New Way to Look at Old Paintings: Have X-Rays, Will Travel

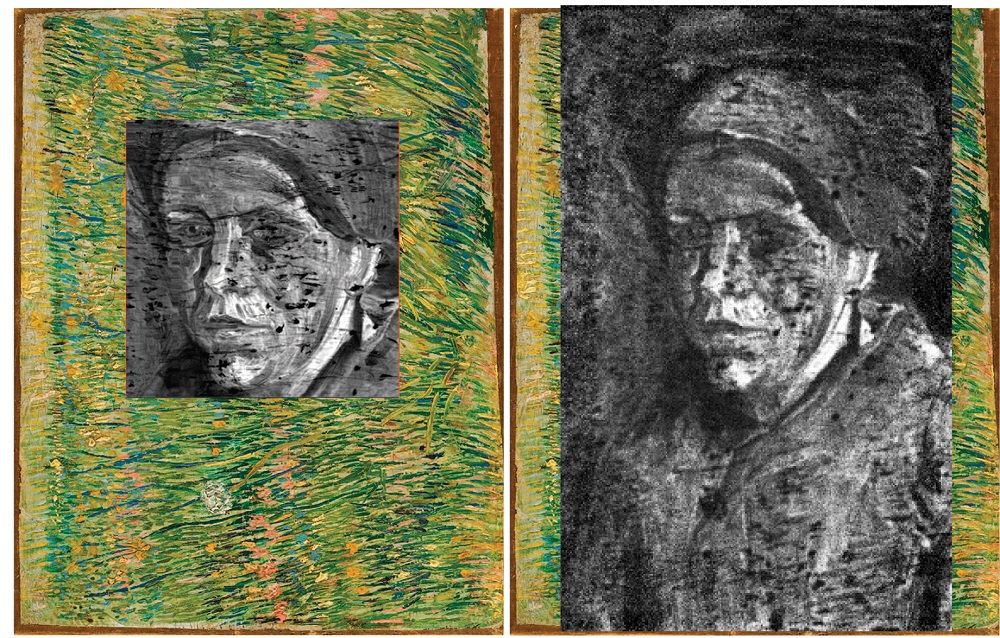

A technique for peering under the surface of classic paintings came with a risk: The old, precious artwork had to be removed and transported through changing environments to the machine that would bombard it with X-rays.

A new mobile scanning device is sparing art lovers from a potential heart attack by allowing scientists to examine a painting right where it hangs. The new scanner already has led to surprising revelations about how the Old Masters went about their work, scientists announced yesterday (March 29) at the American Chemical Society meeting in Anaheim, Calif.

Finding long-hidden layers and changes made to the art is like watching over the artist's shoulder as he paints, said study author Matthias Alfeld, of the University of Antwerp in Belgium. "It says something about the history of the painting and about the surrounding of the artist when he worked," Alfeld told LiveScience.

The technique is called scanning macro X-ray fluorescence analysis. Alfeld and his colleagues used it on more than 20 paintings from the 16th through the 19th centuries, including works by Rembrandt, Caravaggio and Rubens.

X-ray examination

The X-rays, which don’t harm the artwork, can analyze the pigments used, which is valuable in deciding how to store or restore a painting. Different materials in the paints absorb and expel different X-rays when bombarded. The scan can also help experts determine whether a painting is genuine or a copy.

The technique is not new, but until now the paintings had to be carefully transported to a particle accelerator, and some paintings were too large to scan. The mobile instrument can be used at the museum site, so the painting doesn't have to be exposed to changes in humidity or be jostled when moved. Large or awkward paintings also can be scanned.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The XRF technique also can see better than methods such as infra-red reflectography, which can decipher between outer paint layers but is limited in how far it can penetrate by how thick the layers are and what the paint is composed of.

Unveiling under paintings

The process gives researchers a look at the "underpainting" layers, which include the first shading layers that the artists build up on, and at any change the artist makes after the fact.

While artists commonly created an underpainting to define features of the final painting, the researchers discovered that Rembrandt, in one painting, used an odd mix of pigments — probably the scrapings from his palette — to apply the priming and shading layer. "This first sketch of light and darkness — it was known from unfinished paintings that it exists, but didn't know about its presence in finished paintings," Alfeld said.

Several of the scanned paintings showed evidence of changes made by the artist after the undepainting – a process called pentimenti, from the Italian pentirsi, meaning "to repent." "The underpaintings are different than the ones that are finally shown. This [scanning technique] can link this underpainting to Rembrandt's workshop and can tell us what happened to this painting before it was finished," Alfeld said.

Such information can be used to disperse or confirm doubts about a painting's authenticity.

The American Chemical Society is hearing several presentations on how chemistry can be applied to artwork. Details and analysis of the mobile X-ray set-up was published in the Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry March 21.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus

![Different elements in each of the pigments show up diffeerently when bombarded with X-rays. cobalt (Co [mislabeled as Cu] - in blue pigments), mercury (Hg - in the pigment vermillion), antimony (Sb - yellow pigmentation) and lead (Pb - used in white pigments) shown in the painting "Pauline in a white dress in front of a summery tree scenery" and suggests that the hair once had ribbons painted into it.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/F3RD8wsbhGqjbL3ZxcajCC.jpg)