'Lost' Da Vinci Portrait, and its Origins, Stir Controversy

This article was updated Sunday, Oct. 16 at 1:37 p.m. ET

Christie's auction house may have sold a priceless piece of art by Leonardo da Vinci for a little more than $21,000, according to researchers who claim to have identified the origins of the hotly debated painting.

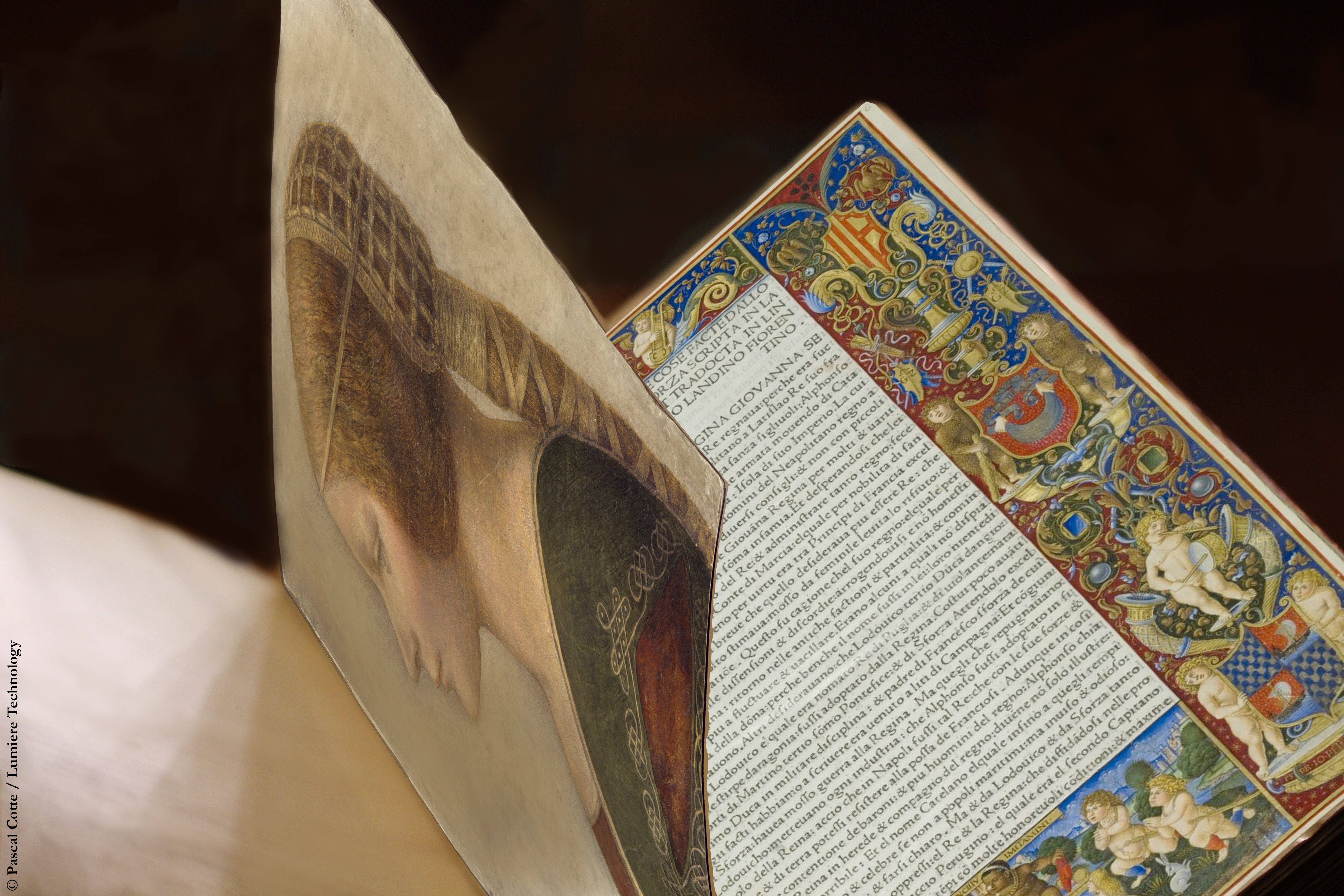

The painting appears to have come from a 500-year-old book containing the family history of the Duke of Milan. Art historian Martin Kemp, of the University of Oxford, believes the mystery painting, which appeared in 1998, is a portrait of the duke's daughter, created by da Vinci for her wedding book. [See images of the portrait and book]

"We knew it came from a book, you have the stitch holes and can see the knife cut. Finding it is a miracle in a way. I was amazed," Kemp told LiveScience. "When doing historical research on 500-year-old objects … you hardly get the circle completed in this way."

In 2010, Kemp first suggested that da Vinci painted the portrait, and since then, art historians have debated over both its origin and the painter. In fact, several art historians contacted by LiveScience said they wouldn't comment on the piece or didn't return emails. An earlier examination of the artwork by a gallery in Vienna led the director there to say it was not a da Vinci, and they are unswayed by the new evidence.

From storage to source

The portrait was sent to Christie's in 1998, with art historians there suggesting the piece came from 19th-century German artists called the Nazarenes, who mimicked the Renaissance style. (This was disproved after carbon dating estimated the portrait's creation between 1440 and 1650.) It was titled "Head of a Young Girl in Profile to the Left in Renaissance Dress."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kemp wasn't convinced and started looking into the painting's history. He first saw the portrait as an attachment to an email in 2008, and immediately recognized da Vinci's left-handed style. He went to see it in Zurich and his co-author, Pascal Cotte, engineer and founder of art analysis start-up Lumiere Technology, examined it in Paris.

Kemp and Cotte then published "La Bella Principessa: The Story of the New Masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci," (Hodder Hb, 2010) claiming the work might be a da Vinci, a claim that many respected historians have disagreed with, some vehemently. [History's Most Overlooked Mysteries]

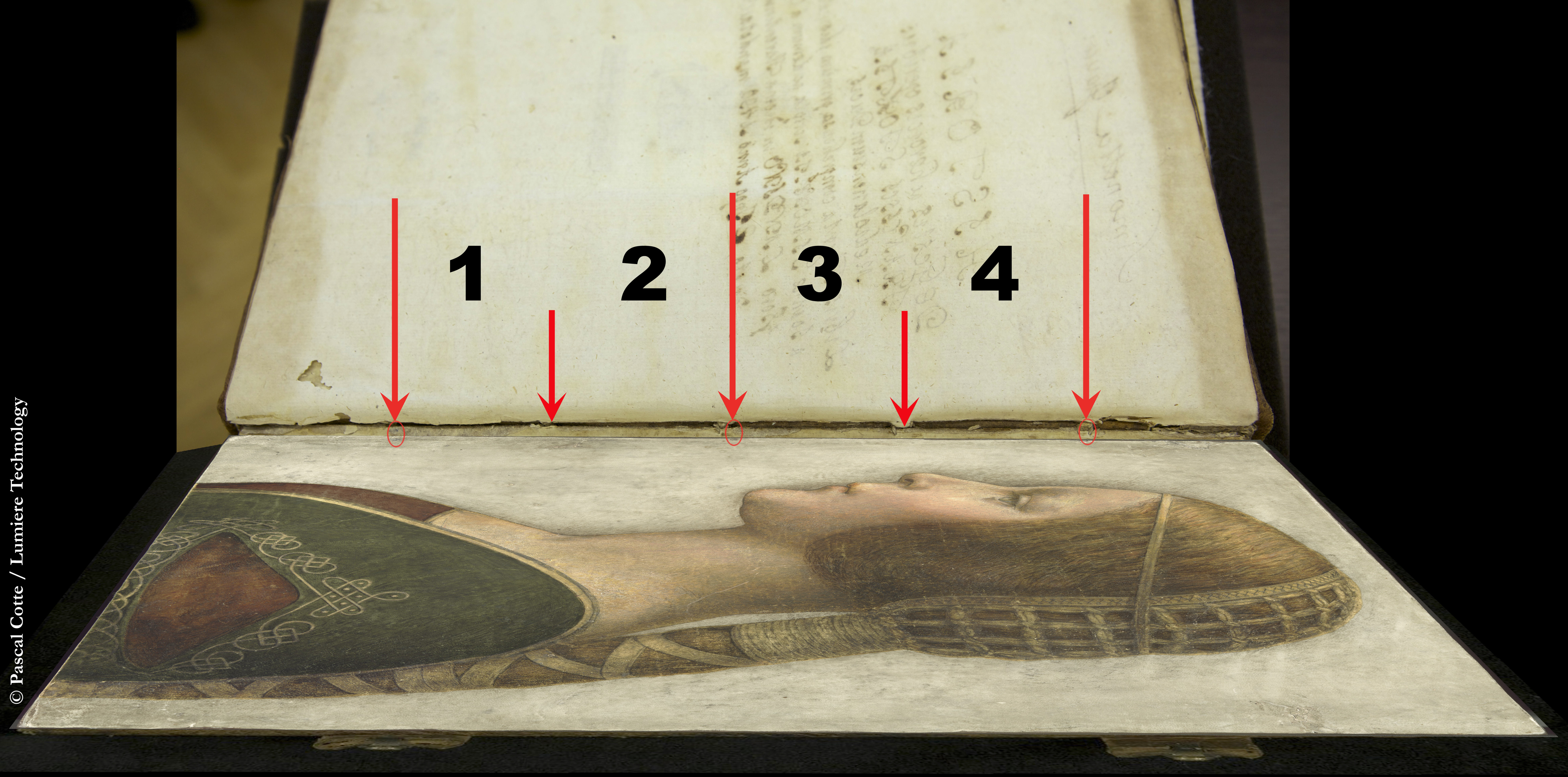

The portrait is made on vellum, a specially prepared skin normally used for writing and printing. No work by da Vinci has been found on vellum before, though it was frequently used in books. Researchers believe the portrait came from a book, because three stitch holes are visible on the portrait's left margin. It is also made of chalks and ink, not paint.

A wedding gift

"The chance of identifying the vellum book it came from was pretty small, a needle in the haystack, one would say," Kemp told LiveScience. That was, until American art historian D. R. Edward Wright of the University of South Florida, suggested that Kemp look at a set of books titled the "Sforziad."

There were at most four copies made, Kemp said. Aside from the copy in the National Library in Warsaw, there is a copy in London and one in Paris. Each book was custom-made and had different art and cover pages; evidence that this portrait had been "ripped" out was only found in the Warsaw book. The image was probably removed during the 18th century when the book was rebound, Kemp said.

Da Vinci was an artist in the duke's residence for several years between 1481 and 1499. He was the only left-handed artist in the court at that time, the researchers said.

Matching page to book

