Parasite's Virus Packs a Disease-Causing Punch

Viruses are usually bad for those they infect. But not for one parasite, which gets a competitive boost from carrying a virus, new research is showing.

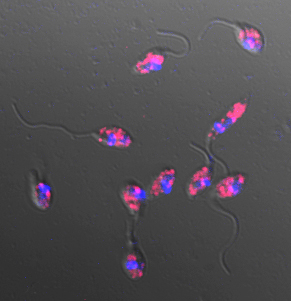

The virus, called Leishmania RNA virus-1 (or LRV-1), infects parasitic protozoa, or single-celled organisms, of the genus Leishmania, which causes skin sores. When humans are infected by virus-carrying Leishmania, the virus activates the inflammation system, causing a much more virulent disease with big, destructive sores that can make it hard to eat and breathe.

"For the parasite, there is an advantage to having the virus," it only takes fewer virus-infected parasites to cause a lesion, lead author Nicolas Fasel, of the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, said. "It's the first description where a virus increased the virulence in the pathogenecity of a parasite."

This virulent type of disease is called mucocutaneous leishmania, and is most prevalent in South America. There are two other types of the disease that people can get, including a milder form of skin sores (cutaneous) or a dangerous whole-body infection that includes fever, anemia and organ swelling (visceral).

The disease comes from the subgenus Leishmania viannia, which can cause all three types of leishmania. The infection starts with the bite of a third parasite, the sand fly, which injects the immature parasite into its human host. These parasites infect the host's white blood cells and mature, where they kill the macrophage (the white blood cells) and can be sucked up from the bloodstream by another sand fly, where they reproduce and can infect others.

Leishmania infection, called leishmaniasis, affects about 12 million people worldwide, and is a major health problem in the Mediterranean, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Central and South America.

The researchers were particularly interested in mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, a particularly harmful form of the disease that destroys the soft tissues of the nose and mouth. This type of infection tends to be caused by the parasite Leishmania Viannia. They wanted to figure out why the mucocutaneous infections are much more virulent and are localized to South America. Only about 5 to 10 percent of the 12 million people infected with Leishmania get the mucocutaneous form of the disease.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We knew there was a virus in these species, but nobody understood the role of this virus," Fasel told LiveScience. "People looked but nobody found it; they did not have the tools to do it like we have now."

Manipulating macrophages

Once inside a human, the infected protozoa makes its way into the immune system's macrophages, which normally gobble up invaders like viruses . Inside little compartments within the white blood cells, the protozoa get shuttled to the warm, wet and cozy mucous membranes that line parts of our bodies.

The researchers ran tests on hamsters and mice with strains of L. viannia, showing that only some viannia strains spread rapidly and cause high levels of damage similar to that seen in mucocutaneous leishmaniasis.

In subsequent experiments, the team discovered that the rapid, highly damaging form of the infection was linked to a protein called TLR3 found in the tiny compartment of the macrophages where the protozoa (parasite) live.

When Fasel infected mice that don't have this TLR3 receptor with virus-ridden parasites, they didn't develop the mucocutaneous version of the disease. The receptor-virus interaction is the key to the pathogen's virulence, he said, but how this interaction increases the pathogenicity, they aren't sure.

"TLR3 normally helps the immune system fight infections, but when we deleted it in mice and repeated the experiment, infections with virus-infected Leishmania were less harmful," Fasel said.

New therapies

The results have direct implications for public health, researchers say.

"So far, different clinical outcomes in infected humans have mostly been claimed to result from different genetic backgrounds of the individuals," Christian Bogden, a researcher from Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany who wasnot involved in the study, said in an e-mail.

Bogden notes that there is still much work to be done on the relationship between the virus, parasite and host, but thinks the explanation is a good one. "This is an exciting study which for the first time provides a clear-cut explanation of why different strains of a Leishmania (Viannia) species can lead to differential courses of infection in humans," he told LiveScience.

There are a few drugs available to treat Leishmania, though researchers aren't sure how they work, and people's immune systems are already becoming resistant to the drugs, especially in South America. Vaccines are also in the works, but none are currently in trials.

Knowing how this virus regulates the parasite's virulence could help researchers develop new therapies to modulate the severity of this disease. Slowing down the body's inflammatory response could slow the progress of the disease, and increase the effectiveness of current drugs.

Fasel says that screening for this virus in the field could help determine correct treatment pathways for Leishmania infections, especially if they are at high risk for developing this mucocutaneous version of the disease. He is in the process of starting a clinical trial in Colombia to determine if this screening is helpful.

"There could be a link between inflammation and resistance," Fasel said. "We need to test in the field if by controlling inflammation, people respond better to the treatment."

The study appears today (Feb. 11) in the journal Science.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.