Why Woodpeckers Don't Get Concussions

For woodpeckers, "thick skull" is no insult. In fact, new research shows that a strong skull saves these birds from serious brain injury.

Woodpeckers' head-pounding pecking against trees and telephone poles subjects them to enormous forces — they can easily slam their beaks against wood with a force 1,000 times that of gravity. (In comparison, Air Force tests in the 1950s pegged the maximum survivable g-force for a human at around 46 times that of gravity, though race-car drivers have reportedly survived crashes of over 100 G's.)

Researchers had previously figured out that thick neck muscles diffuse the blow, and a third inner eyelid prevents the birds' eyeballs from popping out. Now, scientists from Beihang University in Beijing and the Wuhan University of Technology have taken a closer look at the thick bone that cushions a woodpecker's brain. By comparing specimens of great spotted woodpeckers (Dendrocopos major) with the similarly sized Mongolian skylark, the researchers learned that adaptations in the most minute structure of the woodpecker bones give the skull its super strength.

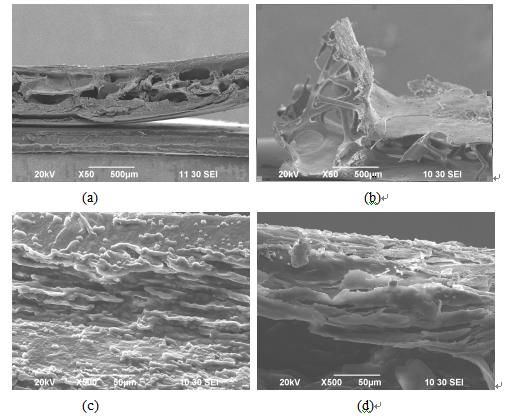

Notably, the woodpecker's brain is surrounded by thick, platelike spongy bone. At a microscopic level, woodpeckers have a large number of trabeculae, tiny beamlike projections of bone that form the mineral "mesh" that makes up this spongy bone plate. These trabeculae are also closer together than they are in the skylark skull, suggesting this microstructure acts as armor protecting the brain.

The woodpecker's beak does not differ much from the lark's in strength, but it contains many microscopic rod structures and thinner trabeculae. It's possible that the beak is adapted to deform during pecking, absorbing the impact instead of transferring it toward the brain, the researchers report in the journal Science China Life Sciences.

The findings could be important for preventing brain injuries in humans. Each year, more than 1 million people in the United States alone sustain and survive a traumatic brain injury, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Another 50,000 people die of their injuries. Understanding the microstructures of the woodpecker's skull could help scientists develop better protective headgear for sports and dangerous work, the researchers wrote.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescienceand on Facebook.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.