Climate Change Understanding Falls Along Political Lines

While public opinion on climate change might be polarized, it's a stark contrast to the scientific community's unified stance regarding the warming of our planet. The latest research finds public understanding of the issue falls along political party lines, with Republicans most often saying Earth's climate is either not changing or agreeing it is changing -- but that those changes are due to natural causes.

Democrats, on the other hand, most often agreed that the climate is changing now due mainly to human activities. The research is published in a report put out by the University of New Hampshire's Carsey Institute and announced this week.

"Although there remains active discussion among scientists on many details about the pace and effects of climate change, no leading science organization disagrees that human activities are now changing the Earth's climate," said study researcher Lawrence Hamilton, professor of sociology and senior fellow with the Carsey Institute. "The strong scientific agreement on this point contrasts with the partisan disagreement seen on all of our surveys."

The reason may have to do with where we get our information on climate change, which Hamilton suggests is not scientists, but instead through news media, political activists, friends and other nonscience sources.

"People increasingly choose news sources that match their own views. Moreover, they tend to selectively absorb information even from this biased flow, fitting it into their pre-existing beliefs," Hamilton said. (For instance, a study published in 2009 in the journal Communications Research showed that college students chose news sources that matched their views on abortion and gun ownership issues.)

Another survey of American and Australian participants published this year showed that the weather affected acceptance of manmade global warming. The weather-warming link may be the result of global warming and climate being such complex and long-term trends. That would make it more likely for people to grasp onto a simpler, more easily accessible explanation -- the weather.

In the new study, Hamilton and colleagues gathered their data from surveys conducted in 2010 and early 2011 asking nearly 9,500 individuals in seven regions in the United States about climate change. The three climate change questions included:

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- How much would you say you understand about global warming or climate change?

- Which statement is more accurate? Most scientists agree that climate change is happening now, caused mainly by (human activities/natural causes).

- Which of the following statements do you personally believe? Climate change is happening now, caused mainly by (human activities/natural forces).

Overall, most respondents said they understand either a moderate amount or a great deal about the issue of global warming or climate change. And though many participants agreed that climate change is happening now, they were split on whether this is attributed mainly to human or natural causes.

For the political split, the greatest difference between Democrats and Republicans was found for those who were most confident of their climate change knowledge.

For instance, out of the Olympia Peninsula respondents who said they had a moderate or great understanding of climate change, just 19 percent of Republicans said they personally believe that warming is due to human activities; that's compared with 78 percent of Democrats who said the same. Among those who said they have little or no understanding, the gap narrowed to 23 percent versus 52 percent of Republicans and Democrats, respectively, who said they believe climate change is caused by human actions.

The take-home for all those involved: "There are things scientists could do better to communicate, using the new media; and journalists could do better if they gained science literacy," Hamilton told LiveScience. "But such improvements would still be arrayed against a political climate that rewards wedge-issue polarization."

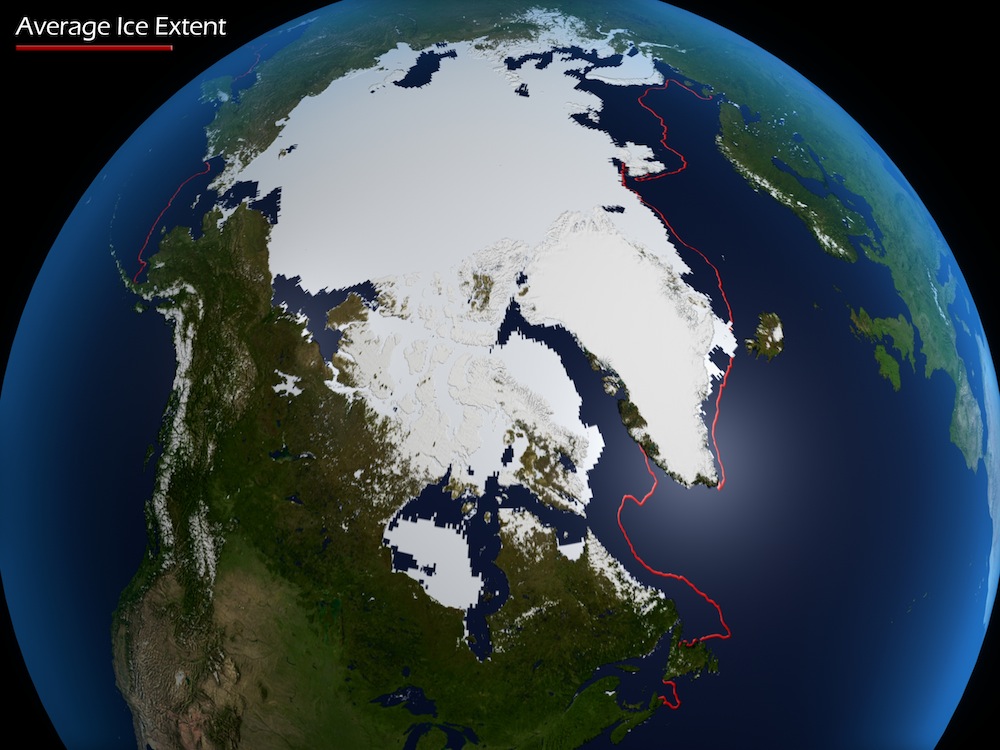

Perhaps in the future, global warming will have its say, though. "As the environment changes, visible realities such as Arctic ice or extreme weather events might eventually play a larger role in public perceptions," Hamilton said.

The research was supported by grants from the Ford Foundation, Kellogg Foundation, Neil and Louise Tillotson Fund, New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, Office of Rural Development in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, UNH Sustainability Academy and the Carsey Institute.

You can follow LiveScience Managing Editor Jeanna Bryner on Twitter @jeannabryner. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus