Abortion Debate: Little Evidence Sonograms Change Minds, Doctors Say

Editor's note: As of August 4, 2022, pre-Roe abortion bans can be enforced in Texas, although this doesn't allow prosecutors to bring criminal charges against providers. A trigger law that bans abortion will take affect in two months. This is following the Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade on June 24, 2022, thus eliminating the constitutional right to abortion in the U.S. The following article was published on Feb 16, 2011, and therefore the legal information is no longer accurate.

—Abortion laws by state: https://reproductiverights.org/maps/abortion-laws-by-state/

—For questions about legal rights and self-managed abortion: www.reprolegalhelpline.org

—To find an abortion clinic in the US: www.ineedanA.com

—Miscarriage & Abortion Hotline operated by doctors who can offer expert medical advice: Available online or at 833-246-2632

—To find practical support accessing abortion: www.apiarycollective.org

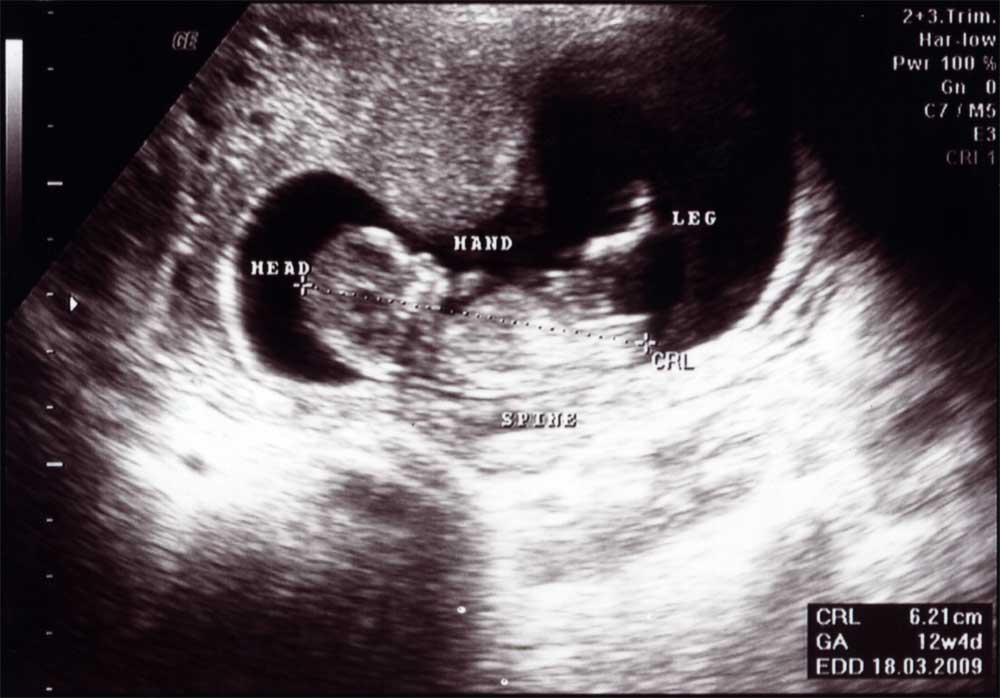

The author of a proposed law in Texas that would require doctors to perform sonograms on women seeking abortions has called the bill "empowering" to women, saying it could help some change their minds about going through with the procedure. But reproductive rights researchers and abortion providers say there's little scientific evidence that the law will change women's minds.

Texas Senate Bill 16, also known as the "sonogram bill," was passed by a state Senate committee last week and could come up on the Senate floor as early as Thursday (Feb. 17), according to a spokesperson for bill author and state Sen. Dan Patrick (R-Houston). If passed, the law would require that doctors perform the ultrasound while describing the embryo or fetus. Women could avert their eyes from the image, but it is not clear if they could choose not to hear the description. Doctors would also be required to "make audible" the fetal heartbeat, if present, though the women could choose not to hear it.

"It is my belief that some women will choose alternatives to abortion when they are armed with all the facts about their unborn baby," Patrick wrote in a Feb. 12 op-ed defending the bill in the Houston Chronicle.

Sonograms and the abortion debate

Fetal sonogram bills aren't a new front in the abortion wars: Eighteen states have laws on the books either requiring a woman to receive information on ultrasound services or requiring they undergo an ultrasound before an abortion. Underpinning the debate for supporters is the assumption that women will be encouraged to keep the pregnancy after viewing the image.

"If 20 percent [of women seeking abortions] change their minds after seeing a sonogram, that's 15,000 to 20,000 lives saved," Patrick told Houston news station KHOU last week.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Abortion providers say numbers like that don't match their experiences.

"I've never seen anybody who said they were coming in to an abortion, wanted to see the ultrasound, reacted to it and then changed their mind on the basis of that," said Ellen Wiebe, an abortion provider and director of the Willow Women's Clinic in British Columbia, Canada.

Wiebe has done some of the few studies worldwide that attempt to look at women's reactions to viewing an ultrasound pre-abortion. The research can't speak directly to laws like the proposed Texas bill, Wiebe told LiveScience, because in that study "nobody was ever forced to do something they didn't want to do." But it is the closest thing to research anyone has ever done on state sonogram policies.

The study, published in 2009 in the European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, found that, when given the option, 72 percent of women chose to view the sonogram image. Of those, 86 percent said it was a positive experience. None changed their mind about the abortion.

In another study, this one published in 2009 in the journal Contraception, Wiebe analyzed how many women chose to look at the embryonic or fetal tissue removed during an abortion. Only about 28 percent of women were interested – "they're curious," Wiebe said – but of those, 83 percent said that viewing the embryo or fetus did not make the process more emotionally difficult.

Testimony and data

Despite the growing number of states with abortion-related sonogram laws, it's difficult to get reliable data on how the policies affect the abortion rate, said Rachel Jones, a senior research associate with the Guttmacher Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to researching sexual and reproductive health. Researchers who have tried to look into the effects of 24- or 48-hour waiting periods have found that abortion rates might drop in those states, she said, but increase in neighboring states as women go where the law is less restrictive.

The political sensitivity surrounding abortion has also stymied research in the past. In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention barred its scientists from publishing in a special edition of the journal The Lancet about abortion.

A spokesperson for Patrick's office acknowledged the lack of data on the effects of ultrasound viewing, but said the proposed law was based on "quite a bit of testimony here in the state regarding women's experiences."

Pre-abortion ultrasounds are already the standard of care in reproductive clinics, said Sarah Wheat, a spokesperson for Planned Parenthood of the Texas Capital Region. She said in the three clinics in that region, about a third of clients choose to view the images. Patients are also given information and printed materials explaining the abortion procedure, she said. Texas law mandates that patients receive a state health department booklet about abortion at least 24 hours before the procedure.

(In the U.S., the most common abortion procedure is a surgical one in which a suction is used to aspirate the embryo (between six and 10 weeks) or fetus (after 10 weeks) from the womb. The aspiration procedure can be performed up to 16 weeks after the woman's last period, though 90 percent of U.S. abortions happen within the first 12 weeks. After 16 weeks, abortions are usually performed using the dilation and evacuation, or D&E, method, in which the entrance to the womb is expanded and suction or medical instruments are used to remove the fetus. About 17 percent of abortions involve drugs that force a miscarriage in the first nine weeks of pregnancy.)

Medical ethics

For some doctors, the debate comes down to medical ethics. Legislators without medical backgrounds are forcing their way into the doctor-patient relationships, said Matthew Romberg, a private-practice ob-gyn in Round Rock, Tex., who testified against the bill in front of the Senate committee.

Romberg does not provide what are commonly thought of as "elective" terminations; his patients are women with wanted pregnancies who discover that the fetus has chromosomal abnormalities or physical deformities not compatible with survival. The bill ignores that each situation is unique and prescribes a cookie-cutter script for doctors, Romberg said.

"The last thing I need to be told from a Texas senator whose background is in, you know, talk radio, is how to perform my sonogram or how to choose my words," Romberg told LiveScience. (Patrick hosts a daily AM talk show in Houston.)

Romberg said he believes the bill will pass into law before the legislative session is over. Texas Gov. Rick Perry has designated the bill as "emergency" legislation, a fast-track procedure used to speed bills through the legislative process. About 80,000 abortions take place in Texas each year, according to Guttmacher Institute data. Should the law pass, it is unlikely to change that number, according to researchers contacted by LiveScience.

"Most women have made up their minds to have the abortion before they've even called the facility to make the appointment," said the Guttmacher Institute's Jones. "Laws like this, all they do is just… inconvenience women and inconvenience providers."

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.