Upon examination, Kemp saw that the stitch holes from the page match up with the stitching on the book, but they aren't the only evidence Kemp puts forward. Because vellum is made from processed skins, each sheet has different qualities. The thickness and composition of this sheet matches up perfectly with the vellum from the book, Kemp said. There are also cut marks on the edge of the book.

"It was apparent from the evidence we got about the vellum and the missing sheets, within reasonable margins of doubt, that's where it comes from," Kemp said. "At 500 years old, you never have as much confirmation as you like, but this is as good as it gets."

Kemp and Cotte have published a short version of their examination of the book and the portrait's cut marks and binding, along with their analysis of the vellum online. The painting has been renamed "La Bella Principessa," though its true origins are still debated.

Still up for debate?

The Albertina art gallery in Vienna decided not to exhibit the drawing, because when examined by their institution, "no one is convinced that it is a Leonardo," art gallery director Klaus Albrecht Schröder told ArtNEWS.

LiveScience asked spokesperson Verena Dahlitz what the gallery thought of the new data; she replied in an email, "We still believe that it is not an authentic drawing by Leonardo." When asked who could have painted it, if it had come from the Sforziad, she said: "We think that the drawing is from the 19th century."

Art blogger Hasan Niyazi, on his blog The Three Pipe Problem, updated his article on the La Bella Principessa controversy in reaction to Kemp's find, writing that, in his opinion, "Critics of the piece must now re-orient their approach — an argument that it is by a Leonardo contemporary may still arise from some. Although any allegation that it is a later piece is less likely to stand up against the body of evidence amassing for this work."

Many of the historians contacted by LiveScience refused to comment on the piece. William Wallace, an art historian at Washington University in St. Louis wouldn't comment on the piece, but said: "I think because few, like me, wish to pronounce on an unlikely attribution, especially without having seen the original," Wallace told LiveScience in an email. "Egos are easily bruised in a small field, and Kemp, after all, is a well-respected scholar."

Kemp will be publishing his findings in an updated edition of his book, "Leonardo" (Oxford University Press, 2011). A grant from National Geographic funded his search for the book, and the network will be producing a documentary on the search for the portrait's true origins to air in early 2012.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to reflect the full professional name of D. R. Edward Wright.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.