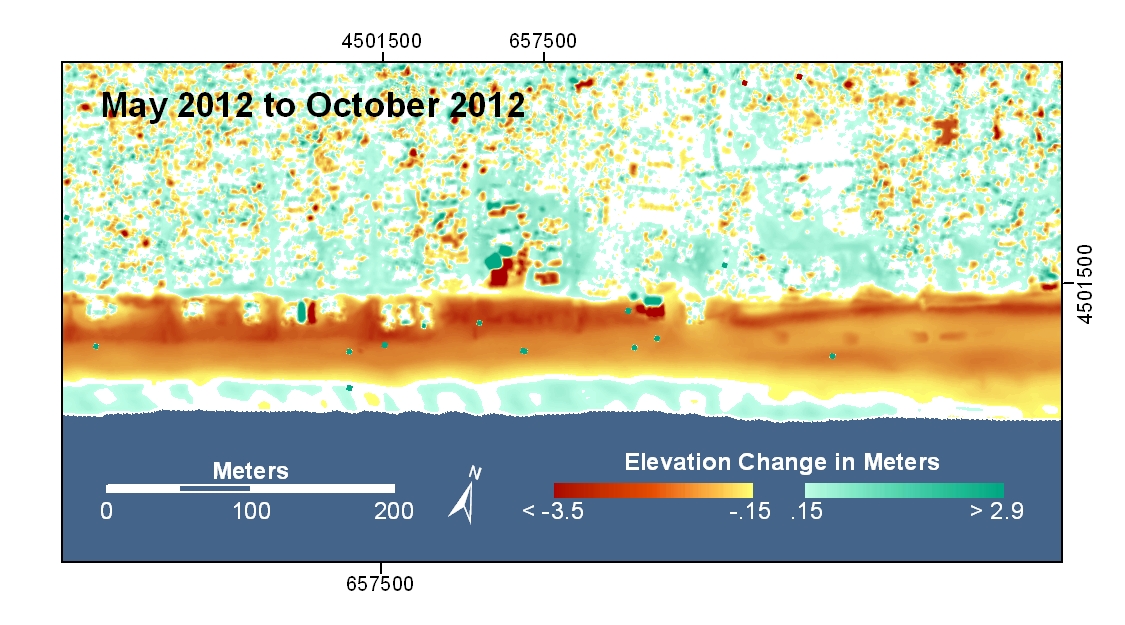

The images show that the storm dramatically reshaped Fire Island, a barrier island off the southern coast of Long Island. Within Fire Island National Seashore, the sea breached a narrow part of the island, creating a new inlet and cutting through 13-foot-high (4 meters) dunes. At Ocean Bay Park, where there were many homes near the water, the beach lost more than 10 feet (3.5 m) of dune during Hurricane Sandy.

At Ocean Bay Park, "You can see in the prestorm image a yellow line, that's the sand dune, and what's interesting is you can see houses that are sitting right on the sand dune," said Hilary Stockdon, a research oceanographer with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in St. Petersburg, Fla. "And in the post-storm elevation image, that yellow strip representing the high dune elevation is gone. The dune was completely washed away," Stockdon told OurAmazingPlanet.

Fire Island is 31 miles (50 kilometers) long but range between only 520 and 1,300 feet (160 and 400 m) wide. The entire island was flooded during Hurricane Sandy and seawater breached the island in four places.

Erosion from the surging waters exposed a long-buried shipwreck in the Fire Island National Seashore.

The laser scans are preliminary images released by the USGS. In the days following Hurricane Sandy, USGS scientists flew over coastal areas from North Carolina to New York to monitor changes, Stockdon said.

The USGS scanned beaches and islands with lidar, or light detection and ranging, which bounces a stream of laser pulses off the ground. Airborne lidar equipment can measure surface elevation to within a few inches.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The lidar data will help the USGS improve their future storm prediction modes in two ways: The USGS will use the lidar data to check the accuracy of their Hurricane Sandy storm predictions against what actually happened along the coast, Stockdon said. In addition, updating their records of current coastal topography is essential for future storm modeling, she said.

"It's very important to provide a picture of what the beach looks like now," Stockdon said. "Our models of how the beach was going to respond to Sandy were based on a time stamp of how those beaches looked in 2010. They had very fluffy, healthy dunes, and now those dunes are gone."

The USGS predicted extensive overwashing and breaching for Fire Island in advance of Hurricane Sandy, and New York ordered a mandatory evacuation for the island.

"Now those coastal communities are more vulnerable to future storms, and we can use these new elevations in our models to get a more accurate picture of how the beaches will respond to future storms," Stockdon said.

Reach Becky Oskin at boskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus