Diet Season: Dinosaurs Slim Down in New Analysis

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Dinosaurs have shed some extra pounds just in time for beach season, with a new analysis suggesting the mighty sauropod previously known as Brachiosaurus weighed tens of tons less than earlier estimates.

Artists' renderings of dinosaurs have long been plagued by discrepancies, with some depictions larger and heftier than others.

"The whole point is we were trying to get around the guesswork" of artistic reconstructions, study researcher Bill Sellers, of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, told LiveScience. The researchers found that among the artists, "the ones reconstructing their dinosaurs as quite skinny are more right."

Skinny skeletons

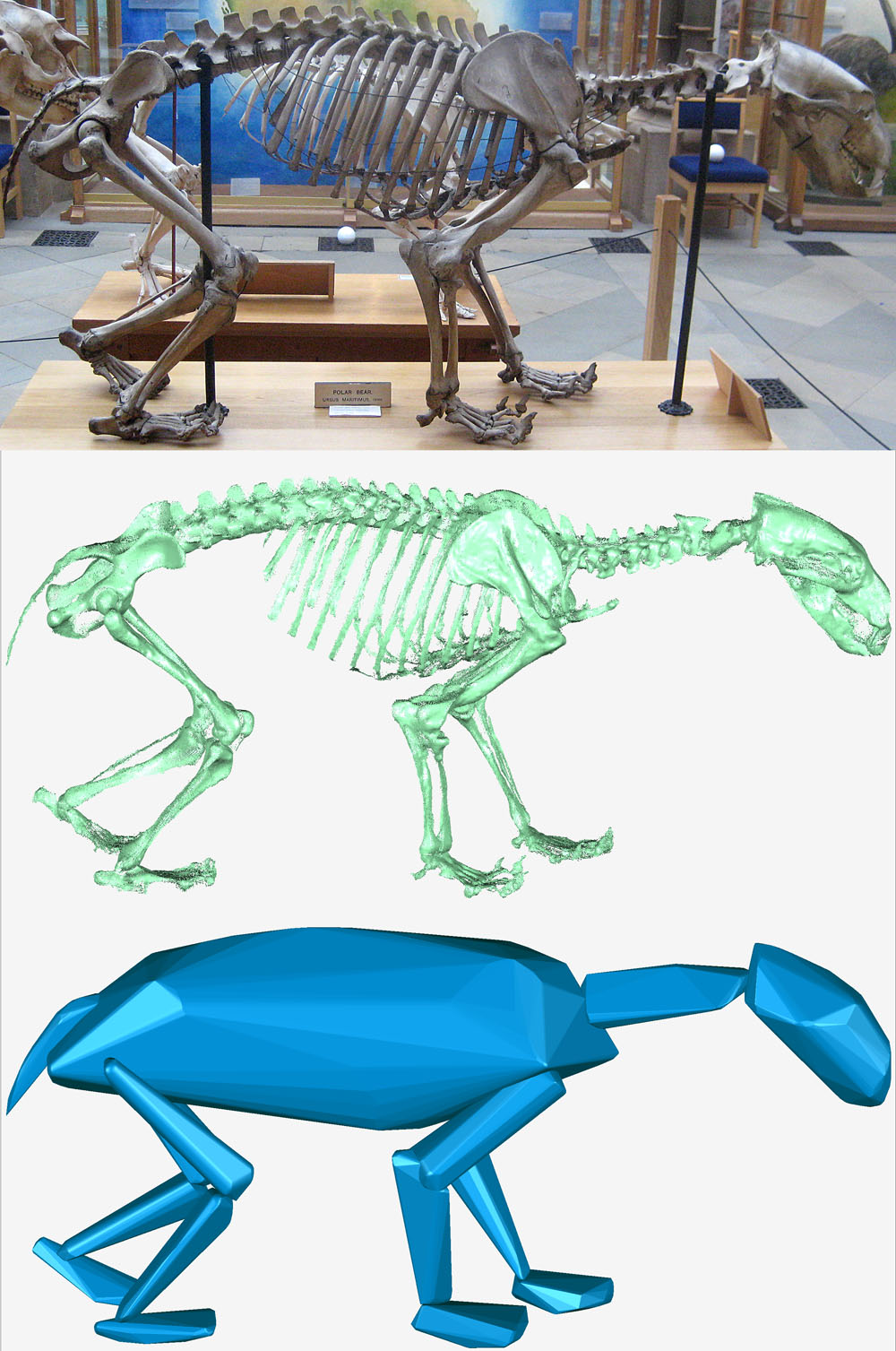

To come up with their skinny dinosaur suggestion, the researchers analyzed the skeletons of living species and compared the skeletal sizes with those animals' actual weight. Using 3D images made by laser scans of full sets of bones from 14 large mammals, including a polar bear, giraffe and elephant, the researchers calculated the "minimum wrapping volume" needed to cover a skeleton with flesh.

"All we can do when we are looking at these long-dead fossil animals is rely on what we can find out from living animals," Sellers explained. They chose these large mammals instead of the dinosaur's closest relative, the crocodile, as comparison points because they are land-adapted. (Crocodiles are adapted to living in the water, where body mass is less of an obstacle.)

Using the relationship between skeletal bones and amount of skin and fat needed, the researchers came up with a mathematical equation that also could be applied to dinosaurs. By using a computer to calculate mass, the researchers said, they took subjectivity out of the equation. In fact, when the researchers based their body-size estimates on artists' skeleton-informed reconstructions of dinosaurs, there were large discrepancies in the estimated weight. [Album: Colorful Dinosaur Art]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They would take a scan, then produce an artistic reconstruction of the scan," Sellers said. "No two people would get exactly the same answers. Some would make them fat dinosaurs, and some would reconstruct them as skinny dinosaurs."

Bony Brachiosaurus

Comparing the number that came out of their mathematical analysis with what science actually knows about the living species they chose, the researchers saw that that the weights were reliably about 20 percent more than the minimum volume. If this also held true for dinosaurs, such as the large dinosaur known as Brachiosaurus (now called Giraffatitan brancai), the researchers said, many have overestimated the beast's weight.

The researchers then used the same laser-scan technique on the Berlin Brachiosaurus, a nearly complete skeleton of the large sauropod. When they calculated the wrapping volume and added 20 percent, they found the big dinosaur came in at around 25 tons (almost 23 tonnes; a ton is 2,000 pounds and a tonne is 1,000 kilograms).

This weight is a lot less than historical estimates, which average about 34.7 tons (31.5 tonnes) and ranged up to 88 tons (80 tonnes).

The new analysis comes closer to more modern estimates of the sauropod's weight at 18 tons (16 tonnes) from a report in the Journal of Zoology in 2009.

The study is detailed in the June 6 issue of the journal Biology Letters.

Follow Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus