Future Sea-Level Rise Foreshadowed in 3-Million-Year-Old Rocks

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

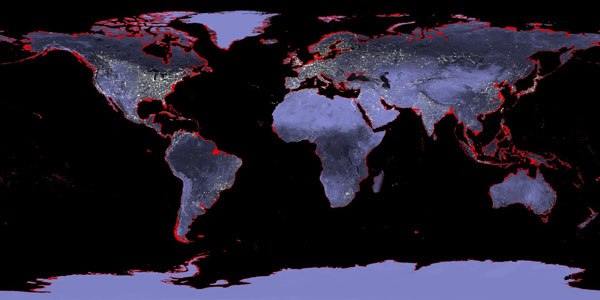

About three million years ago — at a time when climate conditions paralleled those of modern times — sea levels stood about 66 feet (20 meters) higher, indicates new research.

The height of ancient sea level indicates Greenland and the western part of Antarctica had no ice sheets, and the massive ice sheet covering East Antarctica, the "big elephant in the room", had also contributed, according to lead study researcher Kenneth Miller, a professor at Rutgers University.

For decades, there has been controversy around what it takes to melt the East Antarctic Ice Sheet — which contains about 7.2 million cubic miles(30 million cubic kilometers) of ice, according to the British Antarctic Survey. This new research indicates that, about 3 million years ago, some melting of this ice sheet had occurred.

"Understanding howfast and how much the East Antarctic Ice Sheet can melt is really what we have learned most from our study," Miller said, adding that the results indicate certain parts this ice sheet are more vulnerable than was thought.

The estimate of 66 feet (20 meters) is important because melting the ice now on Greenland would raise sea levels 26.2 feet (8 meters), melting the West Antarctic Ice Sheet raise it another 5 meters (16.4 feet). Since together these don't account for the difference, water that is now frozen on the East Antarctic must have been liquid 3 million years ago.

In this case, the past has relevance for the future. During the Pliocene Epoch, the status of sea levels 2.7 million to 3.2 million years ago, average global sea-surface temperatures at the time have been estimated to be about 3.6 to 5.2 degrees Fahrenheit (2 to 3 degrees Celsius) warmer than today. In addition, atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide —the dominant greenhouse gas —at the time appear comparable to those measured in 2011.

During annual climate talks, international climate negotiators have set an unofficial goal of cutting global greenhouse gas emissions to a level that would limit global temperature increase this century to 3.6 degrees F (2 degrees C), although scientists believe this cap looks increasingly unachievable. [How 2 Degrees Will Change Earth]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Of course, sea levels won't reach Pliocene-levels overnight, or even by the end of the century, these results offer a hint at a distant future, according to Miller.

"This is telling us a lot about what is going to happen eventually, eventually meaning really more than 500 years (from now)," he said, adding that by 2100 sea levels are expected to increase by 2.6 to 3.3 feet (0.8 to 1 meter).

Miller and colleagues derived a more precise estimated of Pliocene sea levels than has been accomplished in the past by looking at sediment cores from Virginia, New Zealand and the Eniwetok Atoll in the northern Pacific Ocean. They examined the pressures on top of the sediments laid down at this time, as well as chemicals clues to environmental conditions, including ratios of oxygen isotopes (atoms of different weights). The ratio of oxygen isotopes laid down in sediment change with the volume of water locked in ice elsewhere on the planet.

Sea levels don't rise in immediately with air temperatures because water warms more slowly and ice takes time to melt. Melt water isn't the only contributor to sea level rise; water expands as it warms.

The study was published online Monday (March 19) in the journal Geology.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus