Gigantic Birds Trod Earth During Age of Dinosaurs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

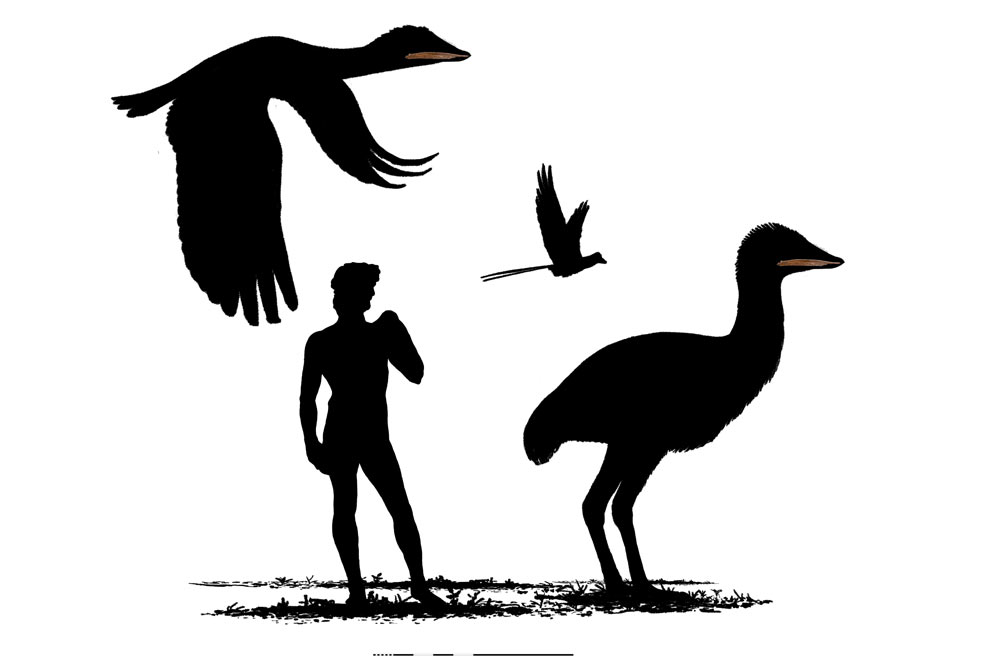

An enormous bird, taller than an adult human, walked the Earth (and maybe flew above it) more than 80 million years ago, according a newly discovered fossilized jaw. The finding suggests oversize birds were more common during the Age of Dinosaurs than scientists thought.

Scientists have long known that birds, or avian dinosaurs, lived during the Mesozoic, the era when dinosaurs ruled the Earth. Although researchers have discovered numerous Mesozoic bird species, these were virtually all the size of crows or smaller.

The ostrich-size Gargantuavis philoinos, was known from France, dating back from the Late Cretaceous near the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. However, it was uncertain whether or not it was the lone exception among its puny relatives. Now another has popped up in Central Asia, revealing giant birds were no flukes.

"Big birds were living alongside Cretaceous non-avian dinosaurs," researcher Darren Naish, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Portsmouth in England, told LiveScience. "In fact, these big birds fit into the idea that the Cretaceous wasn't a 'non-avian-dinosaurs-only theme park' — sure, non-avian dinosaurs were important and big in ecological terms, but there was at least some 'space' for other land animals."

Naish added, "Badger-sized mammals, big, diverse land-living crocs and, we now know, really big birds all lived alongside non-avian dinosaurs in parts of the Cretaceous world." He and his colleagues named the bird Samrukia nessovi — "Samrukia" after the samruk, the mythological Kazakh phoenix, and "nessovi" after Russian paleontologist Lev Nessov.

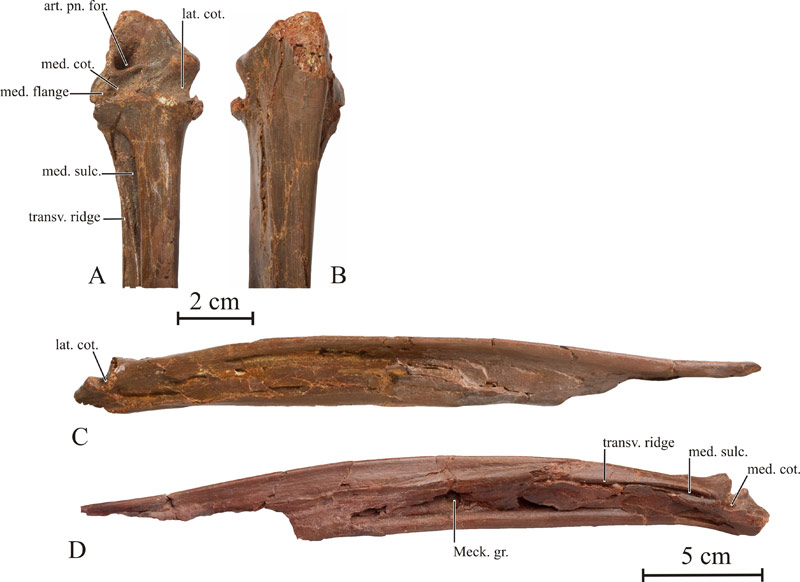

The toothless lower jaw came from a dry, hot, hilly site in Kazakhstan, though when this creature was alive — about 80 million to 83 million years ago — the area was a floodplain crisscrossed by big meandering rivers.

The size of the fossil suggests the bird's skull was about 12 inches (30 centimeters) long.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

There is no way to tell from the fossil's structure or thickness whether the bird could fly. Based on its estimated size, the researchers calculate that if the creature was flightless, it probably stood 6 to 10 feet (1.8 to 3 meters) tall, about as big as its counterpart Gargantuavis philoinos; if it flew, it probably had a more than 13-foot (4 meter) wingspan. [Album: The World's Biggest Beasts]

"We can now be really confident that Mesozoic terrestrial birds weren't all thrush-sized or crow-sized animals — giant size definitely evolved in these animals, and giant forms were living in at least two distinct regions," Naish said. "This fits into a larger, emerging picture — Mesozoic birds were ecologically diverse, with lots of overlap between them and modern groups."

The area has yielded a diverse assemblage of other fossils, and "Samrukia was conceivably in danger from tyrannosaurs, dromaeosaurs and other predatory dinosaurs of the region," Naish said. Other creatures in the area included armored dinosaurs, duckbilled dinosaurs, other birds, turtles, salamanders and freshwater and brackish-water sharks.

It remains uncertain whether Samrukia was predatory, herbivorous or omnivorous. "The lower jaws don't reveal any obvious specializations for, say, dedicated plant-eating, or feeding on aquatic prey — if I had to guess, I'd say it was a generalist, but this is just a guess," Naish said. "The main thing we can hope for is new material that will provide more information on this bird — it would be great to know what role they were playing in these Cretaceous ecosystems."

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Aug. 10) in the journal Biology Letters.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus