Night-Blind Mice Gain Vision

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

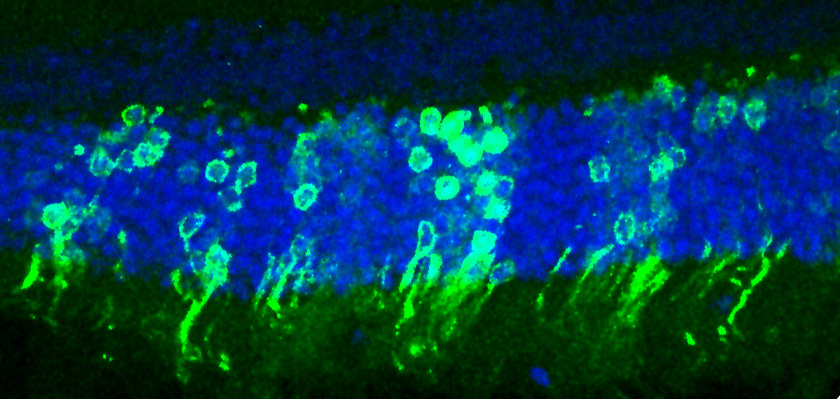

Some night-blind mice can now see in low light, thanks to a new procedure. The mice gained night vision after immature light-detecting cells were injected into their eyes.

The researchers have a long way to go before their technique can be considered for humans, but they are excited that the cells were able not only to survive and integrate with the mice's native eye cells, but also to forge connections to the brain. These connections allowed the light-detecting cells to send signals into the parts of the brain that turn electrical impulses into vision.

"We show this can result in functional connections and improvement in vision," said study researcher Robin Ali of the University College London. The model they used was for night blindness, but treatments to replace light-detecting cells in the eyes could help people with many different types of blindness, including advanced macular degeneration.

Ali noted that this was just one step toward developing treatments to replace light-detecting cells in human eyes. "This is a really important proof of concept, but it's not at a stage we can immediately move to a clinical trial. There are other steps that we need to take," he told LiveScience.

This procedure, if proven in further testing including human trials, could help those who suffer from blindness caused by malfunctioning light-detecting, or photoreceptor, cells called rods and cones. Rod cells detect low levels of light; cone cells are worse at detecting light but can detect fine details and color. These two types of cells line the back of the eyeball and tell the brain when they detect light. The brain then interprets these signals to form images.

Normal mice have between 3 million and 4 million rod cells. In the study, Ali and his colleagues tested their transplantation method in mice that didn't have any rod cells and couldn't see in low light. The researchers implanted about 200,000 rod cells that they had isolated from the eyes of healthy young mice. They waited for the cells to implant into the mice's eyes and then did several tests to see if they were working. The treated mice reacted to low-light visual stimuli; the researchers could even see newly implanted rod cells send signals to the brain when stimulated.

The main test, though, came in the dark. Before treatment, the researchers had trained the night-blind mice on a task in the light, in which they had to find a hidden platform by a visual cue at one end of a Y-shaped pool. In bright light the mice could see the visual cue and swim for the platform, but in the dark their sight was so bad they ended up swimming in circles.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After nine mice received transplanted rod cells, four were able to see the visual cue even in the dark and swam straight for it. They were the four mice in which more than 25,000 of the transplanted rod cells had survived and integrated into their eyes. The other five mice had lower levels of rod cells, and didn't perform well on the task, meaning there is a minimum number of rod cells needed to see in low light.

In the future, the researchers hope to use either human adult (harvested from the patient) or embryonic stem cells, which they've turned into rod cells, instead of the cells from living mice. They currently are testing the similarities between lab-made and mouse-made rod cells.

"We are able to make photoreceptor cells [rods and cones] from stem cells. We are now seeing whether we can transplant those," Ali said."That's an important step for clinical application."

This study was published today ( April 18) in the journal Nature.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus