Disintegrating Alien Planet Has Comet-Like Tail

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

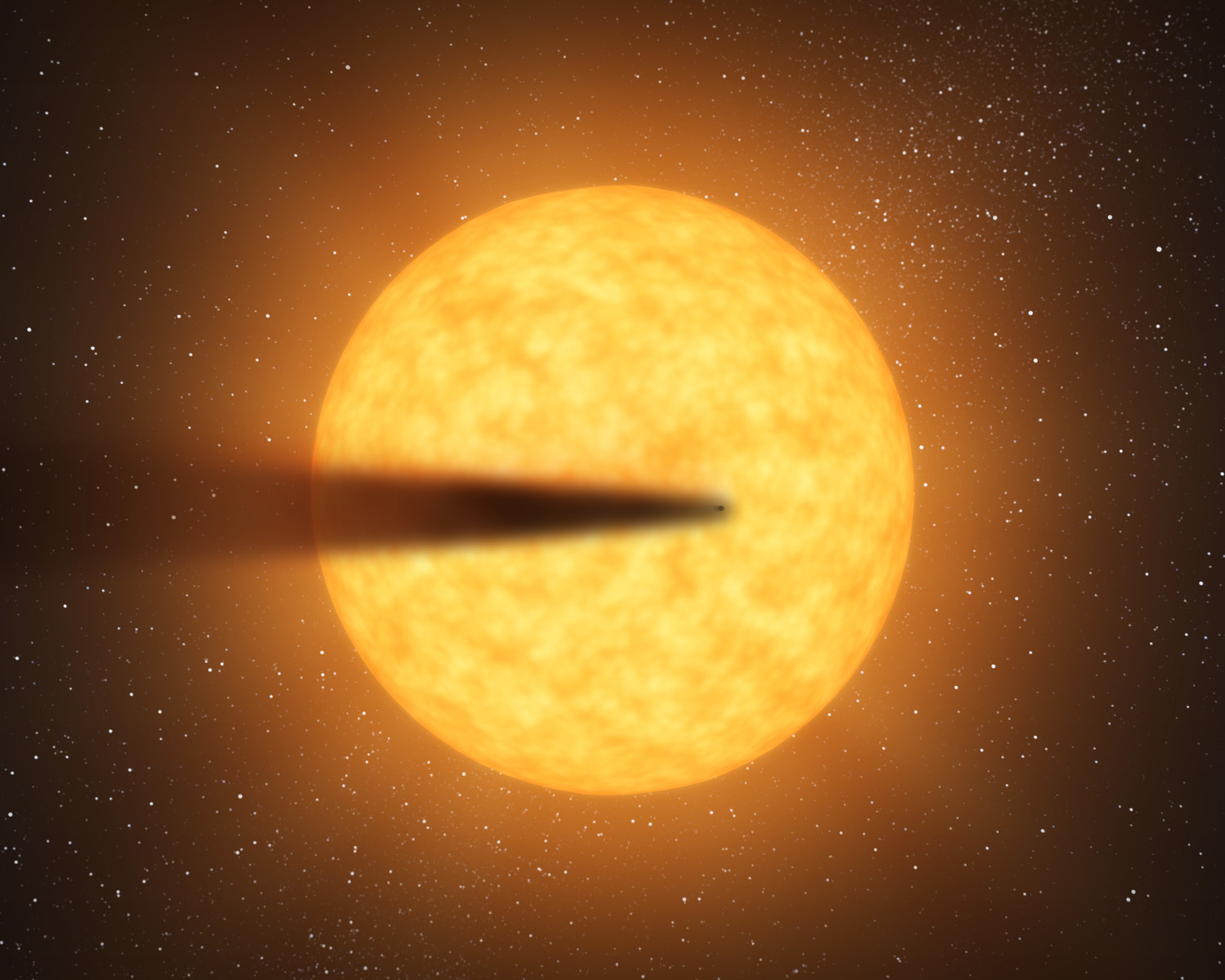

Astronomers have found a dusty tail streaming off a faraway alien planet, suggesting that the tiny, scorching-hot world is indeed falling apart.

In May, researchers announced the detection of a possibly distintegrating exoplanet, a roughly Mercury-size world being boiled away by the intense heat of its parent star. Now, a different team has found strong evidence in support of the find — a massive dust cloud shed by the planet, similar to the tail of a comet.

Both studies used observations from NASA's Kepler space telescope, which spots alien planets by flagging the telltale brightness dips caused when they pass in front of their parent stars from the instrument's perspective.

The unfortunate alien planet lies about 1,500 light-years away from Earth. It sits very close to its host star — completing an orbit every 15 hours — and is therefore incredibly hot, with surface temperatures estimated to be around 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit (1,982 degrees Celsius).

The discovery team noticed that light from the planet's star, which is called KIC 12557548, dims in oddly variable ways uncharacteristic of other planet-hosting stars. The researchers hypothesized that the brightness dips are caused by a somewhat amorphous, shape-shifting body, and they predicted that the planet is likely surrounded by a huge veil of dust and gas. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

In the new study, a different team of scientists affirms the existence of this planetary dust tail. Looking closely at Kepler's data, they found clear signals that KIC 12557548's light is being scattered and absorbed by large amounts of dust.

"Some of this dust escapes into space, where the intense stellar radiation quickly evaporates it," study lead author Matteo Brogi, of Leiden University in the Netherlands, said in a statement. "The variable amount of dust leads to the observed variability in the star's dimming."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Further work with different instruments could help nail down just what the planet is made of, researchers said.

"By observing the dust clouds in different colors, something Kepler cannot do, we will be able to determine the amount and the composition of the dust and estimate its lifetime," said co-author Christoph Keller, also of Leiden University. "As the evaporation peels the planet like an onion, we can now see what used to be the inside of a planet."

The study has been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

The $600 million Kepler space telescope launched in March 2009. Since then, it has detected more than 2,300 potential alien planets, 77 of which have been confirmed to date. Kepler scientists have estimated that at least 80 percent of the instrument's finds will end up being the real deal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus