Tycho Brahe Died from Pee, Not Poison

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

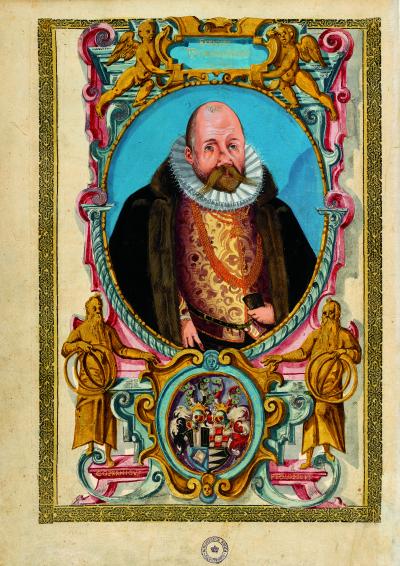

Two years after Tycho Brahe was exhumed from his grave in Prague, chemical analyses of his corpse show that mercury poisoning did not kill the prolific 16th-century astronomer. The results should put to bed rumors that Brahe was murdered when he most likely died of a burst bladder.

Separately, tests revealed that Brahe's famously "silver" prosthetic nose was actually made out of brass.

Born in Denmark in 1546, Brahe served as an astronomer for the Danish king before settling in Prague in the court of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II. Brahe is known for making the most accurate measurements of stars and planets without the aid of a telescope, proving that comets are objects in space and not in Earth's atmosphere, and hiring the not-yet-famous German astronomer Johannes Kepler as his assistant.

Brahe was long thought to have died from a bladder infection after politeness kept him from excusing himself to use the bathroom during a royal banquet in October 1601, causing his bladder to rupture. However, scientists who opened Brahe's grave in 1901 to mark the 300th anniversary of his death claimed to find mercury in his remains, fueling rumors that the astronomer was poisoned. Some even accused a jealous Kepler of the crime.

But the new results don't point to any such intrigue. While analyses of Brahe's teeth are not yet complete, tests on his bones and beard hairs show that mercury concentrations in his body were not high enough to have killed him, the team of Danish and Czech researchers said. Brahe's mercury levels even dropped to the low end of normal in the weeks leading up to his death, tests on Brahe's beard revealed.

"In fact, chemical analyses of the bones indicate that Tycho Brahe was not exposed to an abnormally high mercury load in the last five to ten years of his life," said researcher Kaare Lund Rasmussen, an associate professor of chemistry at the University of Southern Denmark.

In another finding, the team reported that the silver nose piece Brahe famously wore after losing part of his own nose in a duel was not actually silver. Though the prosthesis has not been found, greenish stains around the nasal area of Brahe's corpse contained traces of copper and zinc, indicating that his fake nose was made of brass, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When we exhumed the body in 2010, we took a small bone sample from the nose so that we could examine its chemical composition," project leader Jens Vellev, an archaeologist at Aarhus University in Denmark, said in a statement. "Surprisingly, our analyses revealed that the prosthesis was not made of precious metals, as was previously supposed ... So Tycho Brahe's famous 'silver nose' wasn't made of silver after all."

The team also performed a computed tomography (CT) scan of Brahe's skeleton, which they hope will allow them to create a reconstruction of the astronomer's face.

A film crew has been following the team throughout their investigation, and Danish broadcaster DR TV is set to air a documentary about the project on Sunday Nov. 18.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus