Scientists Should 'Cool It' on Alien Life Claims, Biologist Says

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists and the media need to stop "crying wolf" about new life forms, says a prominent molecular biologist.

Writing in the open-access journal PLoS ONE, Scripps Research Institute scientist Gerald Joyce said that frenzies such as the one over alleged arsenic-eating bacteria in 2010 could ultimately lead to lack of interest in the kind of science it would take to discover new life forms, should they exist.

"I just worry that we cry wolf too many times, and people are going to start tuning it out," Joyce told LiveScience.

"Let's just cool it on these false alarms," he added.

New life

False alarms over new life forms have ranged from the arsenic bacteria kerfuffle ? in which scientists announced they had found bacteria that could incorporate arsenic rather than the usual phosphorous into their DNA ? to synthetic biology, such as molecular biologist J. Craig Venter's transplant of a synthetic genome into a living cell.

Though both studies represent important work, Joyce said, neither qualifies as new life. The arsenic bacteria fit firmly into the known tree of life, and their arsenic-eating abilities are still under scrutiny. Venter's synthetic genome required an already living cell to function and was glued together from pre-existing DNA snippets. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

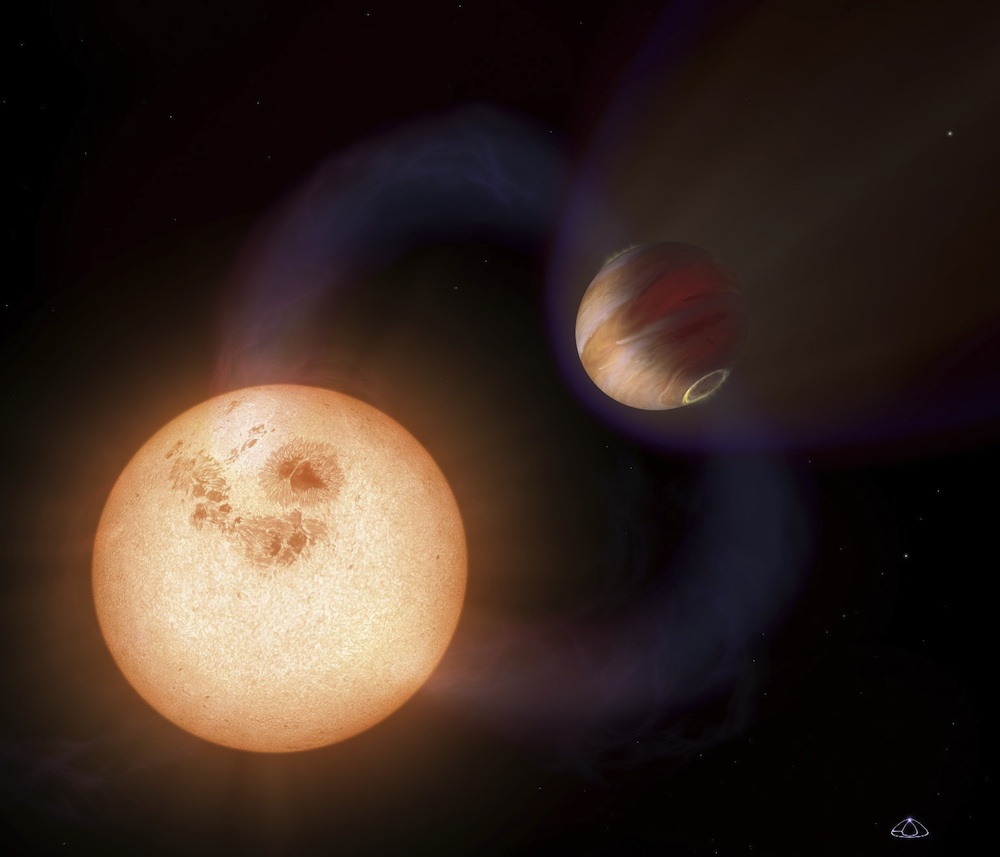

With the increasing discovery of planets in "habitable zones" orbiting far-off stars, Joyce expects more claims of potential extraterrestrial life to add to hype about new life forms on Earth. In fact, he said, the idea that there is surely life on more than one of so many habitable planets out there is based on nothing more than wishful thinking. As it is, scientists have no idea what the probability of life might be or what it would take to get a new life form started, Joyce said.

What is life?

In his essay and accompanying podcast, Joyce calls for a sober look at the possibility of new life forms. Biology is "chemistry with its own history," he said, meaning that life is simply a chemical process capable of holding a molecular memory that evolves over generations. These memories are like "bits" of information stored in a computer, Joyce said, and all known life is part of the same system here on Earth.

With only one system to look at, researchers can't statistically infer the likelihood that life arose elsewhere in the universe, too, Joyce said. There's no way to know whether we're one of many or one of a kind, or whether life arises easily or only in extraordinarily rare cases.

"We can take pure chemicals in a test tube and stack the deck like crazy to try to get something replicating and evolving, and that hasn't happened yet," Joyce said. "Right now the jury's out on whether it's hard or easy."

If or when scientists do find extraterrestrial life or create synthetic life in the lab, they'll have more information on which to base the likelihood of other unique life out there in the universe, Joyce said. For now, he said, researchers should "hunker down" and avoid the temptation to overhype the possibility of new life forms.

"To me, it's something kind of fundamental about human loneliness," Joyce said. "We just wish it to be, so that we're not alone."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus