Worm Regeneration May Lend A Hand in Human Healing

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This Research in Action article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

About the size of toenail clippings, planarians are freshwater flatworms that can re-form from tiny slivers. This feature not only lets them repair themselves, but it lets them reproduce by breaking apart and then creating new worms.

Here are two other important features: More than half of planarian genes have parallels in people, and some of their basic physiological systems operate like ours. By studying how these features behave as the worms regenerate, scientists might move one step closer to learning how to generate or regenerate human tissue and cells, such as insulin-producing cells for people with diabetes or nerve cells for patients with spinal cord injuries.

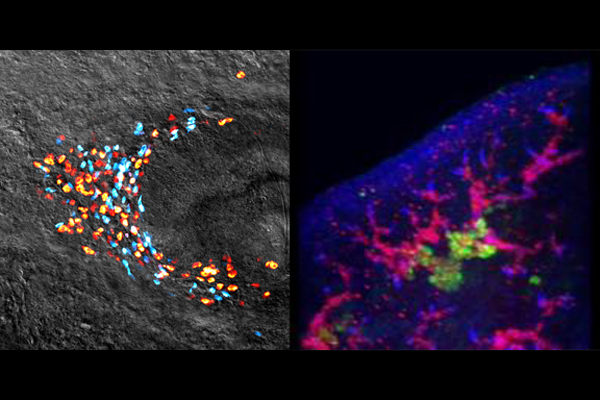

The picture on the left shows a cell colony grown from a single planarian stem cell, which, like a human embryonic stem cell, has the potential to become many different cell types. Here, the cells labeled red will create more stem cells like themselves, and the cells labeled blue will make functional flatworm tissue like muscle and skin. Scientists at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research inhibited certain planarian genes and then studied how the colonies changed.

The researchers were able to quantify the results, and, from what they learned, implicate the genes responsible for cell renewal and those spurring the creation of different cell types. They hope to use this knowledge to pinpoint parallels in mammals, perhaps one day harnessing the regenerative power of human embryonic stem cells.

The other image shows a cross-section of a flatworm. The green clusters and magenta specks throughout the planarian are specialized structures that push waste toward the animal’s bile ducts. These organs, which comprise the animal’s excretory system, are like our kidneys, in that the structures are lined with cells and the ducts employ comparable filtration methods. One key difference, though, is that flatworms can regenerate their excretory systems from next to nothing.

To better understand how this regeneration happens, researchers at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research removed the heads from planarians and watched as the creatures regrew the missing body part, including tubular structures of the excretory system. Among other findings, they learned that interfering with the expression of one gene kept the tubules and pores from branching off a precursor structure and from re-forming. This suggests the gene plays a critical role in regeneration. Studying similar genes in mammals could shed light on how we maintain our kidneys — and might grow new ones.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. To see more images and videos of basic biomedical research in action, visit NIH's Biomedical Beat Cool Image Gallery.

Editor's Note: Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Research in Action archive.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus